Earth—Planet—Universe

John Muir is a man I would have loved to have met on the trail. I would have enjoyed walking with him through Tuolumne Meadows in his beloved Yosemite listening to him discuss each wildflower by name; tell stories of each peak he climbed and the weather on that day; what he saw and how he felt. I wonder if he would have ranted and raved or kindly addressed and advocated for these wildlands in his lifelong pursuit to protect them.

He might have said as he did in his essay, ‘‘The Wild Parks and Forest Reservations of the West,” published in his book,

Our National Parks: ‘‘Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, overcivilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life.”

And I would have agreed with him.

I like to imagine that he could walk with me now in the red rock desert of the Colorado Plateau where Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona share a common boundary point in what is known as the Four Corners. We would stand on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon in shared awe, where he once stood and proclaimed that it was ‘‘as if you had found it after death, on some other star; so incomparably lovely and grand and supreme is it above all the other can˜ons in our firemoulded, earthquake-shaken, rain-washed, wave-washed, river and glacier sculptured world.”

We might have discussed a wild life versus a domesticated one, and he would have exclaimed, ‘‘I have been too long wild” without any thought of changing his passionate stance toward the virtues of a life lived outside.

And then, I would have asked him to visit Big Flats outside of Moab, Utah, now a series of oil and gas drilling sites that look like monstrous, mechanical ravens with their heads rising up and down as they peck on carrion in the red sand on the edge of Canyonlands National Park, which now feels like an annex for the fossil fuel industry.

He might have expressed a longing for a reprieve in the cool alpine air of the Flathead Reserve, now Glacier National Park in Montana, where he said, ‘‘Give a month at least to this precious reserve. The time will not be taken from the sum of your life. Instead of shortening, it will indefinitely lengthen it and make you truly immortal.” And I would have had to describe to him that out of the some 150 glaciers visible during the seventy-six years of his life, a century after he’d left this Earth only 25 remain, and that glaciologists now predict the glaciers will be gone in fifteen years.

I would sit down with Mr. Muir in the shade of a juniper tree and speak of our warming planet, warming from an increased use of carbon through our excesses of driving cars, traveling by plane, and our societal and global dependence on coal, oil, and all manner of fossil fuels. We would speak of a population of billions and rising.

Perhaps he would inquire about water, being the citizen scientist he was, forever curious, always two steps ahead mentally, and say something to the effect of, ‘‘Oil is optional, water is not,” as the photographer Edward Burtynsky recently said after having spent a lifetime taking pictures of mined and spent landscapes, where toxins fan out at a river’s delta like a bloodred hand on the planet.

And then, I can envision we would time-travel back to Yosemite Valley during the days that Congress shut down the government, from October 1 to 16, 2013, because they could not agree on how to fund our national debt. During this dispute, our national parks were closed to the public. The lands rested. The deer and bears and hawks returned momentarily to the uncommon quiet of wild nature and to savor the silences. But the resourceful Muir would have found a way in, and we would have walked quietly, joyously up the trail to Vernal Falls and baptize ourselves once again into the Church of Awe and cleanse ourselves momentarily of grief. We would have sat very near the falls, wet from the ecstatic spray, and he would have recounted the time when he watched the moon through the veil of water as he braved his own annihilation just for the experience of standing behind the vertical torrent. Neither one of us would be able to tell if our tears were of joy or sadness, both of us knowing they spring from the same source: a love of beauty and all things wild.

What I would ask John Muir at that tender moment is, ‘‘When you wrote ‘John Muir–Earth–Planet–Universe’ inside the cover of your notebook, how did you know we were made of stardust? How did you understand a planetary consciousness when a hundred years later we are just beginning to comprehend your prescient words, ‘When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe?’ “

Donald Worster, the historian and author of

A Passion for Nature: The Life of John Muir, sees the Scottish-born naturalist’s legacy as a spiritual one. At a forum about Muir at Stanford University he said:

We should think about John Muir as the inventor of a new American religion. I don’t mean to put America in there exclusively, because people all over the world have responded to him . . . I think he is a religious prophet, and a lot of people in this country have followed him or followed those ideas . . . He’s important for the great work he did for getting our national parks and forests and wildlife refuges and wild places and beauty in our consciousness and concerned about saving them. I think he’s also important . . . as a kind of measuring stick for understanding where we were as a people and where we ought to be today . . .

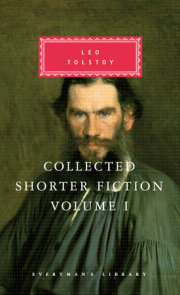

Consider me one of Muir’s followers, even disciples, of his wild joy, walking behind him on the path of wilderness protection. I am grateful that Everyman’s Library has chosen to publish this John Muir Reader in the nick of time.

*

When I was in college I worked at Sam Weller’s used bookstore in Salt Lake City, Utah. Sam knew I loved nature and nature writing. He took me aside one day after work.

“‘I want to show you something,” he said. We walked up the stairs into his office. ‘‘We just picked up a library from an estate sale. I thought you would appreciate this.” On his desk were eight volumes of a set of John Muir’s writings. ‘‘Two of the volumes are missing,” Sam said. ‘‘But you don’t come across things like this very often.” Always the businessman, Sam said, ‘‘I’ll give it to you for a good price.”

Sam’s ‘‘good price” meant I worked free for a month, but it was worth it to a budding naturalist who cherished Muir. Missing was a two-volume biography,

The Life and Letters of John Muir, byWilliam Frederic Bade (1923, 1924), which Sam helped me to locate.

