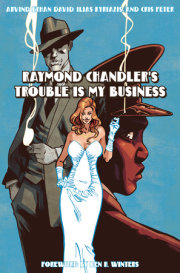

Raymond Chandler is often called the greatest of the American hard-boiled detective-story writers. His only rival would be his acquaintance Dashiell Hammett, six years his junior but finished with writing by the time Chandler, at the age of fifty, was beginning. Chandler was by heritage and education British, though he was born in Chicago in 1888, and his father was an American, a hard-drinking engineer for the railroads, whom he never saw again after his parents divorced. Without money, his Anglo-Irish Quaker mother decided to take the seven-year-old Raymond back to her home in Ireland, and then to London, where they were supported by an uncle who saw to it that he got a good English education in ‘public’, that is, private schools, most importantly Dulwich College, which also produced such other notable writers as C. S. Forester and P. G. Wodehouse. Here he became truly British, read the classics and played rugby like other English schoolboys. Though he showed an aptitude for writing, he expected to go into the law.

This was not to be. When Raymond was sixteen, the generous uncle thought he had supported his sister Florence and her son long enough. Raymond was obliged to leave Dulwich College, and so was thrust rather abruptly into a harsh real world for which he had little practical training, with the obligation to support his mother. First of all, however, he toured the Continent, like many young Englishmen before him, spending some time in Paris and in Germany to complete his education. He then returned to England to take a civil service examination, where he came in third of 800 candidates, and was given a job in the Admiralty. This did not last, nor did a term of teaching at his old school. The restless young man moved to Bloomsbury, then the heart of literary London, wrote book reviews, and tried living by his pen, not without success; but a boy of no private means needed a serious job.

When he was twenty-four, he decided to put his unpromising literary career behind him and embarked for America to make his fortune, trying a variety of jobs in a variety of places from the midwest to California, learning bookkeeping and stringing tennis rackets among others. As his biographer Tom Hiney says, ‘There is no doubt that the character of Philip Marlowe was fleshed out in these resolute, if friendless and moneyless months in Californian boarding houses.’ But it would be some years before Chandler’s great detective character Philip Marlowe saw the light of day. Chandler decided to settle permanently in Los Angeles, where he had landed a good job, and his mother came back to America to keep house for him. Unlike Dashiell Hammett, a Pinkerton detective, the more sheltered Chandler, with no real experience of crime and detection, worked as a business executive, and lived with his mother until he was over thirty-five.

The First World War was to change many things. Chandler joined the Canadian army, saying later that it felt more natural for him to wear a British uniform, and saw some action in Europe; it was in the trenches that he learned the details of blood and death that Marlowe would need to know. He was discharged in 1919 and, back in Los Angeles, planned to marry the love of his life, Cissy Pascal, a beautiful, twice-married woman seventeen years older than he, who pretended to be ten years younger than she was, and looked his own age. His mother, dying of cancer, opposed this peculiar marriage, so for a time Chandler, working as an executive in an oil company, supported both women in separate establishments. He and Cissy were married in 1924, after Florence’s death, and they would be married, happily, it appeared, until she died more than thirty years later, when she was eighty-four and Chandler sixty-six. He would live only another four chaotic, troubled years.

By the end of the 1920s, a life-long problem, alcoholism, interrupted his career. Almost all the great American writers of the twenties and thirties were alcoholics — Chandler, Hammett, Faulkner, Fitzgerald, Hemingway — and the valorization of drinking is a striking feature in the literature of the period. Hardly a page goes by without somebody taking a drink in

The Sun Also Rises and

The Big Sleep. This was almost certainly in part a result of Prohibition, which was repealed in 1933, but not before it had altered the behavior of the nation, giving it bootleggers and speakeasies, and institutionalized hypocrisy: everybody drank and law enforcement winked. Heavy use of alcohol was tolerated and even fashionable, somehow linked with the prevailing atmosphere of gaiety, wisecracking and crime. Susceptible people like Hammett and Chandler were caught in the paradox of a debilitating habit that would also furnish them with material. Another paradox: Chandler’s worsening bouts of drunkenness would get him fired from his executive job but propelled him into writing, the career he had always wanted anyhow.

The shock of being fired was salutary. Post-Depression America was in a period of self-help and individual striving. Even matchbooks advertised writing schools and vocabulary improvement techniques for people hoping to emerge from the pack. Chandler was forty-four, without a job, and with a bad drinking problem, but he had always been, and known himself to be, a good writer. After leaving school in London, he had published some poems, and it was as a poet that he saw himself, but now he signed up for a course in short-story writing. He left Los Angeles and Cissy, sobered up with the help of some army buddies in Seattle, went back to L.A. and Cissy, and learned, methodically and with great determination, how to write fiction. He studied the work of Erle Stanley Gardner, Hemingway, and the stories in a pulp magazine of detective fiction,

Black Mask, in which his first story was published at the end of 1933.

