Chapter 1

Notes of a Native American

The Story of a Friendship in Black and White

Sol Stein

One thing you always have to keep in mind is how little you can take for granted. When one talks about the sixties, for example, one tends to assume that everyone knows what you're talking about, but, in fact, many of them were hardly born yet when the sixties were going on. That means you have to rethink everything as if it happened in ancient Rome or Greece.

-James Baldwin in Contact,

a publication of the University of Massachusetts

at Amherst, January-February 1984

I am remembering five thousand people crowded into the Cathedral of St. John the Divine for James Baldwin's funeral, and I imagine my lifelong friend Jimmy and me watching that event, an elbow poking the other's rib for attention as in the old days when our lives intersected.

I knew James Baldwin first in our early teenage years, when I was thirteen and he was fifteen. It all began in the tower of DeWitt Clinton High School in the north Bronx at a time when students anywhere in the five boroughs of New York City didn't need to be bused anywhere but could elect to go to a high school of their choice. Baldwin, known then and since as Jimmy, went the distance by subway, bus, and foot from Harlem in Manhattan to DeWitt Clinton at the far northern edge of New York City, an exceptional school where his last formal education took place. In this day of failed busing, it is hard to imagine that in 1939 a poor boy could travel many miles to a different borough to seize an education he could not get locally.

When DeWitt Clinton first opened the doors at its present site in May of 1929, it claimed to be the largest secondary school for boys in the world. The three-story building and its athletic field and stadium occupied about twenty-six acres and had a single-session capacity of over five thousand students. A recently remodeled room just off its library displays a picture gallery of onetime Clinton students that includes such luminaries as Paddy Chayevsky, Countee Cullen, Burt Lancaster, Ralph Lauren, Jan Peerce, Richard Rodgers, A. M. Rosenthal, Daniel Schorr, Neil Simon, and Lionel Trilling. Clinton was a garden in which black and white teenagers could become fast friends, an environment that a few years later made possible Notes of a Native Son, which in 1999 was selected by a distinguished panel as one of "the 100 best nonfiction books of the century."

Our home away from home was in what we called the Magpie Tower, the place where DeWitt Clinton's award-winning literary magazine, The Magpie, was edited by students as young as thirteen and fourteen. Our core group, besides Baldwin and me, included Richard Avedon and Emile Capouya, working under the tutelage of a faculty member, Wilmer Stone. Avedon was then a poet and shy. When we were called upon to sell the issue of January 1941, Avedon and I would stand in front of each classroom, Avedon silent, his hands clasped in front of him, while I recited a poem of his from memory. America had not yet formally entered World War II, but London was burning. Avedon's poem that lingers still in my memory is about the loss of a childhood friend in the firebombing of London. What we all wrote then is today mostly embarrassing, but the learning process was astonishing. On Friday afternoons, after classes officially let out, the Magpie gang would assemble in the tower above the three floors of the school building to hear our faculty advisor read our stories aloud to us in the most boring monotone imaginable. We were eager to see our stories in print and were learning to take criticism in a most painful way that was also instructive, for we learned then what all writers must eventually learn, that the reader has to be moved by the words alone, without help from the histrionic talents of the author.

Stone's private critiques of our work could be withering. Avedon told me a couple of years ago that on one occasion Stone asked him what kind of reading matter his parents had lying around the house. Avedon mentioned magazines like Good Housekeeping and McCall's. Stone told him, "That's what's wrong with your writing." At that moment, Avedon said, he decided to give up writing and turned, brilliantly, to photography.

More than forty years later, in the preface to the 1984 edition of Notes of a Native Son, Baldwin begins, "It was Sol Stein, high school buddy, editor, novelist, playwright, who first suggested this book. My reaction was not

enthusiastic: as I remember, I told him that I was too young to publish my memoirs. I had never thought of these essays as a possible book. . . . Sol's suggestion had the startling and unkind effect of causing me to realize that time had passed. It was though he had dashed cold water in my face. Sol persisted, however. . . ."

