Part One

Till Hell Freezes OverThe twins suspected it was alive, but they weren’t exactly sure if it was plant or animal.

Edith, white-haired and older by seventeen minutes, went to find a flashlight while Kat, blond with white roots, knelt to take a closer look. A small phosphorescent organism, about as bright and arresting as a firefly’s glow, bloomed in the seam of the hall closet. It almost looked as if someone had chewed a piece of iridescence and stuck it, like gum, on the wall. But it wasn’t inanimate like gum; its surface was roiling as if something beneath were struggling to be born. Kat tried to call Edith back to be assured that she wasn’t imagining things, but Kat was struck dumb. A swell rose out of the glow until the head of whatever was fighting to get born pushed through, a fleshy bud, about the size of a newborn’s thumb. Kat gasped. Her breath must have disturbed the new life, or awakened it, because a puff of spores sprayed out, luminous and ephemeral as glitter. The closet housed their mother’s archives, the original letters from her advice column, the earliest dating back to the nineteen fifties, when Consultations with Dr. Mimi was first syndicated. All they needed was for spores to land on one of the file boxes and start feasting on the invaluable old papers inside.

Edith shined the flashlight over Kat’s shoulder. They could now see clearly that it wasn’t a plant or an animal. It was some kind of mushroom, a fleshy speckled stalk capped by a deeply oxygenated pink head. Edith gasped. They sounded identical.

“Where did it come from?” Edith’s voice quavered between stubborn disbelief and reverent horror. “How does a mushroom just start growing out of a wall, or is it growing through the wall? Oh my god, what’s behind it? You shouldn’t be so close, Kat. It may be poisonous.” She kept the light trained on it, as if the mushroom were under interrogation.

They decided not to touch anything until they spoke to someone with expertise in these matters. But who would that be? Who do you call? The Health Department, Pest Control, the EPA, the CDC, the Fire Department? Should they call the super?

But they both knew what Frank would do—nothing. He’d gawk at the mushroom, sympathize, light a cigarette, even though Edith asked him not to smoke around the archive, and then call their landlady, Vida Cebu. Vida was an actress who had bought the building last year, a narrow, three-story, neoclassic row house on Berry Street in Brooklyn. She had restored the warren of dwellings above Edith’s apartment into a private house again, but she could do nothing about the parlor floor. Edith had inherited their mother’s rent-controlled lease—a tenant till death. And now Kat had moved in. Edith paid two hundred dollars and twelve cents a month.

While Kat peeked over Edith’s shoulder, Edith typed mushrooms, brooklyn into her computer’s search engine, but the only listings were gourmet stores selling truffles and porcinis.

“Isn’t a mushroom a type of mold?” Kat asked.

Big Apple Mold, Terminix, Mold Be Gone, Ecology Exterminating Service, Basement RX, Empire Disaster Restoration. Who would have guessed there were so many mold specialists in their zip code? After the tenth answering machine, the twins realized that everybody was closed for the weekend. It was two o’clock, Sunday afternoon. Edith dialed the only one with an after-hours number.

“Mold Be Gone,” a woman answered.

“Thank god someone’s there. We found a mushroom growing in our closet. What should we do?”

“I only work for the answering service, but I’d pour bleach on it and keep your air conditioner on high. Someone will call you Monday.”

The window units were already running at full tilt, and had been since the heat wave began twenty-six days ago. The temperature had broken last year’s record by two degrees. People were fainting in the streets.

The first thing the twins did was rescue their mother’s archives. Sixteen heavy boxes weren’t easy to move.

“It’s grown, hasn’t it?” Edith said breathlessly, staring back into the empty closet.

The mushroom now stood upright and had tripled in size.

Bleach might not kill it, but surely it would stunt its growth. Edith found a Clorox bottle under the kitchen sink, Kat rubber gloves in the bathroom. Before uncapping the bleach, they tied handkerchiefs around their noses and mouths. The fumes immediately saturated the tight space. Eyes smarting, Edith tipped the bottle’s spout directly over the mushroom while Kat held a large tin foil roasting pan underneath to catch the runoff. When the first drops hit, the mushroom must have sensed its fate. Its gills shrank closed. Edith kept pouring. The thick stalk started going flaccid. The pink head lost its blush. She finished the bottle. The roasting pan was now a tub of bleach. Kat set it on the floor, under the obviously dying mushroom.

They watched its demise with profound relief. The more it withered and shriveled, the calmer they became. It shrank even faster than it had grown. Finally, it just hung by a tendril.

“I’m going to pull it off,” Kat said.

“Don’t touch it. I’ll get a knife,” Edith said.

The blade barely scratched the skin before the mushroom fell into the roasting pan.

They inspected the corner. The wall looked surprisingly clean, except for a pale spore print in the seam, but even that seemed superficial. They scraped it away with the point of the knife. The mushroom had only been stuck, not rooted, to the wall.

They scrubbed the area three separate times, with bleach, with rubbing alcohol, with antibacterial dish soap, and finally, Edith sprayed Raid on it. Before cleaning up, Edith turned off the lights in the hall closet and shut herself inside to hunt for any luminous pinpricks of overlooked spores. Satisfied they’d eradicated all they could find, she and Kat carried out the roasting pan and dumped its contents in the gutter, including the now shriveled twist of fungus.

They returned to the apartment. The closet had never looked so clean. It almost seemed as if they’d imagined the mushroom.

“That was disturbing,” Edith said. “My god, it grew freakishly fast. The head was so pink and bulbous. It almost looked like a giant’s thumb had poked through the wall.”

Kat waited to see if Edith would draw the obvious analogy, but she wasn’t sure if her white-haired, sixty-four-year-old sister had ever seen an erect penis. She suspected Edith was a virgin. The not knowing was an inscrutable power Edith held over her. All their lives, Kat had told Edith the most intimate details about her lovers and escapades, whereas Edith confided nothing to her. All Kat knew was that Edith, before retiring, had worked in one of those anthill corporate law firms as the head librarian and lived with their mother until she died. Had Edith had a secret lover, perhaps one of the married partners? Surely Edith had been in love once or twice? Had she ever been caressed? Kissed? When they were children, Edith and Kat looked identical. But by their early twenties, you could barely tell they were twins. Edith was stout, Kat voluptuous. Edith kept her original brown hair color; Kat changed hers as often as she fell in love. It wasn’t just the physical differences. Their identical countenances expressed two very different souls. Edith wore their features sensibly and wisely; Kat gave them sparkle and animation. But these days, sharing the same clothes, the same meals, they again looked identical. Or did they? Kat had only seen her sister naked once since she’d moved in two months ago, when she had to help Edith bathe after a bad bout of flu. Edith’s skin looked almost translucent compared to her own freckled, sun-damaged hide, but otherwise they’d aged with remarkable similarity. Sponging her likeness, all Kat could think was that this was what she would have looked like had she never allowed herself to live and be loved.

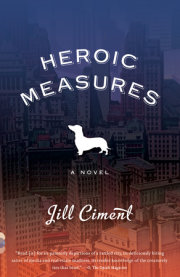

Copyright © 2015 by Jill Ciment. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.