I’ve suddenly realised that every one of my visits to St John’s began and ended with The Narrows.

This channel, no wider than a shout, linked the harbour to the sea. The gap through which it passed was like a crack in a sky full of granite. As fissures go, it was simply mesmerising. The whole city faced it, as if watching a door ajar. Out there was weather, the Old World, shades of darkness and ice. In here, life had a more turquoise texture, and smelt of potatoes and fresh-cut pine. As a natural portal, it had defined the beginning and end of journeys for centuries. These were the most easterly rocks of the Americas and the beginning — or end — of the New World. The French, when Newfoundland was briefly theirs, had called it

Le Goulet — The Throat — a name that was nicely sinister and functionally perfect. From its place in the hills, St John’s watched, waiting to see who’d sail in next.

I often found myself plodding round the harbour, responding to some primordial urge to be uphill, up in the rocks. First, I would climb through The Batteries, several layers of Victorian artillery; Inner, Outer, Middle, Upper, Lower. These old dug-outs had long been colonised by eccentrics, people living in driftwood cottages and flotsam. I always imagined that their proximity to the wild, gnashing sea had left them a little distracted. Their homes dangled over the black froth and they themselves were given to some curly pronouncements:

‘Inteligence not Educasion!’ said a sign, or

‘CANADA = NEWFOUNDLAND’S NEWEST COLONY’

Every now and then — and most dramatically in 1959 — the walls of The Narrows crumbled, crushed these dwellings and swept them out to sea. When that happened, the Battery people reacted as all Newfoundlanders did in times of wrecked homes; they simply went out into the woods and cut themselves new ones.

As I climbed higher, the broader picture emerged. St John’s just about filled the foreground. Although I would become very fond of this city of planks and ship’s paint, it told terrible lies about its age and size. It was not, as it claimed, the oldest city in North America (for that was to overlook — among others — Mexico City) nor had its population ever reached much beyond 100,000. But it behaved like a capital and, from up here, I could see two cathedrals, a Supreme Court and a miniature government.

Beyond St John’s, I fancied that I could see into the heart of the island. This was, of course, an absurd thought; Newfoundland is the size of Ohio or England. All I was looking at were the soggy hinterlands — the barrens — where Johnsmen went on week-ends for boil-ups, gunning and perhaps a little grassing.

If I turned and faced the other way, up the great gulley, I could see the draggers running for home, each beneath a helix of seabirds. In winter, the horizon would be speckled with ice and, in summer, a crease of brilliant blue. Had I been here on 9th July 1882 — on the cusp of Spring — I might have spotted the

Albert. She was picking her way through the last knobs of ice, Grenfell on the fore-deck, troubled by the smell of burning.

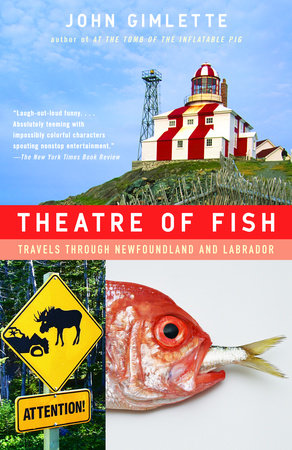

Copyright © 2005 by John Gimlette. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.