I don't remember Baldwin's resistance to doing the book. I do remember the editorial process, helped by recently finding my line-by-line editorial notes and Baldwin's responses, which are included in the correspondence section of this book. Writers can be wary of editors they don't know well. By the time Baldwin and I had to deal with Notes of a Native Son, the overlay of a friendship of a dozen years made the process easier.

A friendship that endures might reasonably be defined as a house in which disagreements are confined to an attic that can be opened for memoirs but never for continuation of a former argument. Baldwin and I came to our friendship with differences. He was black and I was white, he loved men and I loved women, he assumed his ancestors came to America in chains and I assumed my parents, who slipped over the border separately and illegally, came here because they had nowhere else to go. Despite the differences-we lived many miles apart-because of our friendship our families took a liking to each other. There are surviving photographs of Jimmy bouncing two of my pajama-clad children on his knee. I loved and admired Baldwin's mother, Berdis, and believed it was reciprocal even at our last warm meeting after Jimmy's death. Berdis visited with my family when Jimmy was abroad. I was welcome in Berdis's apartment on 131st Street in Harlem, but not by the policeman who stopped me outside and wanted to know what my white face was doing in that neighborhood.

Berdis had a secret that to my knowledge and Jimmy's say-so was never

divulged: the identity of Jimmy's father. The now legendary stepfather Jimmy wrote about was the preacher who married Berdis, presumably legitimized her son, and gave her eight more children. My mother, Zelda Zam, enjoyed Jimmy's brightness, his dancing hands. Like Berdis Baldwin, she had her secret. According to family legend, in the old country, hiding in the cellar during a pogrom, through a crack in the door my mother saw her first fiancé killed by one of Petlyura's Cossacks. In America she had another secret I discovered as a child during the Great Depression. In the old country, my mother at a young age was the head of secondary evening schools in Kiev, the largest city in the Ukraine. To make a living in America she sold Compton's Encyclopedia door-to-door, and one day, when the Depression bottomed, I opened the heavy sample case she took to work every day and found the knee pads she wore when cleaning other people's floors. Baldwin's mother, Berdis, may also have done the same.

Jimmy Baldwin and I, both Depression-era kids, responded differently to food. At my mother's table, Jimmy would eat like a bird, one small piece at a time, taking two hours over a simple meal, while I devoured all of it in the first few minutes. One might suppose that Jimmy was stretching out the pleasure of food, while I was gulping it down before it vanished. One of my few memories of Depression eating was the time my mother and father planted the single orange my father had brought home on the table and said, "You eat. We'll watch."

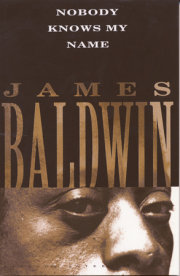

Though both of my parents came from Russia, I had trouble identifying with my mother's motherland, just as Jimmy later had trouble identifying with Africa. I remember Baldwin's rising hope in Nobody Knows My Name: "Africa was now on the stage of history. This could not but have an extraordinary effect on [the morale of blacks], for it meant that they were not merely the descendants of slaves in a white, Protestant, and puritan country: they were also related to kings and princes in an ancestral homeland, far away." Africa let Baldwin down. The dark continent produced corrupt kings and corrupt princes who robbed their people and kept them poor. Tribalism unleashed the wholesale butchery of millions, while in America, which Baldwin acknowledged as his only homeland, a black American, Colin Powell, had ascended to a position of power a few hearts away from the presidency of his country, though inner cities remained inert cities, fatherless and poor. Everything changes slowly, and human nature not at all.

Growing up, I wanted so badly to be thought of as an American and not as a sometimes despised Jew. Baldwin could instantly be seen as black by anyone. To the onlooker, I had no visible marks that at once characterized me as Jewish. Blond from birth, soon enough I was six feet tall. Observers knew me to be Jewish only after they knew my name, which left time beforehand for strangers to make anti-Semitic remarks in my presence, assuming me to be one of them. It is quicker to be typed as black, as different, as not belonging. The sting of later recognition of a Jew who doesn't look particularly Jewish can be startling.

