Excerpted from the Introduction

I N T R O D U C T I O N

Death is killing me. . . . this is London; and there are no fields. Only fields of operation and observation, only fields of electromagnetic attraction and repulsion, only fields of hatred and coercion. London Fields was published in September 1989. It did not foresee a long future for the planet. The novel is set in 1999, ten years on, and doomsday is predicted to arrive in January 2000. There remain, over the blazing hot September/October months which the narrative covers, only a few weeks before what is vaguely called the ‘Crisis’, or ‘Totality’, heralded by a total eclipse and terminal darkness. ‘Countdown to catastrophe’ is the novel’s time-frame.

But what kind of catastrophe? It’s not clear what form the rider of the ad 2000 apocalypse will take – nor, oddly, does the novel seem much to care. A colliding asteroid perhaps. Or a new alignment of the sun, itself going through a crisis of solar supergranulation, its evil rays glimmering through ominously ‘dead clouds’. A voracious black hole may be swirling towards the solar system invisibly, sucking into its vortex light, heat and soon planet earth as well. The authorities have scheduled a ‘cathartic’ exchange of nuclear weaponry. It is all up in the air. As the sandwich-men used vaguely to proclaim, the end of the world is ‘nigh’. Very nigh. But, as one of the characters in the novel puts it, ‘Life goes on innit’. For a month or two.

London Fields is the second part of Amis’s so-called ‘London Trilogy’ The man who is ‘tired of London’, said Samuel Johnson, is ‘tired of life’. Martin Amis would seem to be extremely tired. Amisian London is the suppurating bubo of a plague planet: a city where the tap water ‘had passed at least twice through every granny’. Weather forecasts are so horrific that they are broadcast late at night, after the children have gone to bed. The city is bathed in the corrupt ‘afterglow of empire’, as lingeringly poisonous as radioactive half-life. ‘And this also’, says Conrad’s Marlow in

Heart of Darkness, looking down the Thames towards the great luminous city, ‘has been one of the dark places of the earth.’ In

London Fields it is again a dark place – terminally dark.

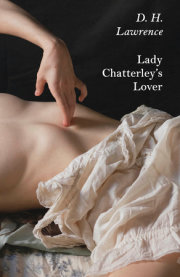

Like D. H. Lawrence (a writer alluded to in

London Fields) Amis sees the great tree of life, Yggdrasil, as dead to the roots in England. It can never grow again. But unlike Lawrence – who, after the First World War, embarked on his ‘passionate pilgrimage’ round the world to discover vitalities in places untouched by the catastrophe (largely where men did not wear trousers) – there is nowhere to go in Amis’s blighted world. ‘Totality’ means just that. It’s all over. Goodnight planet earth. And good riddance.

In a teasing foreword ‘M.A.’ confides to the prospective reader that he passed sleepless nights before coming up with the title. For those who know the city, particularly those who have house-hunted in it, forget any topographical association with the actual

London Fields, E8 (Hackney). That location never crops up in the narrative. The novel’s action is centred on the other side of the city, around Portobello Road and its W11 environs – Amis’s stamping ground in the 1980 s. The other main candidate title was, we are told,

Millennium – but Amis finally judged it to be too hackneyed. ‘Everything is called

Millennium just now’ (in Germany, one is told, the novel was retitled 1999).

What, then, did Amis intend us to understand by ‘

London Fields’? A main allusion, one suspects, is to Falstaff ’s babbling about ‘green fields’ on his deathbed. The verdant fields evoke ‘London like it used to be’. Pre-urban. Urban London destroys fields. That’s its reason for being. The city aims to extend itself, with concrete, steel, tarmac, bricks, glass and garbage, ‘right up to the rocks and the cliff s and the water’. You will no more find green fields in modern London than undergrowth and men with smocks and crooks in Shepherd’s Bush, or herons over Herne Hill, or cows munching contentedly outside Chalk Farm tube station. Peter Kemp, an astute commentator on

London Fields, sees it as a ‘pastoral title savagely inappropriate to its inner-city setting, [which] vibrates, like all Amis’s work, with the force fields of sinister, destructive energies’.

Amis, finally unburdened of his tedious ‘

enfant terrible ’ epithet, was forty years old when

London Fields saw print in 1989. Life begins at that age, says the dubious proverb. The number is not something that gave Martin Amis new pleasure in life. In interviews given around the cross-over period he confided that ‘the message has got through’. He was mortal and racked by the fact. ‘When middle age comes, you think you’re dying all the time’, his forty-something narrator bleakly observes. The forty-year-old author himself is quoted as saying, ‘looking at death is a full-time job’ – a job which he performs more conscientiously than most of us do in

London Fields. Martin Amis, behind and outside the novel, but everywhere inside it, has, we apprehend, come to terms with the irreversible fact, that as the singer-poet Jim Morrison put it, ‘Nobody gets out of here alive.’ Life sentence, death sentence – what’s the difference?