Between 1933 and 1938, when he sat down to write his first novel, Chandler had written twenty-one

Black Mask stories in which, under the guidance of its famous editor, Joseph Shaw, he polished the distinctive qualities of his later fiction. Here were the Marlowe prototypes, bad cops and good cops, Los Angeles and Bay City (Santa Monica) settings, the formula subjects of crime, sex, sadism and alcohol, a Chandleresque commitment to vivid minor characters, occasional passages of fine writing that hinted at his secret literary tastes, and a characteristic tone that hovers on the edge of satire. It is perhaps this tone that Ross Macdonald refers to when he says of Chandler that ‘he writes like a slumming angel’ — not quite the unmodified compliment it is sometimes taken for. One suspects that Chandler’s Englishness accounts for the slightly patronizing detachment in Marlowe’s tone when he describes the Los Angeles and Bay City underside, with its colorful new-world characters and rough manners. Capturing the American self-image, tough and self-deprecating, he also reflects a British impression of America, as a visitor struck by its brash color and the special cadence of the American language.

It is in

The Big Sleep that he introduces his great creation, Philip Marlowe. Marlowe is partly generic hero — the high-principled loner characteristic of both cowboy and detective genres — and partly alter-ego, embodying Chandler’s real attitudes and idealized projections of himself as a tough private detective, irresistible to women. Marlowe is an alcoholic bachelor from California, an idealistic, misogynist and generally misanthropic ex-cop who despises women and yet retains a gentlemanly, protective feeling about them. Judging from the enthusiasm of the women he meets, he’s good-looking, ‘six feet of iron man [Chandler was just under six feet], one-ninety pounds stripped and with [his] face washed’. But like the cowboy heroes of the era, he almost always turns down female advances, which have only served to confirm his low impression of the morality of women in general. He has traces of chivalry — when he has to belabor old Mrs Morrison verbally, he feels bad about it: ‘I don’t like being rough with old ladies — even if they are lying gossips.’ He goes out of his way to help Merle Davis and other nice girls. For himself, he prefers ‘smooth, shiny girls, hard-boiled and loaded with sin’, to nice girls, and most of the women he meets belong to the first category. He’s tender-hearted enough to rescue a struggling beetle, and carefully carries it out of a high-rise to place it on a bush. He gets scared, has a sense of humor and of history, and sometimes indulges himself in flowery riffs of language: ‘I’m afraid of death and despair . . . of dark water and drowned men’s faces and skulls with empty eye sockets. I’m afraid of dying, of being nothing, of not finding a man named Brunette.’

For a tough guy, he is also slightly hapless. He’s not particularly lucky, is often caught off guard, is strangled, drugged and sapped. It may be revealing that Chandler himself wanted the comic actor Cary Grant to play the part of Marlowe in the movies, though he was delighted with Humphrey Bogart too. What is appealing about Marlowe is his rueful self-questioning, his ability to say that he’s wrong or a chump. His life, lonesome and underpaid, has a dignity which he is careful to preserve. He throws Carmen Sternwood

out of his room after she’s showed up naked and called him a ‘filthy name’ when he won’t sleep with her: ‘this was the room I had to live in. It was all I had in the way of a home. In it was everything that was mine, that had any association for me, any past, anything that took the place of a family. Not much; a few books, pictures, radio, chessmen . . .’

There are obvious sources in Chandler’s own experience of several situations in

The Big Sleep. Like Carmen Sternwood, Cissy had posed in the nude when young. She had also taken opium, though hardly to the extent of the pathological Carmen. Marlowe’s alcohol problems mirrored Chandler’s own, though when writing these three novels, he was still on the wagon (he would fall off when he went to Hollywood in 1943). Not that Marlowe considers that he has a problem, though he often regrets in the morning having taken that last drink, and his lurid dreams can resemble DTs: ‘I was a pink-headed bug crawling up the side of the City Hall.’ Chandler when drinking had both blackouts and DTs, and would eventually be hospitalized for alcohol-related health and mental ailments.

The Big Sleep, greatly admired by the perceptive publisher Alfred A Knopf, who had also brought out Hammett and James M. Cain (

The Postman Always Rings Twice), was not taken seriously by critics, and sold fewer than thirteen thousand copies. People who did read it were often taken aback by the depiction of general depravity — porn pictures, dope, nymphomania, gambling, obsessions, rackets and crime rings, and the mention of unmentionables — the ‘pouched ring of pale rubber’ among the litter in a slum, for instance — though for modern readers, it is Marlowe’s coolly equable tone about all this that constitutes the novel’s charm. It would only come into its own after the film version with Humphrey Bogart appeared in 1946, though it was also published successfully in France and England.

