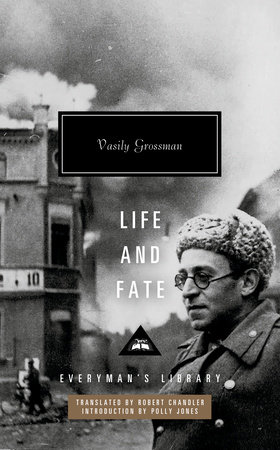

From the Introduction by Polly Jones

One of the longest and most ambitious novels of the twentieth century, Vasily Grossman’s

Life and Fate (completed 1960) is many things at once. Most simply, it recounts the extraordinarily brutal and heroic defence of Stalingrad in late 1942 and early 1943, which the author had begun to dramatize in the novel’s ‘prequel’

For a Just Cause (first published 1952) and earlier reported on as the longest-serving journalist at the Stalingrad front. The novel travels between the battle’s several fronts, but also to Moscow and to evacuee life in Kazan and Kuibyshev (now Samara). Those not directly involved in the fighting are drawn into other, potentially lethal battles with Stalinist bureaucracy and restrictions on free speech and research, or with its police and penal system. Earlier than Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag fiction, Grossman’s novel shows the Soviet prison system, from the ‘sleepless’ secret-police headquarters in Moscow to the remote Soviet camps. Yet more scandalously, it compares the Gulag to the Nazi camps and gas chambers, and Soviet ideology to national socialism, concluding that the two totalitarian states were each other’s mirror images, rather than polar opposites. Whence the novel’s deepest political and philosophical meditations on freedom and humanity: how, it asks, could the individual, and individuality itself, survive the ‘tragedy of the twentieth century’?

Small wonder, then, that none of Grossman’s contemporaries believed that the novel could be published in the Soviet Union. They were proved correct when the manuscript was turned down by the Soviet literary journal

Znamia in 1960, and then ‘arrested’ by the KGB the following year. Famously, the party’s then ideological chief Mikhail Suslov forecast that the novel would remain unpublishable for over two centuries, and Grossman’s lobbying of Khrushchev did nothing to alter the verdict. In the event, the confiscated manuscripts resurfaced in a Russian archive half a century later. Publication proved possible rather sooner, though Grossman died of cancer in 1964, without knowing (or believing) that it would. Manuscripts concealed and microfilmed by Russian friends travelled Westwards in the luggage of émigré writers and Western diplomats in the second half of the 1970s, leading to publication of the full text in Switzerland in 1980. Its first Russian edition appeared only in 1988 during Gorbachev’s glasnost. The posthumous, foreign (

tamizdat) publication of Grossman’s greatest novel, along with several shorter works also unpublished in his lifetime, means that Grossman’s status as one of the greatest twentieth-century Russian writers has been recognized belatedly, and still incompletely.

Life and Fate captures key facets of Grossman’s identity as a Jewish, Russian and Soviet writer and intellectual. Born in late 1905, Grossman spent his childhood and youth between Ukraine and Russia (with a short spell in Switzerland), and his formative years straddled the revolutionary divide of 1917. Both his parents were active in left-wing circles, especially his father, who left the family when Grossman was young, but stayed close to his son throughout his life. Though he resided in Moscow for most of his literary career, Grossman never forgot his roots in the largely Jewish town of Berdichev in Ukraine, where his mother remained until her death (as dramatized in

Life and Fate). His science degrees in Kiev and Moscow, and his early work as a chemist and engineer in the Donbass, sparked an abiding interest in science and industry, including a central storyline of

Life and Fate, about the physicist Viktor Shtrum.

Shtrum’s battles with anti-semitism in Stalinist academia also reflected another facet of Grossman’s biography. Alongside his contemporary and friend Ilya Ehrenburg, Grossman emerged from the 1930s onwards as one of the most prominent Soviet Jewish writers. Both authors were secular and assimilated, yet also profoundly distressed by the Jewish tragedy of World War II, spurring their leading roles in the short-lived Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee. Through this organization and their publications, they sought to draw domestic and international attention to the Holocaust, especially on Soviet soil, but came under severe pressure in late Stalinism. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Grossman was forced to abandon

The Black Book project on the Holocaust, and to collude in state harassment and repression of Jewish intellectuals, while enduring anti-semitic attacks himself.

