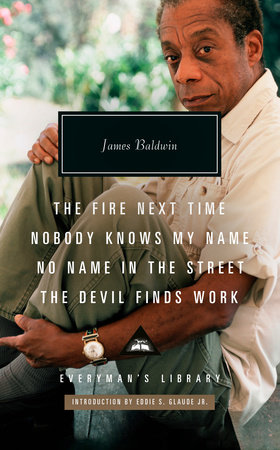

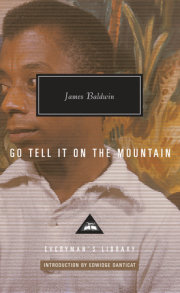

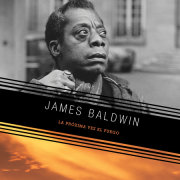

from the introduction by Eddie S. Glaude, Jr.

In 1986, about a year before his death, James Baldwin sat down with David C. Estes for the New Orleans Review to talk about his latest book,

The Evidence of Things Not Seen. It was a wide-ranging interview, a kind of retrospective of Baldwin’s career as a writer and a refl ection, in light of the new book, on his career as an essayist. It is in the context of this discussion that the question of how he became an essayist emerged.

How did he think about the form? How did he see himself as someone who inhabited the genre at the highest level? After all, at this point in his career Baldwin had stood for some time as one of America’s greatest essayists. In his non-fi ction writing, particularly in the books collected here, Baldwin offered the most searing and insightful commentary on the vital questions of race, culture, and American democracy. His prose gave the nation a language in which to think about itself differently, loosed from the shackles of ideas of American exceptionalism and the illusions of whiteness that led some to believe that somehow, no matter what God said, the color of one’s skin accorded one value above or below every other human being. On the page, he forced a confrontation with the ugliness of who we are, and he did it in such a way that might have made Montaigne nod his head in recognition. Simply put, Baldwin had mastered the form.

In this interview with Estes, however, Baldwin admitted that he “never intended to become an essayist.” It was working with Saul Levitas at The New Leader and with Robert Warshow at Commentary when he was in his early twenties that helped him find his feet in the genre. His first inspiration came from the flaccid race books he had to review every week at

The New Leader, which made clear to him that he could not write from the vantage point of a victim. Baldwin developed his approach to the question of race and American democracy in contrast to the all-too-common stale sociology and tangled web of social statistics that purported to reveal the problems of American race relations. As a young man writing reviews for

The New Leader, he had his fill of such books. Sentimental accounts that treated Black people as victims. Books that refused to attend to the complexity of peoples’ lives only, in the end, to tell us to “be kind to niggers” and “be kind to Jews.” Instead, Baldwin took his readers beneath the surface of the country’s malaise to tap the root. There he asked the moral question of who we take ourselves to be as individuals and as Americans. In doing so, he forced a painful encounter with experience (with life), historical and present. That honest encounter, he insisted, could free us to deal with who we might possibly become by releasing us from the straitjacket of our national illusions. A confrontation with what torments the nation and with the pain and wounds that move us about meant keeping track of the material conditions of American life and the inner lives of those who had to bear it all. For Baldwin, and these essays make the point explicit, the unwillingness of Americans to reckon with the suffering at the heart of the country’s identity—to evade the history that makes them who they are—has made them monstrous.

Americans often long for the illusions of safety that trap us in categories while we retreat into sentimentality that gums up our ability to feel. “Sentimentality, the ostentatious parading of excessive and spurious emotion,” Baldwin wrote in “Everybody’s Protest Novel” (1949), “is the mark of dishonesty, the inability to feel; the wet eyes of the sentimentalist betray his aversion to experience, his fear of life, his arid heart; and it is always, therefore, the signal of secret and violent inhumanity, the mask of cruelty.” Baldwin published those words when he was twentyfour years old. He would echo the sentiment some twenty-plus years later in

No Name in the Street with a description of the “wet eyes” of a powerful white man in the South, “staring up at [his] face, and his wet hands groping for [Baldwin’s] cock, we were both, abruptly, in history’s ass-pocket.” Race, desire, and emptiness felt in an unwanted touch.

But, again, reading Baldwin requires more than tracking the pain and suffering of the nation and of himself. He does not speak as a victim. Baldwin is a poet in Emerson’s sense: that person who “shall draw us with love and terror” and “chaunt[s] our own times and social circumstance.” He is an artist, a writer, in conversation with a wide range of influences (inheritances and ancestors) that shape what he sees and how he inhabits the genre. To read him is a demanding practice: to track how the language and blues sensibilities of Black folk in the United States shape the writing; to sit with the ways the King James Bible and the homiletic structure of Black preaching influence the form; and to trace his references and invocations (to see, for example, the infl uence of Henry James in his sentence structure and the ongoing engagement with the themes that animated James’s novels like The Ambassadors, or how he riffs on Emerson’s essay “Self-Reliance,” and Marcel Proust’s refl ections on time and memory), and to do this work across a wide-ranging corpus of close to seven thousand pages.

