I took advantage of the break to edge my way into the crowd. The carnival bands had completely taken over every meter of the square. As had previously been announced, the most renowned ones from the South East were there. The musicians and dancers seemed to be camped out for the moment amidst their sleeping instruments: different types of drums, bamboo horns, conch shells, rattles, saxophones, flutes, cones, accordions. Here and there, under the trees, while eating and drinking, the Jacmelians began to tell stories.Rene Depestre, Hadriana dans tous mes reves

Jacmel 2001"Carnival Country"

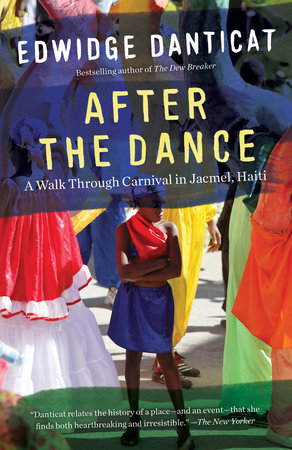

During carnival Jacmel is not a town or a city. It is a country," Michelet Divers, Jacmel's best-known carnival expert, tells me over a tall glass of lemonade on the airy terrace of the Hotel de la Place, a three-story, white Victorian-style restaurant, bar, souvenir shop, and hotel in the Bel-Air section of Jacmel. The terrace has an eye-level view of a flamboyant-filled piazza, where young men straddle the low colonnaded walls to watch the bustling human and automobile traffic stream by.

I am here for my first national carnival. Since 1992, Divers explains, Jacmel has been hosting two carnivals on consecutive weekends, the national one, which draws people from all over Haiti and the Haitian diaspora, and the local one, which is primarily attended by the residents of Jacmel.

Everyone I have spoken to about my intention to attend the national carnival festivities this coming Sunday has recommended that I first speak to Divers. A stocky forty-seven-year-old with dark, wide-rimmed glasses, Divers is a radio commentator and former school principal. He is quick to point out that he is not the one who came up with the idea of temporary sovereignty for Jacmel, but that other Jacmelians would like to see the image of the southern coastal town of ten thousand, the Riviera of Haiti, the Ibiza of the Caribbean--as the Haitian tourist guides say--detached from the one that outsiders have of the rest of the country, particularly the capital, Port-au-Prince: dirt-poor, politically troubled, and certainly lacking any celebrations.

"Jacmel is not like that," says Divers, "especially during carnival."

A Jacmelian "by birth and choice," Divers has written a book about the Jacmel carnivals (Le Carnaval Jacmelien) and this year is the cultural adviser for both. This means that he, along with other members of the carnival committee, gets to decide which musical bands, costumed groups, individuals, and animals will be allotted a coveted spot in Sunday's colorful street parade.

I do not mention it to Divers, but this is the first time that I will be an active reveler at carnival in Haiti. I am worried that such an admission would appear strange to someone for whom carnival is one of life's passions. A Haitian writer (me)--even one who'd left the country twenty years before, at age twelve--who has never been to carnival in her own country? I imagine him asking. What was that about?

As a child living in Haiti with my Baptist minister uncle and his wife, while my parents settled in as new immigrants in New York City, I had never been allowed to "join the carnival," as the Haitian-American rapper Wyclef Jean urged many to do in his 1997 Carnival album. I was too young (under twelve), small for my age, and we lived in one of the poorest neighborhoods in the capital, coincidentally--and in much contrast to this area of Jacmel--also called Bel-Air. Long pre-Lent days of unbridled dancing, with clammy bodies pressed either against each other or within a few inches of the giant wheels of flatbed trucks serving as floats, were considered not safe for me. However, since I had as intense a desire to join the carnival as some peculiar American children have of joining the circus, my uncle for years spun frightening tales around it to keep me away.

People always hurt themselves during carnival, he said, and it was their fault, for gyrating with so much abandon that they would dislocate their hips and shoulders and lose their voices while singing too loudly. People went deaf, he said, from the clamor of immense speakers blasting live music from the floats to the viewing stands and the surrounding neighborhoods. Not only could one be punched, stabbed, pummeled, or shot during carnival, either by random hotheads or by willful villains who were taking advantage of their anonymity in a crowd of thousands to settle old scores, but young girls could be freely fondled, squeezed like sponges by dirty old, and not so old, men. Or they could be forced to participate in a maryaj pou dis, a "ten-cent or ten-minute marriage," that is, acting as if they were wed while simulating sex with a total stranger. And while we were in the realm of dangerous liaisons, there was also the possibility that a person who appeared quite normal and attractive during carnival was not a human being at all, but a demon. Besides, for the first twelve years of my life, Haiti was ruled by the dictatorship of Francois "Papa Doc" Duvalier and his son Jean-Claude. A military presence at public events was imperative, which made the streets that much more hazardous. At carnival, there were always militiamen and soldiers clubbing people over the head with sticks or rifle butts.

To spare me all this, my uncle would take me and the other residents of his household on a religious retreat in the mountains of Leogane, the birthplace of my grandparents, where we would spend the carnival week helping relatives feed their livestock and work their land. Some of my relatives in the mountains were also known to sing raunchy songs and tell ribald jokes about wives who temporarily divorced their husbands and abandoned their young children so they could be free to fully enjoy carnival; however, it was my uncle's stories that kept me away from carnival celebrations in Haiti for years.