These clashes with the Soviet authorities underpin the novel’s reflections on the moral and personal costs of complicity with state power. Neither Grossman’s reluctant signing of a letter in support of Stalinist repression, nor his reputation as a budding ‘red Tolstoy’, could protect his novel

For a Just Cause from years of bruising censorship before its publication in 1952, whereupon it almost immediately suffered a backlash from the Stalinist authorities and Soviet press. The experience left Grossman agonizingly aware of the precarity of Soviet critical acclaim and fame, yet he persisted in writing, and later defending, its audacious sequel. While minor works and translations were published in the early 1960s, his final years were largely characterized by unpublished writing (including works written ‘for the desk drawer’, such as his last major opus,

Forever Flowing, also later smuggled and published abroad), and by unequal battles with Soviet officialdom. This has led some to term this once celebrated Soviet writer a ‘dissident’ by the time of his 1964 death.

Like the author himself, Grossman’s writings are hard to categorize. They comprise journalism and essays, historical and philosophical reflection, epic and modernist narratives, vast novels, and elegant short stories.

Life and Fate, which he saw as his life’s work, combines many of these narrative approaches, but is rooted in eyewitness testimony, gathered over years of reporting on Soviet fighting and Nazi atrocities. There was nothing unusual in this emergence from journalism into literature. The lines between the two had been blurred since the revolution, as Soviet authors blended fact and fiction in writing about the Civil War, and later the industrialization and collectivization of the late 1920s and 1930s. In the latter period, Grossman made his name through journalism (including dispatches from the new industrial city of Magnitogorsk), short stories (notably

In the Town of Berdichev, 1934) and a long first novel,

Stepan Kol’chugin, serialized from the late 1930s and drawing heavily on his work as a mining engineer. By the time of this novelistic debut, the state literary doctrine of Socialist Realism was already insisting that Soviet writers ‘show reality in its revolutionary development’, which in practice meant substituting an optimistic projection of progress towards communism for empirical observation. Yet there was not long to adjust to these requirements before the outbreak of World War II.

Alongside better-known contemporaries, such as Ehrenburg, Konstantin Simonov and Aleksandr Tvardovsky, Grossman signed up to be a war correspondent as soon as Operation Barbarossa began on 22 June 1941. Deeply embedded with Soviet troops (unlike Ehrenburg, who was kept further from the front), Grossman followed the chaotic defeats and retreats of 1941–2, stayed in Stalingrad for much of the battle, and then travelled all the way to Berlin in May 1945. Throughout, his war sketches appeared in the Soviet press, especially the army newspaper

Red Star (whose editor, David Ortenberg, was a valuable patron, especially for Jewish war correspondents). His novel

The People are Immortal (1942) became one of the first and most enduringly popular Soviet war novels. This wartime writing brought him fame on an entirely different scale to that of the 1930s. Evocative, compassionate, and patriotic, it was exactly what the Soviet war effort needed, certainly in the early war, when Stalin himself conceded that ‘we will not rouse the people to victory with Marxism-Leninism alone’. His war prose struck a delicate balance between emotional and psychological authenticity, and a genuine belief in the patriotism and heroism of the Soviet soldier and the people (

narod) as a whole. Indeed, this belief permeated all his writing about Stalingrad, constituting his key justification for trying to publish both

For a Just Cause and

Life and Fate.

Alongside this wartime tolerance for greater emotional and psychological complexity, the Soviet authorities briefly sanctioned investigation of Nazi atrocities. Though his admiration for the Soviet soldier and the heroism of victory ran deep, Grossman felt an even more profound ethical imperative to communicate to the Soviet, and international, audience the horror of the Holocaust. By the time that he visited liberated Nazi camps and published ‘The Hell of Treblinka’ (1944), later used in the Nuremberg trials, he was aware that his mother had died in the near-extermination of the Jewish population of Berdichev, in September 1941. He had also gathered evidence of mass killings of Jews on work assignments in Belorussia and Ukraine. His resulting commitment to capturing the mass and individual tragedies of the Holocaust was hardly satisfied in the short interval in the late war when the theme was permitted. Nonetheless, that time provided opportunities to visit sites of atrocities and interview dozens of witnesses, furnishing key material for the abortive

Black Book project and for

Life and Fate’s depiction of massacres of Soviet Jews, Nazi POW camps and gas chambers. A decade later, Grossman put his journalistic skills to new use, interviewing friends who had returned from the Gulag and relatives of deceased prisoners, albeit in strict secrecy. These testimonies were essential to the novel’s depiction of the Soviet camps, providing an authentic picture of a world that he never witnessed up close, even though many family members and friends were victims of Stalinist repression.

