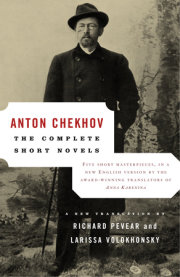

1

Moscow lies silent. From time to time screeching wheels echo in the wintry streets. Lights no longer burn in the windows, and the streetlamps have gone out. The ringing of church bells rolls over the sleeping city, warning of the approach of dawn. The streets are empty. The narrow runners of a nighttime sleigh mix sand and snow as the driver pulls over to a corner and dozes off, waiting for a fare. An old woman walks past on her way to church, where candles, sparse and red, are already burning asymmetrically, throwing their light onto the golden icon stands. The workers of the city are waking after the long winter night and preparing to go to work.

But fashionable young gentlemen are still out on the town.

Light flickers illegally from behind the closed shutters in one of Chevalier's windows. A carriage, sleighs, and cabs are huddling in a line by the entrance. A troika is waiting to leave. A porter, bundled in a heavy coat, stands crouching behind the corner of the house as if hiding from someone.

"Why do they keep blathering, on and on?" a footman sitting in the hall at Chevalier's wonders, his face drawn. "And always when it's my shift!"

From the brightly lit room next to the hall come the voices of three young men. One is small, neat, thin, and ugly, and gazes with kind, weary eyes at his friend, who is about to leave on a journey. The second, a tall man, is twiddling his watch fob as he lies on a sofa next to a table covered with the remains of a banquet and empty wine bottles. The man about to leave on a journey is wearing a new fur jacket and is pacing up and down the room. From time to time he stops to crack an almond with his thick, strong fingers, whose nails are meticulously clean. For some reason he is continually smiling. A fire burns in his eyes. He speaks passionately, waving his arms. But it is clear that he is searching for words, and that the words which come to him seem inadequate to express what has moved him. He is constantly smiling. "Now I can tell you everything!" he says. "It's not that I am trying to justify myself, but I want you, of all people, to understand me as well as I understand myself--I don't want you to see things the way a vulgar person would. You say that I have done her wrong!" He turns to the small man, who is gazing at him with kindly eyes.

"Yes, you have done her wrong," the small, ugly man answers, and it seems that even more kindness and weariness are reflected in his eyes.

"I know your point of view," the man about to leave continues. "You feel that there is as much happiness in being the object of love as there is in loving--and that if you attain it once, it's enough for a lifetime!"

"Oh yes, quite enough, my dear fellow! More than enough!" the small, ugly man says with conviction, opening his eyes wide and then closing them.

"But why not experience love oneself?" the man setting out on a journey says. He becomes pensive for a moment and then looks at his friend as if pitying him. "Why not love? I don't mean 'Why not be loved?' No, being loved is a misfortune! It's a misfortune because you feel guilty that you cannot return the same feelings, that you cannot reciprocate. Lord!" He waves his hand disparagingly. "If only this could all happen reasonably. But it seems to have a will of its own. It's as if I had made her fall in love with me. I know that's what you think--I know you do. Don't deny it! But will you believe me if I tell you that of all the bad and foolish things I have done in my life, this is the only one I do not and cannot repent of! I did not lie to her, not at the beginning and not later! I really thought I had finally fallen in love, but then I realized that the whole thing was an unintentional lie, that one cannot love that way. So I simply could not continue. And yet she did. Is it my fault I couldn't? What was I to do?"

"Well, it's all over now!" his friend said, lighting a cigar to chase away his drowsiness. "But one thing is clear: you have not yet loved, and you don't know what love is!"

The young man about to set out on a journey clasped his head in his hands, again wanting to express something, but unable to find words. "You are right! I have never loved! But I have a desire within me to love, a burning desire! Yet the question remains: Does such a love exist? Somehow everything is so incomplete. But what's the point of even talking about it! I have made a mess of my life, a complete mess! But you're right, it's all over now. I feel that I am about to embark on a new life!"

"A new life that you'll also make a mess of," the man on the sofa cut in.

But his friend did not hear him. "I am sad to be leaving but also happy," he continued. "Though I have no idea why I am sad." He began to speak about himself, not noticing that the others did not find the topic as interesting as he did. A person is never so much an egoist as in moments of rapture. He feels that at such times there is nothing more splendid or interesting than himself.

A young house serf wrapped in a scarf and wearing a heavy coat came into the room. "Dmitri Andreyevich, the driver says he cannot wait any longer--the horses have been harnessed since midnight, and it's already four in the morning!"

Dmitri Andreyevich looked at his serf Vanyusha. In the serf's coarse scarf, his felt boots, and his drowsy face, he heard the voice of another life calling to him--a life full of hardship, deprivation, and work.

"Yes, we must leave! Farewell!" he said, patting the front of his jacket to see if any of the hooks were unclasped. The others urged him to tip the driver to wait a little longer, but he put on his hat and stood for a moment in the middle of the room. The friends kissed good-bye--once, twice, then stopped and kissed a third time. He walked up to the table, emptied a glass, took the small, ugly man by the hand, and blushing said, "I must speak my mind before I go....I must be straightforward with you, because I love you dearly, my friend....You are the one who loves her, aren't you? I sensed it from the beginning...no?"

"Yes, I love her," his friend replied, smiling even more gently. "And perhaps..."

"Excuse me, but I have been ordered to put out the candles," one of the sleepy waiters said, hearing the last words of the conversation and wondering why gentlemen always kept saying the same things. "Who should I make the bill out to? To you, sir?" he asked, turning to the tall man, knowing very well that he was the one who was to pay.

"Yes, to me," the tall man said. "How much do I owe?"

"Twenty-six rubles."

The tall man thought for an instant but said nothing and slipped the bill into his pocket.

