A Q&A Sarah Rose Cavanagh

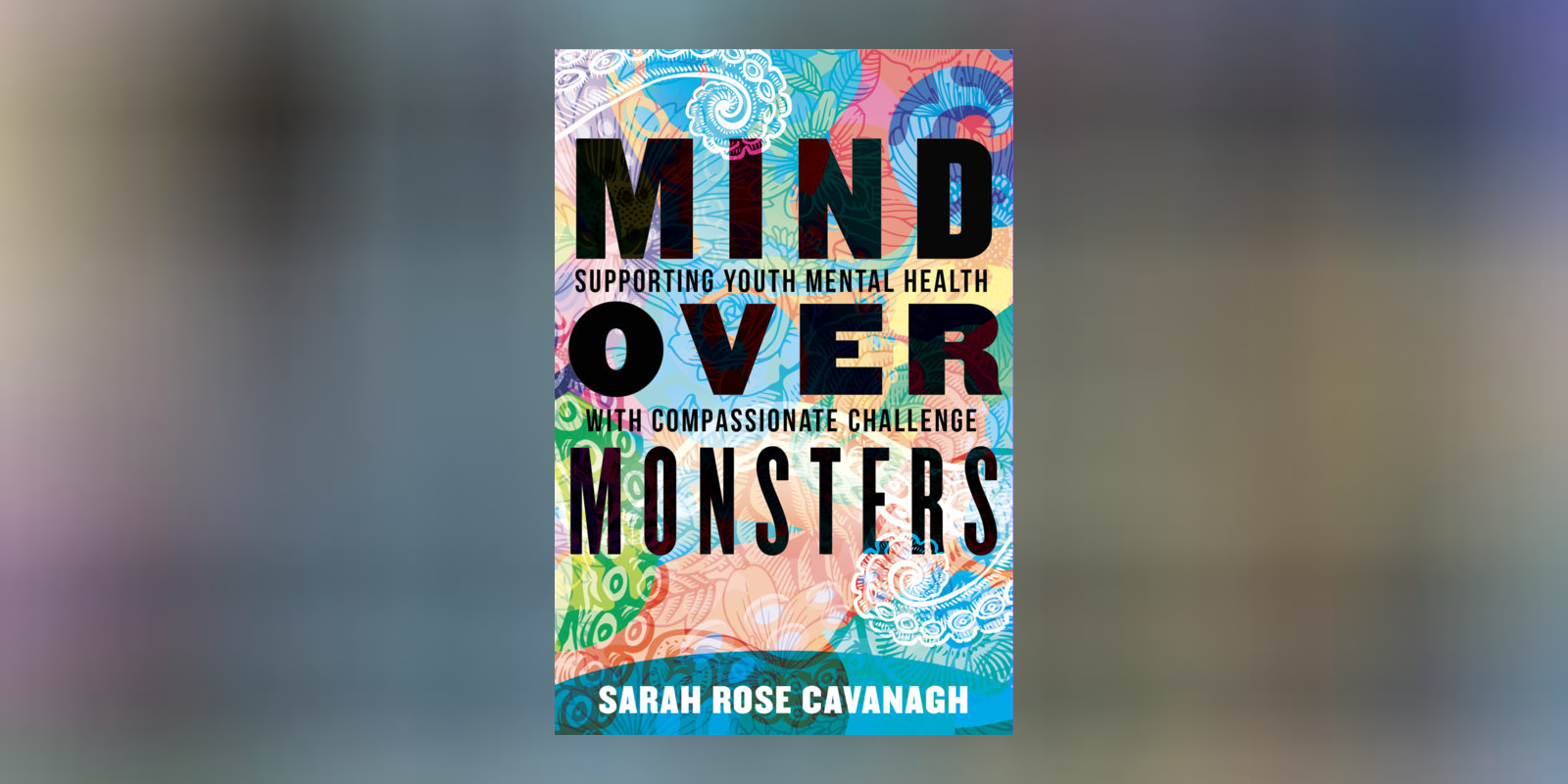

Statistics indicate that mental health problems like depression and anxiety have been skyrocketing among youth in recent years. The widespread isolation and disrupted learning during the pandemic years has only accelerated this crisis. The ever-present question today is, what changes can be made to educational settings in the US to better support youth mental health? As psychologist and professor Sarah Rose Cavanagh writes, our youngest generations are running “low on hope and high on burnout.” In Mind over Monsters: Supporting Youth Mental Health with Compassionate Challenge, Cavanagh examines how to create learning and living environments characterized by compassion, while guiding youth with practices that encourage challenge. Additionally, Cavanaugh shares her personal journey with anxiety, bringing a unique understanding to her exploration of the student mental health crisis. Beacon Press senior publicist Bev Rivero caught up with her to chat about it.

Bev Rivero: What inspired you to write this book?

Sarah Rose Cavanagh: I was drawn into this topic for a few different reasons. First, I was watching the news and reading articles warning about a growing mental health crisis in our youth—and this was even before the beginning of the pandemic. As a college educator who studies psychology, and as the parent of a teenager, this news was of high concern to me, both personally and professionally. Second, I was observing these battles taking place in higher education, where one side argues that youth need more compassion, care, and flexibility, and the other side says that we’ve already given too much, and that young people need more challenge, exposure, and risk-taking. I think if you put these people in a room together, most of them would find that really, they all agree that students need both compassion and challenge—but we end up having opposing conversations on opposite tracks. I want to open a conversation about the intersection of compassion and challenge.

BR: Your subtitle argues that we should support youth mental health with “compassionate challenge.” Can you explain what that is?

SRC: The take-home message of compassionate challenge is that we need to face the things that scare us, but the only successful route to doing so begins with a secure base. Life is terrifying, and monsters are real—the world is a dangerous place. We can’t stop being scared, but the best way to face those monsters is together, through the development of safety and belongingness and community. We have to do things we don’t enjoy to fix the problems in the world. Only by engaging with those problems can we solve them.