Although his extensive experience of journalism and what we might term oral history was formative and fundamental, Grossman was also a profoundly literary writer, in constant dialogue with Russian and world literature. He transformed and transcended his factual material, through lifelong, eclectic reading of literature, history, philosophy and science. This was true even of his journalism, which distilled psychological depth and quasi-universal truths from its eyewitness portraits. The Stalingrad diptych, and

Forever Flowing, were more ambitious in scope and form, and increasingly radical in their political and philosophical arguments. All blend eyewitness testimony and real-life prototypes with historical overviews, and philosophical and political analysis. Although

Forever Flowing, arguably unfinished at the time of his death, is his most fragmentary and modernist work, the Stalingrad diptych also sweeps its reader back and forth, between microscopic portraits of military and domestic life and panoramic overviews of world history and human nature.

Although the two Stalingrad novels are inextricably connected, the historical and philosophical breadth and depth of

Life and Fate far outstrip Grossman’s achievement in

For a Just Cause. The same is true of its much broader dialogue with texts and authors including the Bible, ancient philosophers, Chekhov, Dostoevsky and, of course, Tolstoy, whose

War and Peace was one of Grossman’s favourite and most frequently reread books. However, to call

Life and Fate a twentieth-century

War and Peace hardly does justice to its startling blend of taboo-breaking historical investigation, profound philosophical thought, and literary innovation. The challenges to humanity were immeasurably greater in the era of total war, atomic science, and totalitarian ideology than in Tolstoy’s time. Grossman sought to capture the scale and the ethical and literary challenge of unprecedented human suffering, while rooting the drama of Stalingrad and Stalinism in the timeless struggle for humanity and the individual soul.

*

Life and Fate, like its prequel, is arranged around a single family, the Shaposhnikovs: three generations of women, and their husbands, lovers, children, friends and colleagues. The family radiates out, spoke-like, across the Soviet front and rear, from Stalingrad to the Russian provinces, the Gulag, and the Holocaust in Ukraine. It is a device consciously borrowed from Tolstoy, resulting in a cast of several hundred named characters, and used to similar effect. Ultimately, this panorama of Soviet life, like Tolstoy’s reflections on Russia in the Napoleonic wars, reflects on individual and collective identity and belonging, and on freedom and unfreedom (albeit largely state-constrained, rather than divine determinism). Like its prequel,

Life and Fate roams into enemy territory too. This time, however, it shows not just the Nazi elite’s decision-making, but also the horrific concentration camps that result. The novel’s nuanced portraits of ordinary Germans, including low-ranking soldiers and everyday perpetrators, are yet another innovation.

Although

Life and Fate progresses from August 1942 to the aftermath of the victory in Stalingrad in spring 1943, it is not a linear history. Instead, it is made up of blocks of chapters, each concerning a key protagonist and their network in a particular location. While more than half the chapters are set in Stalingrad (including over a dozen embedded with German troops), over fifty dramatize life in the rear, and almost the same number play out in Soviet or Nazi prisons and camps. The narrative thus switches repeatedly between military and civilian, Soviet and German, unfree and (ostensibly) free, life and death. On a handful of occasions, the reader is lifted out of the world of the novel altogether and plunged into philosophical and political reflections on the eponymous life and fate: another Tolstoyan feature. These frequent journeys between the novel’s worlds, and between dramatized narrative and analytical commentary, encourage the reader to seek out connections other than chronology. It turns out that the real battle is not Stalingrad, nor even the Soviet–Nazi war. Rather, every major character is engaged in a struggle to preserve their integrity and freedom. . . .

Copyright © 2022 by Vasily Grossman; Translated by Robert Chandler; Introduction by Polly Jones. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.