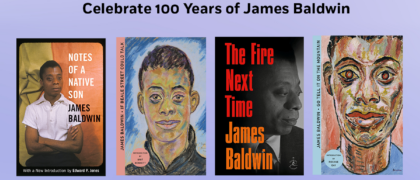

This collection begins in 1961 with

Nobody Knows My Name and ends with

The Devil Finds Work, published in 1976. From the height of the civil rights movement with student sit-ins, the March on Washington, and the peak of his fame with his face on the cover of

Time Magazine to the stain of Watergate, the election of Jimmy Carter, and the burden of being a celebrity artist now in his fi fties with a political movement in ruins, these essays offer the reader a sense of the complex arc of Baldwin’s witness and craft.

With the publication of

The Evidence of Things Not Seen in 1985, the “old man” had occasion to look back and to look forward. As he resisted Estes’s question about the New Journalism and the distinct form of Evidence, he recalled a lesson learned from Saul Bellow. “I’m speaking only for myself . . . I don’t think a writer ever should show off, anyway. Saul Bellow would say to me years and years ago, ‘Get that fancy footwork out of there.’” A lesson for writers, still. In this short interview, Baldwin revealed what sits at the heart of his essay writing, how that journey began, and how just a year before his death it ended. This Everyman’s Library edition, implicitly framed by Baldwin’s fi rst and last books, takes up what happened in between, a writer who finds his voice on the page and, by extension, in the world.

In the late 1940s, Baldwin learned from the editorial pen of Warshow that, if he was not going to lie on the page, he had to confront his own fears and terrors. He had to deal with the overbearing presence and image of his stepfather. He had to grapple with desire; not only his sexual desire but his desire to be loved. He had to face the rage deposited in his gut by a world that announced from his birth that he was inferior simply because of the color of his skin, and he had to admit, if he was to assert his right to live fully, that at one point in his life he tragically believed what the world said about him. Baldwin had to plumb the depths of his own perspective, which required he find out exactly what his perspective was. “I couldn’t talk about ‘them’ and ‘us,’” he said to Estes. “So I had to use ‘we’ and let the reader fi gure out who ‘we’ is. That was the only possible choice of pronoun. It had to be ‘we.’ And we had to figure out who ‘we’ was, or who ‘we’ is.” The slight and playful shift to Black English, “who we is,” reveals how, for him, Black people reside at the heart of the answer to that question. Autobiography became a ready-to-hand resource, not because his life was interesting—everybody suffers; everyone must make choices that are theirs alone—but, as he put it, “in my social situation . . . I had to use my personal dilemma to illuminate something. I repeat, I am not speaking from the point of view of the victim. I am speaking as a person who has a right to be here.”‡ That insistence combined with a fearless interrogation of the circumstances that shaped his life, both materially (he grew up poor in Harlem) and in his most private, interior moments (where love and desire co-mingled with race), gave his essays a sense of urgency and power that continues to inspire and unsettle.

In the end, Baldwin took himself to be a witness and from that perch he tackled the social and moral questions that confronted the nation and confront each of us. As such, these books offer biting commentary on the state of American life and are deeply personal. I have no doubt Baldwin would agree with Virginia Woolf—another literary stylist and social critic—that the principle guiding the essay must be that of pleasure. But it also demands more. Woolf writes that the essay “should lay us under a spell with its first word, and we should only wake, refreshed, with its last. . . . The essay must lap us about and draw its curtain across the world.” That is how Baldwin brings us such clarity. He wrote not for pleasure alone, but that we might, in the end, become better human beings. The moral concern is the beating heart of Baldwin’s prose.

The open form of the genre of the essay requires a kind of candor that often escapes our talk of race in the United States. Americans lie to themselves repeatedly, and that self-deception immobilizes the country, as Baldwin told Estes, “with a past it cannot explain away.” That complicated history is habitually buried beneath tidy self-representations that declare, despite our national sins, we are always on the road to a more perfect union. But Baldwin’s essays rend the country’s illusions by demanding an honest assessment of the way race distorts and disfi gures not only the nation but individuals, white and black alike. His sentences sometimes rage. They cry out like the prophets of old. And yet, as I have suggested, something deeply personal and private is at work here. Confessional even. To be sure, Baldwin’s essays are about the nation and the diffi cult questions of race, culture, and democracy, but they are also extraordinary efforts at self-creation, where the poor child of Harlem, born on August 2, 1924 to Emma Berdis Jones, who managed to survive the rages of his stepfather, David Baldwin, wills himself, with the aid of the likes of Beauford Delaney and others, to become one of the world’s greatest writers. He inhabits the genre of the essay as both prophet and romantic, as one who warns of the fires to come and as the writer who declares near the end of his life, “I have nothing to prove. The world also belongs to me.” Here insight reaches towards the world and towards the soul—a kind of soul-making prose.

These essays are, at once, intimate and expansive, vulnerable and relentless in their demands of the reader. They challenge and upset. Something close to the heart is happening on the page. In The Fire Next Time, for example, readers are allowed to eavesdrop on a conversation that happens behind the veil, behind a closed door in places that white folk rarely, if ever, enter. “To be loved, baby, hard, at once, and forever, to strengthen you against the loveless world,” Baldwin wrote to his nephew. “Remember that: I know how black it looks today, for you. It looked bad that day, too, yes, we were trembling. We have not stopped trembling yet, but if we had not loved each other none of us would have survived. And now you must survive because we love you, and for the sake of your children and your children’s children.” This is intimate knowledge being passed from one generation to the next. Something akin to what my father told me as the shadow of the veil fell over my own teenage eyes.

Copyright © 2024 by James Baldwin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.