This special ten-volume set was published by Houghton Mifflin in Boston between 1916 and 1924. They printed 750 sets. Ours was number #551. These books, bound in green buckram with brown leather patches bordered in gold glued to their spines that bear the name ‘‘JOHN MUIR,” were respectfully placed alongside Carson, Abbey, and Stegner. The first volume had a handwritten manuscript fragment glued to the first page before the title appeared: hence ‘‘The Manuscript Edition.” Muir’s own script, penned in sepia ink, read ‘‘learn that as these [landscapes] we now behold have succeeded those of the pre-glacial age, so they in turn are withering and vanishing to be succeeded by those yet unborn. The sun was wheeling far to the west when I began to seek a way home. I first scanned the western spurs.”

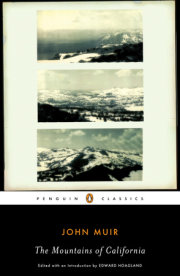

I found another version of these words again in Volume IV,

The Mountains of California, in chapter four describing Muir’s heroic (or ill-conceived) first ascent of Mount Ritter, 13,300 feet, in Yosemite.

As a young writer, I was fascinated to see how he had edited this snippet of writing. The word ‘‘landscapes” crossed out in pencil remained omitted in the final text. He substituted ‘‘those” for ‘‘others,” as in ‘‘others yet unborn.” And the last sentence in the final version of

The Mountains of California was greatly expanded, editing out ‘‘when I began to seek a way home.” The phrase, ‘‘the sun was wheeling far to the west” which began the original sentence found its new place in the middle of the polished construction: ‘‘But in the midst of these fine lessons and landscapes, I had to remember that the sun was wheeling far to the west, while a new way down the mountain had to be discovered to some point on the timber line where I could have a fire; for I had not even burdened myself with a coat.” The word ‘‘home” used in the fragment never appeared again. The last sentence of the manuscript fragment became the first phrase in the sentence that followed the expanded one: I first scanned the western spurs, hoping some way might appear through which I might reach the northern glacier, and cross its snout; or pass around the lake into which it flows, and thus strike my morning track.

The manuscript fragment glued inside John Muir’s collected works highlights both the Yosemite naturalist’s prowess as a gentleman mountaineer and his passion and verve for all things wild on the page and in the world. But it also showcases his sensitivity to language through his word choices, and these revisions showed his genuine skill as a writer. He taught me as a young writer that you can change your mind on the page—even change it often—until the right word appears and sticks. The process of revision is not only the cornerstone of good writing but smart living. For Muir, climbing Mount Ritter was also an exercise in revision. The path he planned and imagined taking was not the path he took. Nevertheless he did summit the peak.

[. . .]

Awe defines John Muir. Perhaps it began for him in 1863, sitting beneath a black locust tree on the Wisconsin University campus where he was a student. His friend Griswold showed him a flower from that tree and told him it belonged to the pea family. ‘‘But how can that be,” Muir recounted in

The Story of My Boyhood Home and Youth, ‘‘when the pea is a weak, clinging, straggling herb, and the locust is a big, thorny hardwood tree?” This insight stabbed deeply into Muir’s consciousness and changed the course of his life. ‘‘This fine lesson charmed me and sent me flying to the woods and meadows in wild enthusiasm.” Griswold’s ‘‘fine lesson” also injected him with a case of wanderlust rarely seen since. He walked a thousand miles from Indianapolis to the Gulf of Mexico. He sailed to Cuba and from there to Panama, where he crossed the isthmus and sailed up the west coast of the continent to San Francisco. He walked across the San Joaquin Valley and first glimpsed the ‘‘Mighty Sierra”:

Then it seemed to me the Sierra should be called not the Nevada or Snowy Range, but the Range of Light. And after ten years spent in the heart of it, rejoicing and wondering, bathing in its glorious floods of light, seeing the sunbursts of morning among the icy peaks, the noonday radiance on the trees and rocks and snow, the flush of the alpenglow, and a thousand dashing waterfalls with their marvelous abundance of irised spray, it still seems above all others the Range of Light.

Along with the locust and the pea, this journey opened wide the lens through which he experienced the world. Muir both believed in God’s creation and supported Darwin’s theory of evolution. ‘‘The awe with which Muir viewed every part of the natural world—floods and storms as much as anything else—was,” according to historian Terry Gifford in his book,

Reconnecting with John Muir, ‘‘intended in his writings to induce respect, humility, and, ultimately, conservation.” It became his bridge between seemingly opposing banks of thought. In the nineteenth century, the American West was on the verge of selling itself to the highest bidder, and I believe we stand at this threshold again today. Only, now, there is so much more at stake—the very health and wealth of the planet. John Muir and the community that surrounded him, including President Theodore Roosevelt, stopped this wholesale destruction of wild America through brave acts of conservation, be it the creation of the National Park Service or the importance of wild words on the page, which showed us that wilderness everywhere matters not only to the human spirit, but to life itself in all its evolutionary processes. We are not the only species that lives and loves and breathes on this planet. Earth is terrain of transformation: dynamic, indifferent, and acutely personal. By that I mean a mountain stands its ground, regardless of whether we choose to approach it; but as John Muir has shown us repeatedly, if we do approach the mountain, it is we who are moved.

Awe, I believe, set Muir apart during his lifetime. Awe is his currency today.

May the words between these covers reach us now and inspire another generation to fall in love with wild nature, to care for it, to know that wilderness is not optional but central to our survival in the centuries to come. May Muir’s writing remind us how to embrace this beautiful, broken world once again with an open heart, especially in the midst of what we stand to lose as temperatures rise. And may the planetary consciousness John Muir found in all life—from the wonder of a pea plant to the grandeur of great rivers of ice, now receding glaciers—inspire us to engage in the great work of ecstatic observation, relentless wandering, and joyous-fierce actions on behalf of the Earth. May we use our own curiosity as a compass.

With this reader in hand, we have a map—John Muir walks with us.

Copyright © 2017 by Introduction by Terry Tempest Williams. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.