S C R O O G E:

A N I N T R O D U C T I O N

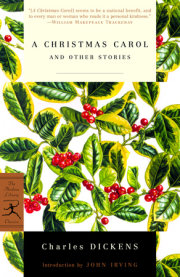

Charles Dickens wrote

A Christmas Carol in 1843, when he was thirty-one. He was already very famous, having made his name with

Pickwick Papers and then enhanced it with

Oliver Twist,

Nicholas Nickleby,

The Old Curiosity Shop and

Barnaby Rudge — and all this before he was thirty. This pace was prodigious. No writer alive had written at such a pace and produced such high-quality work at such a young age.

Dickens is said to have written

A Christmas Carol in six weeks, to pay off a debt—perhaps that was why grasping moneylenders were much on his mind—and he presented this novella as a light-hearted jeu d’esprit—a Christmas fairy tale or ghost story, intended to entertain, and to put his readers in good humour. The story has the traditional three-part structure of a fairy tale—three Spirits of Christmas, three ages of Scrooge—past, present, future—and it has also a fairy-tale ending, in which light triumphs over darkness, goodness and harmony reign, and an innocent life in peril—Tiny Tim’s—is saved, not to mention the gnarly old soul of Scrooge.

Dickens’s more covert intention—signalled by the work’s one-time working title, ‘The Sledgehammer'—was to strike a few more blows for the social justice he was so keen on by contrasting avarice and poverty, then proposing his usual antidote: an outflowing of private benevolence. For, as George Orwell has commented, though Dickens burned with anger at social injustices, he never went so far as to urge a wholesale political revolution.

But none of this would account for the overwhelming longevity and popularity of the Carol ’s protagonist—Ebenezer Scrooge. Scrooge is one of those characters—like Hamlet—who has become detached from the story in which he had his birth, and has become instantly recognizable, even by those who may never have read the book.

Why should that be? Let me consult my own model of that favourite Dickensian respository of infallible knowledge, ‘The Human Heart’. When did I first meet the immortal Scrooge, and why did I become so fond of him? I seem always to have been aware of him. Did I hear A

Christmas Carol read on the radio during my 1940s childhood? It’s likely—those were radio days. Or did I encounter him the way I encountered so much else—peering out with sly and narrow but nonetheless twinkling eyes from the colourful ads in magazines? In this respect, Scrooge was a sort of anti-Santa Claus—Santa Claus’s dark twin. The one, fat and jolly and round and red, dispensing largesse; the other, skinny and pinched and dour, withholding it. Yet at the end of the Carol, the new, redeemed, turkeypurchasing, Bob Cratchit-salary-raising Scrooge has become a sort of Santa; which raises the chilling possibility that Santa might one day shrivel and wizen, and morph into Scrooge at his worst—that crabby geezer who opens the book. Consider those punitive Santean lumps of coal—not much mentioned these days, but kept, you can bet, in Santa’s worst-case reserve arsenal of dirty tricks. Coal in your stocking would be just what the mean version of Scrooge would have liked.

Whatever the case, by the time my seven-year-old self discovered Scrooge’s descendant living in comic books in the form of Walt Disney’s Scrooge McDuck—Donald Duck’s crusty, miserly, rich old uncle— knew quite well what the name‘Scrooge’ was supposed to signify. It included the fact that within McDuck’s ancient, scheming husk there flickered a kindly and generous impulse. It was a good sign that the Duck triplets adored their Uncle Scrooge, and not only because he let them roll around in his money-bin full of gold coins: no, he was a lot of fun, because in recreational moments he often behaved just as childishly as they did themselves.

This is one key to the original Ebenezer Scrooge: he’s a child at heart. But, when we first meet him in

A Christmas Carol, he’s a wounded child, albeit an elderly one. In writing Scrooge, Dickens delved deep within, and put a good measure of his own hidden pain into his creation. He had never forgotten the most hopeless period of his life, when his feckless father had been locked into debtors’ prison, and young Charles had been wrenched from school and set to work in a blacking factory to help support the destitute Dickens family. This period did not last for ever, but for a child the present moment is for ever: the young Dickens could see no possibility of rescue from the unfamiliar hell into which his father’s financial mishaps had thrust him.