London Fields is dedicated by Martin to his father, Kingsley Amis. He, too, was much preoccupied with death as a subject. It is proclaimed most aggressively in the title of his 1966 novel,

The Anti-Death League, In the 1980s, as

London Fields was distantly taking form in Martin’s mind, his father produced, among other late-career masterpieces,

The Old Devils (1986), the study of terminal decay and imminent demise which won Amis Sr his long overdue Booker. It would have been nice, and wholly appropriate, for

London Fields to have won Amis Jr the award three years later. But he had put too many noses out of joint. He may have been well past infantile, but he was still, in 1989, too terrible a middle-aged man for many tastes.

London Fields opens, disarmingly, with a set of pseudo-candid definitions of what is to come which, like the title, will set the reader running in entirely wrong directions:

This is a true story but I can’t believe it’s really happening. It’s a murder story, too. I can’t believe my luck. And it’s a love story (I think), of all strange things, so late in the century, so late in the goddamned day. The reader is hereby primed for docufiction, crime fiction, romantic fiction and science fiction. It’s none and all of these. The speaker is Samson Young. He is creating a novel within the novel, but he will not, as we shall discover, be the final novelist. Indeed, at times, Samson seems to be incapable of keeping possession of any important part of the narrative, which is constantly slipping through his fingers as he writes it. Unlike his biblical counterpart, Samson is neither young nor strong, but like him, though less dramatically, he is losing his eyesight. We learn that he is in stage four of a terminal illness. What the illness is, we are not precisely told. But the fact that his dead father was a scientist working with plutonium is a broad hint. As a novelist Sam has another severe handicap. He can’t invent. He can only report on the characters who – like clockwork puppets – he winds up and lets go. Once created by his mind they go their own wayward way, however hard he tries to keep them in line and create some kind of ‘story’ out of what they’ve decided, often against his wishes, to do.

It’s rich territory for postmodernist jests. The heroine Nicola, for example, asks Sam at one point to ‘edit out’ another character who is really getting on her nerves. The novelist declines. He banishes the complainant from the immediate story. Later he has sex with her. ‘It doesn’t matter what anyone writes any more,’ he ruefully concludes. ‘Man, am I a reliable narrator’, he exclaims elsewhere. He isn’t. At times he can’t even claim to be an unreliable narrator. He’s just around at the scene of the action which he has somehow set going.

It is one of the many snares for the reader of

London Fields that the novel has what looks at first sight like a geometrical structure – it’s shapely, architectural even, in its formal layout. The table of contents is set out in triplets and sextuplets, the chapters making up the ‘pleasingly symmetrical’ and circadian number of twenty-four. Euclidean is a word which comes to mind. The chapters themselves conform to the same symmetrical shape – each beginning with Sam’s voice-over lead-in. But the narrative, which runs like mercury through these structures, is chaotic, fluid, at any point wholly unpredictable.

Amis was deeply interested in theoretical physics at this stage of his life.3 Quantum mechanics and the mysterious unfixities of sub-atomic particles seem to have been something he was pondering in

London Fields. Sam, at one point, muses on ‘Heisenberg’s principle that an observed system inevitably interacts with its observer’. Indeterminacy makes for a novel which is infinitely rewarding, but not for the faint-hearted reader. My head, I confess, aches when I try to take on board the Heisenberg uncertainty principle that sub-atomic reality changes, simply because you are looking at it. Or that a particle can be in two places simultaneously. The novel requires a kind of continuous double-think. Sam, too, is in two places at once, both outside and inside his novel. A novel which changes, simply because we are reading it.

In an important sense Amis’s novel seems to be in two different places, or time zones, at once. Although it’s stated (always parenthetically) that the action is happening in the late 1990s, the ‘feel’ of the novel is much more the 1970s and in places the mid-1980 s. Low-life characters, for example, are wearing ‘flares’ and clacking around in ‘Cuban heels’ (finery as antique as woad in 1999), and slaver over their porn on VCRs. There are no computers, no mobile phones. The world would have ground to a halt in 1999 without its digital ‘chips’ (many Y2 K nightmares were concocted on just that theme). They are non-existent in this chipless narrative. Engelbert Humperdinck and Barry Manilow (sixty-three and fifty-six years old respectively in 1999) are warbling anachronistically in the background. The Soviet Union still exists as one of the world’s two superpowers (the Berlin Wall actually fell two months after the publication of

London Fields. The Evil Empire was wobbling, terminally, as Amis was writing.) No British prime minister or government is mentioned in the text. But incidental jokes such as the following point strongly towards Mrs Thatcher’s 1980 s: ‘In a bold response to an earlier crisis, it was decided to double the number of council flats. They didn’t build any new council flats. They just halved all the old council flats.’ So when is the novel ‘set’? 1970 s, 1980 s, or late 1990 s? A category mistake. The narrative, like that elusive particle, is in many historical places at once. It depends on where you are when you look at it.

Copyright © 2014 by John Sutherland. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.