Even after I thought I had forgotten my uncle's tales, I developed a mild fear of being buried alive in too large a crowd, hyperventilating whenever I felt that a wall of people had grown so dense around me that I would not be able to leave. Later, as an adult in New York, I would faint at demonstrations, having to be carried over people's heads like a heatstroke victim at a rock concert.

Once when I was in Salvador de Bahia, Brazil, a friend talked me into jumping into a crowd of carnival revelers when the crowd was at its most impenetrable, squeezing through a narrow street in the middle of the night. I nearly got my head bashed in by a long line of military policemen who suddenly parted the multitudes with swinging batons and nightsticks in order to force a car through.

That night in Salvador, I had done my best to stay on my feet, which was the advice I had gotten before entering the crowd--drop and people will trample you--and I had landed on a sidewalk not knowing how I had gotten there, but hearing echoes of my uncle's cautionary tales throbbing in my head.

So I avoided carnival, except as a distant observer, watching videotapes sold in Haitian music stores in Brooklyn, weeks after the festivities had ended, and marveling at the revelers' ability to surrender to the sway of so many others, release themselves temporarily from personal and global concerns: the ever present economic and political worries of the country and, in the case of some of the women of Leog*ne, the shackles of matrimony and the staunch warnings of fearful relatives who wanted to keep them at home.

Now it was the same fear evoked by my uncle's stories that had drawn me to the carnival festivities in Jacmel. I was aching for a baptism by crowd here, among my own people. I wanted to confront the dual carnival demons, which I had been so carefully taught to fear: the earsplitting music and the unbridled dancing amid a large group of people, whose inhibitions were sometimes veiled by costumes and masks.

As a child with secret artistic aspirations, I was always drawn to masks. There is an image from ancient Greek theater that I have always liked, a mask with half a laughing face and half a sorrowful one. This mask has always seemed to me a representation of the country where I was born, especially during carnival. Haitians, like the ancient Greek comedians, have always balanced their tragedies with laughter, using distressing situations as the subject of satirical songs and jest. I have also always linked the French expression jeter le masque, which means to show one's true colors, to Haitian carnival, imagining carnival as one intense moment during which so many colors are shed that each person walks in the street parade with a rainbow above his or her head.

I was still wearing my own mask of distant observer with Divers, so I didn't tell him any of this. It was only later that I would even learn to verbalize it. Sitting there with him on the Hotel de la Place terrace, I could only think of queries and quizzes for him, questions about Jacmel in general and carnival in particular.

Only a few feet from Jacmel's city hall and municipal library, the Hotel de la Place serves as a gathering spot for travelers as well as locals. It is one of many such localities around town where people sit on a terrace to talk, have a drink, and watch the street. On the walls inside are pictures of locally known natives, artists, politicians, and writers, the most quoted of which is the moon-faced and bald-headed Professor Jean Claude, who is best known for having written that there are only two great cities in the world: Paris and Jacmel. Around the bar are also photographs of the city before the many storms and fires that have forced it to be modified and rebuilt over the years. The Hotel de la Place, and the terrace where Divers and I are sitting, was once part of a family-run boardinghouse called the Pension Craft, before it burned down in the 1990s and was rebuilt as a hotel.

Divers chose the Hotel de la Place terrace for our meeting because he's waiting to be called to nearby city hall for a carnival-preparation session.

From the terrace, Divers turns his face to the street to respond to nods and hellos from passersby as he tells me, "In reality, the carnival in Jacmel begins the first Sunday in January and ends on Mardi Gras, the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday. That is officially the length of the carnival season, and during that time, Jacmel is carnival country. Every Sunday during the carnival season, people come out in costume, individually or in groups. However, the national carnival, which you will see on Sunday, is a summary of all of that. Yes, it is a parade, an exposition, but it is also a way for Jacmel to tell its story. Every costume, every mask portrays a part of our story and concerns."

"How many people are you expecting on Sunday?" I ask.

"Last year we had over twenty thousand," he says.

Divers has traveled to Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic to give lectures and to host presentations and demonstrations of Jacmel's carnival. While he is trying to recall a future date for a conference abroad, he is interrupted by a passerby who wishes to ask him a question.

"Will the mule with the tennis shoes be part of Sunday's parade?" an old man wants to know.

Divers assures the concerned reveler that yes, the mule will indeed be present. There had been a small dispute when the carnival committee and the mayor's office, which gives a stipend to all the carnival acts based on their relative needs, tried to reduce funding for the mule. The owner of the mule protested by saying, "People must think it's easy getting those kid-sized sneakers on four hoofs."

Imagining the labor alone, Divers laughs, he encouraged the carnival committee to keep the mule's funding the same.

Divers cannot speak about what other carnival repeaters will present out on Jacmel's main road, the Baranquilla, in a few days. He is bound to secrecy because part of the fun leading up to Sunday's parade will be guessing what the groups will come up with.

Max Power, the carnival club that was a huge hit last year with a parade of papier-mache faces of famous world figures, forcing Adolf Hitler to march side by side with Mother Teresa, Albert Einstein, Bob Marley, and Haiti's own deceased dictator Francois "Papa Doc" Duvalier, has two spots on the parade roster this year. First Max Power will repeat last year's performance with the same celebrities, and a few more yet to be named; then the members will change costumes and return with their piece de resistance, which is sure to blow everyone away. If Divers knows what Max Power's magnum opus will be, he is not telling.

"The carnival must have at least one revelation," he says, "an element of surprise."

Copyright © 2002 by Edwidge Danticat. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.