The most poignant moment in

A Christmas Carol is not the death of Tiny Tim, weep-making though that is; nor is it the plangent picture of Scrooge’s own possible future corpse,‘plundered and bereft, unwatched, unwept, uncared for’. (The objective mind might comment that it doesn’t much matter to a corpse what sort of outfit it’s wearing or who is standing around it, though it mattered a lot to Dickens.) No, the most sniffle-making scene is the first picture the Spirit of Christmas Past shows to Scrooge: his young boy self, ‘a solitary child, abandoned by his friends’ at a cheerless, run-down boarding school, while everyone else has gone home for Christmas. Luckily this child Scrooge does have some friends, but they are imaginary ones—they exist only in books. However, by the next picture— several years later—even these friends have gone, and despair has taken their place.

To be alone—to be a helpless child, neglected and forgotten, in a dreary place—such is the Dickensian nightmare acted out by Scrooge. It’s this, not the arrival of Scrooge’s sister Fan to take him home from school, nor the happy dancing and capering that goes on during Scrooge’s apprentice years at Mr. Fezziwig’s, that sets the miserly part of Scrooge on the road it has followed into old age. Scrooge’s famous cry of ‘Bah! Humbug!' means, ‘I won’t even admit the possibility of human sharing and happiness, because they were denied to me in the most important period of my life.’ The idea that Christmas open-heartedness and brotherly love are frauds had ample proofs in the childhood of Scrooge, and even to some extent in that of Dickens. For ‘sordid school’, read ‘blacking factory’. For ‘uncaring father neglecting his son’, read ‘imprisoned father whose lack of money caused the son’s ordeal’. Scrooge’s heart withered on the vine because Dickens’s almost did.

Due to the blacking factory episode, Dickens seems to have been torn throughout his life between two impulses—the fear of going bankrupt, which drove him to work himself into afrenzy in order to make more money; and the desire to exercise, himself, the generosity that would have saved his child self from the blacking factory, had anyone turned up with some of it then. In many of his fictions, Dickens is fond of arranging characters in pairs. The look-alikes Charles Darnay and Sidney Carton of A

Tale of Two Cities are the most obvious examples: the virtuous idealist versus the cynic and wastrel. We find such arrangements melodramatic: heroes and villains no longer convince us. However, in Ebenezer Scrooge, Dickens melds the two opposites into one. Being neither hero nor villain, Scrooge is both, and also an individual whose conflicts we can understand. Perhaps this is a clue to Scrooge’s long life, and to the popularity he still enjoys: with Scrooge, we don’t have to choose. Not only that, the two halves of Scrooge correspond to our own two money-related impulses: rake in the cash and keep it all for yourself, or share with others. With Scrooge, we can—vicariously—do both.

There’s yet another of those young-Dickens hapless-child avatars in

A Christmas Carol: Tiny Tim. Some people find wee Tim far too cloying to take straight: he’s so infernally good. But when the Victorians said, ‘He’s too good for this world’—which they often did— the kind of goodness they intended was a passivity due to illness: such children usually died early. Having already written the death of Little Nell in

The Old Curiosity Shop —to international mass wailing, and, according to the author, with the tears coursing down his cheeks as he polished her off —Dickens was well up to the pathos needed for the shorter and more indirect dispatch of Tim. But Tim is a boy who can be rescued, as Scrooge was not—or not until it was rather too late—and Scrooge himself can do the rescuing. He can perform for Tim the act of generosity that would once have saved his child self ; he can become ‘a second father’—the benevolent, competent, and financially sound father-figure he himself never had, and that Charles Dickens so frequently invented.

At the end of

A Christmas Carol, when all three Spirits have come and gone, and Scrooge has had a good repentant cry—always a positive sign, in the Dickensian world—and Christmas morning has dawned, and all the bells are ringing, and Scrooge has discovered he isn’t dead after all, he declares that he is not only as happy as an angel, he’s also as merry as a schoolboy. Now which schoolboy might that be? Certainly not the one Scrooge himself was, left alone and abandoned and despairing in the chilly, dank school of his youth. Rather the merry schoolboy he ought to have been, and that he can now be vicariously through Tim.

Our age is one that avoids mention of the salvation of souls, preferring to speak instead of Delayed Mastery and the Healing Process, and perhaps this is how we can best make sense of Scrooge. But whatever the terms of our interpretations, Scrooge has passed the only real test for a literary character: he remains fresh and vital. ‘Scrooge Lives!’ we might write on our T-shirts. Yes, he does, and we rejoice with him.

Margaret Atwood

Copyright © 1986 by Charles Dickens. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.