The other two friends were continuing their farewell. "Good-bye, you are a splendid fellow," the small, ugly man said.

Their eyes filled with tears. They went out onto the front steps.

"Oh, by the way," Dmitri Andreyevich said, blushing as he turned to the tall man. "Take care of the check, will you? And then send me a note."

"Don't worry about it!" the tall man said, putting on his gloves. "Ah, how I envy you!" he added quite unexpectedly.

Dmitri Andreyevich climbed into the sleigh and wrapped himself in a heavy fur coat. "Well, why don't you come along?" he said, his voice shaking. He even moved over and made room. But his friend quickly said, "Good-bye, Mitya! God grant that you..." He could not end his sentence, as his only wish was for Dmitri Andreyevich to leave as soon as possible.

They fell silent for a few moments. One of them said another farewell. Someone called out, "Off you go!" And Dmitri Andreyevich's driver set off.

One of the friends shouted, "Elizar, I'm ready!" And the cabbies and the coachman stirred, clicked their tongues, and whipped their horses. The wheels of the frozen coach creaked loudly over the snow.

"Olenin is a good fellow," one of the two friends said. "But what an idea to set out for the Caucasus, and as a cadet of all things! Not my notion of fun! Are you lunching at the club tomorrow?"

"Yes."

The two friends drove off in different directions.

Olenin felt warm in his heavy fur, even hot, and he leaned back in the sleigh and unfastened his coat. The three shaggy post-horses trudged from one dark street to the next, past houses he had never seen before. He felt that only travelers leaving the city drove through these streets. All around was darkness, silence, and dreariness, but his soul was filled with memories, love, regrets, and pleasant, smothering tears.

2

"I love them! I love them dearly! They are such wonderful fellows!" he kept repeating, on the verge of tears. But why? Who were these wonderful fellows? Whom did he love? He wasn't quite sure. From time to time he looked at one of the houses and was astonished at how odd it was. There were moments when he was surprised that the sleigh driver and Vanyusha, who were so alien to him, were sitting so close, rattling and rocking with him as the outrunners tugged at the frozen traces. Again he said, "What fine fellows, I love them dearly!" He even burst out, "I'm overcome! How wonderful!" And he was taken aback at saying this, thinking, "I'm not drunk, am I?" Olenin had drunk a good two bottles of wine, but it was not only the wine that had affected him: He remembered the words of friendship that had seemed so sincere, words that had been uttered shyly, impulsively, before his departure. He remembered his hands being clasped, looks, moments of silence, the special tone in a voice saying, "Farewell, Mitya!" as he was sitting in the sleigh. He remembered how sincere he had been. All this had a touching significance for him. He felt that it was not only good friends and acquaintances who had rallied around him before his departure. Even men indifferent to him, who actually disliked him, or indeed were hostile to him, had somehow resolved to like him and to forgive him, as one is forgiven in the confessional or at the hour of one's death.

"Perhaps I will never return from the Caucasus," he thought and decided that he loved his friends, and the others too. He felt sorry for himself. But it was not his love for his friends that raised his soul to such heights that he could not restrain the foolish words that spontaneously burst from him; nor was it love for a woman which had reduced him to this state. (He had never been in love.) What made him cry and mutter disconnected words was love for himself--a young, burning love filled with hope, a love for all that was good within his soul (and he felt at this moment that everything within his soul was good). Olenin had not studied anywhere, was not employed anywhere (except for some nominal appearances he put in at an office), had already squandered half his fortune, and though he was twenty-four had not yet chosen a career or done anything in life. He was what Moscow society calls "a young man."

At eighteen, Olenin had been free as only the rich, parentless young of Russia's eighteen forties could be. He had neither moral nor physical fetters. He could do anything he wanted. He had no family, no fatherland, no faith, and wanted for nothing. He believed in nothing and followed nothing. And yet he was far from being a dry, bored, or somber young man. Quite the contrary. He was fascinated by everything. He decided that love did not exist, but whenever he happened to be in the presence of an attractive young woman, he found himself rooted to the spot. He had always been of the opinion that honors and titles were nonsense, and yet had felt an involuntary pleasure when Prince Sergei walked up to him at a ball and spoke a few pleasant words. He gave himself up to all his passions, but only to the extent that they did not bind him. The instant he immersed himself in a certain activity and felt the imminence of a struggle, the tiresome struggle of everyday life, he instinctively hurried to tear himself away and reassert his freedom. This was how he had approached work, society, dabbling in agriculture, music (which for a while he had thought of devoting himself to), and even the love of women, in which he did not believe. He thought a great deal about where he should direct the power of youth that is granted a man only once in a lifetime. Not the power of mind, spirit, or education but the power to make of himself and of the whole world whatever he wants. Should he direct this power toward art, science, love, or toward some practical venture? There are people who lack this drive, who the moment they enter life slip their heads beneath the first yoke that comes their way and diligently toil beneath it to the end of their days. But Olenin was too aware of the presence of the all-powerful god of youth, the capacity to stake everything on a single aspiration, a single thought, the capacity to do what one sets out to do, the ability to dive headfirst into a bottomless abyss without knowing why or what for. He bore this awareness within him, was proud of it and unconsciously pleased with it. Until now he had loved only himself and could not do otherwise, because he expected nothing but good. He had not yet had time to be disappointed in himself. Now that he was leaving Moscow he was in that happy, youthful state of mind in which a young man, thinking of the mistakes he has committed, suddenly sees things in a different light--sees that those past mistakes were incidental and unimportant, that back then he had not wanted to live a good life but that now, as he was leaving Moscow, a new life was beginning in which there would be no such mistakes and no need for remorse. A life in which there would be nothing but happiness.

Copyright © 2004 by Leo Tolstoy. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.