His second novel,

Farewell, My Lovely, published in May 1940, fared little better, but Chandler had begun to develop a following, including such fellow writers as Erle Stanley Gardner and S. J. Perelman.

Farewell, My Lovely is an advance over even the very fine

Big Sleep. The plot is similarly picaresque, with a similar double-twist ending, but here Chandler has Marlowe more firmly in control. Marlowe’s qualities are also more confidently rendered: his rapid assessments of other characters, his idiosyncrasies — putting on his pajamas and going to bed when he’s expecting both the villain Malloy, and a lady — his drinking habits, his sudden moods of liking or compassion for a down-and-out informer or minor thug, his innate fastidiousness, and above all a certain generosity of spirit, even trustfulness, beneath the surface cynicism, qualities that must have been a lot like Chandler’s own.

His critical reputation continued to outpace his sales and readership. He rose to cult status in England following praise of his work by W. H. Auden and Somerset Maugham, and American critics eventually followed suit. One definition of art demands that the effort of the artist be somehow apparent, not in the sense of strain but of loving effort lavished on his medium, ‘pains’, as one critic called it, and it was this quality that attracted Edmund Wilson, who excepted Chandler from his general condemnation of detective stories. Chandler himself considered his writing to be art and wanted to make sure no one missed that — he included in his books both literary observations, as when Marlowe recognizes the source of the cocker spaniel Heathcliffe’s name or alludes to Pepys’s diaries, and just enough fancy writing to make the point. Despite his little barbs at modernist writers (he describes Hemingway as ‘a guy that keeps saying the same thing over and over until you begin to believe it must be good’), he shares many of the same almost Deco aesthetic qualities of hard-edged stylization.

Chandler has nearly limitless powers of description, whether full-dress, as in his long portraits of the Sternwoods in

The Big Sleep, or in his jewel-like little pictures of any minor character: ‘a sloe-eyed lad in a blue mess jacket with bright buttons, a bright smile and a gangster mouth, handed the girls up from the taxi’, or a clerk who has a ‘washed-out blue smock, was thin on top as to hair, had fairly honest eyes and his chin would never hit a wall before he saw it’. Sometimes he tosses off a casual simile — ‘Her eyes became narrow and almost black and as shallow as enamel on a cafeteria tray’ — and sometimes contents himself with an offhand phrase: someone is ‘drunker than a legion convention’, another character is ‘a ruthless permanent’. He never fails to render vivid, almost indelible, the least members of his panoply of sexy, predatory women, cops and underworld characters.

A modern, politically correct reader will be struck by the absolute lack of political correctness in Marlowe’s world, and perhaps be startled by the embarrassingly crude ethnic and gender slurs. We have dinges and shines, dames and tramps, limp-wristed male cuties, ‘short, dirty wops’, ‘greasy sensual Jews’, and ‘almost clean’ Chinamen. The explanation for the language lies, no doubt, in verisimilitude; Marlowe and Chandler lived in a competitive, dangerous, and not overly polite post-Depression world. At best, it conveys Chandler’s relish for vernacular speech, and especially American speech, in which he found a colorful pungency absent from the polite diction of Dulwich. But it also depicts an unusually hostile city of armed people ready to pull knives or take a swing at

Marlowe unprovoked; whether that was the reality of the time, a reflex of Chandler’s own world view, or an Englishman’s appalled perception of a tough frontier, is not always clear.

Some critics have found

The High Window, Chandler’s third Marlowe novel, which he struggled to write over the next two years, a falling off from the first two. It is true that in the beginning of the book, the wisecracking Marlowe is irritatingly elliptical, the chip on his shoulder almost insurmountably present. Perhaps that was a result of Chandler’s fatigue and growing restlessness, but the effect is to intensify the reader’s impression of Marlowe’s alienation and inner despair, qualities that serve to elevate him even farther above the cohort of tough detectives from which he sprang. The plot — Marlowe is hired to find a valuable coin — is as clever as usual, and infinitely clearer, the characters as vivid, the whole somehow a little closer to normal life than were the sinister underworld figures and nymphomaniac daughters in

The Big Sleep. The characters are in general more sympathetic; though the reader somehow likes the grumpy Mrs Murdock more than Marlowe does, he draws us into sharing his liking for Phillips and Mr Morningstar, two characters who will be murdered, increasing the impact for the reader of their bloody fates.

The High Window was published in 1942, and, still tired and restless, Chandler rapidly wrote

The Lady in the Lake, 1943. But he was spoiling for a change, so after the publication of this fourth Marlowe novel (see volume 2), he entered a new phase of his life, working for Hollywood, where he would make more money, gather more fame, go back to drinking with the legendary self-destructiveness that marked the careers of Hammett, Fitzgerald and Faulkner in Hollywood, and write only three more novels in the nearly twenty years that remained to him.

Copyright © 2002 by Raymond Chandler. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.