When I was seven, in the sweltering New York summer kids could get into the swimming pool of Evander Childs High School by lining up to pay four cents for admission. One day the older boy behind me on line had a metal Star of David attached to the handlebars of his bicycle. I asked him if he was Jewish. He reared back. He didn't know the insignia he had found and affixed to his bicycle was a Jewish star. He asked if I was Jewish. I nodded, at which point he raised his fist and exclaimed, "You killed Jesus Christ!" It was the first such exposure for me. I will mention one more. Early in my two years as a soldier during the last part of World War II and after, before going overseas I was stationed briefly at a post near the University of Illinois in Champaign. I no longer remember how I came to date the homecoming queen of the university, but we quickly became friends. During my time away from base, I read poetry to her. We saw each other several times before June Saylor, somewhat embarrassed, said her parents wanted to know where my parents came from. Full of youthful romance, dismayed and hurt, I fudged, but not enough to make me acceptable to June's parents, however acceptable I might have been to her. It occurred to me that if I'd been black, we'd never have dated, and the sting of ethnic rejection would not have belatedly smashed what may have been the beginning of a courtship.

For better, not for worse, Baldwin and I were here, native Americans, charged up, yearning to make it as Americans while trying to shake up America to make it a more congenial nest for the likes of us. Before each of us was a lover of specific people, we were lovers of language, which if delivered well can have even more immediate power than print. Franklin Roosevelt read Sam Rosenman's words with a mesmerizing authority that helped lift the sagging spirits of Americans in a bad time. Churchill's rhetoric, drafted by himself, defied Hitler and defeat. Martin Luther King Jr., in his preacher's delivery, announced his dream. Much has been made of Baldwin's having been a teenage preacher, an influence that is evident in his incantatory prose and his ability to address readers as if they were his congregation. Not enough has been made of his early mastery of the writer's main task, putting to paper what other people only think.

Laymen speak of a writer's style. Writers and editors speak of a writer's voice, a distinguishing way with words that is recognizable and consistent. As an editor, I was attracted to Baldwin's writing because of his voice and his writerly intelligence, his use of visual particularity to make us see the places and people he was writing about. Once his reader was lured into the experience, Baldwin would let loose insights that were startling in their candor. At the behest of the publisher, I wrote a prefatory note for Notes of a Native Son, in which I said, "In the jargon of writers, 'pieces' is the word used to describe articles, essays, and the uncategorizable writings that constitute the writer's baggage while he is traveling between major works. Yet of Lord Acton, for instance, such 'pieces' are all we have; fortunately, they inform each other as well as us and constitute a whole. That is also the virtue of James Baldwin's pieces, a frightening virtue in one so young." When I saw the prefatory note in galley proof, I ordered it removed on the grounds that Baldwin's work didn't need my introduction. One can't escape error that easily, for I recently found the Library Journal review of Notes of a Native Son, made from a bound galley of the book, and there was notice of the introduction that no longer existed in the book itself.

Toward the end of his life, Baldwin said Notes of a Native Son was of crucial importance in his struggle to define himself in relation to his society. "I was trying to decipher my own situation, to spring my trap, and it seemed to me the only way I could address it was not take the tone of the victim. As long as I saw myself as a victim, complaining about my wretched state as a black man in a white man's country, it was hopeless. Everybody knows who the victim is as long as he's howling. So I shifted the point of view to 'we.' Who is the 'we'? I'm talking about we, the American people."

In the world of publishing and bookselling, it was believed that books of essays did not sell. Part of the problem was that putting a binding around random essays made for a random reading experience. A book demanded cohesiveness. The reader had to feel he was on a discernible path from the first page to the last, which meant a lot of attention had to be paid to the order of the essays. In addition, the first and last essays had to be chosen carefully, for the mission of the first was to get the reader to read on, and the mission of the last was to leave the reader with a strong impression of the book.

Copyright © 2004 by James Baldwin and Sol Stein. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.