The monsters referred to in the book are both internal and external. I often view my own panic disorder as a sort of monster that afflicts me sometimes. Of course, external monsters also exist. Racism, poverty, gun violence, and climate change are quite real threats in the world. Internal threats often require more of a taming, involving approach and even befriending. External threats often require collective action, rooting out their sources and finding new solutions. In both cases, facing these monsters head on rather than hoping they’ll disappear on their own is the most productive approach.

BR: Compassion and challenge working hand in hand takes many forms in Mind over Monsters. What are some highlights that stand out that you encountered when gathering examples for the book, that either made it into the book or didn’t?

SRC: In terms of examples, I was most inspired by stories from students themselves about how they rose to challenges in settings of compassion. I recall one student I call Hannah, who as a first-year student at an HBCU completely froze in the middle of a class presentation. Rather than excusing her from finishing the presentation, her instructor calmly and supportively talked her through the rest of the talk. Hannah shared that this one experience not only changed her willingness to be a discussion leader in future classes but also made her much more comfortable in social settings on campus. She identifies that particular moment as a key experience in her development as not just a student but a human being in the world. And Stephen, who was in and out of the community college system in between some prison stays, who got so frustrated in a math class that he left his class and punched a tree and decided he was done with college. His math instructor followed him out and talked him into believing in his own possibility and returning. Or Krystan, who struggled to believe she could succeed in her college education and career given the challenges of her disability, who suddenly believed in her own potential when her psychology professor who happened to be blind told her that she inspired him.

These are all examples of students rising to challenge because they were embedded in situations where their autonomy, competence, and belongingness needs were met.

BR: You argue that youth need compassionate challenge and that motivation is served by shoring up young people’s feelings of autonomy, competence, and belongingness. Are there some ways to bring this into the classroom for young adults that come to mind?

SRC: Anxiety and motivation use many of the same physiological systems to mobilize the body for action. Changing the appraisal and interpretation of the challenges before us can spin us either toward motivation or anxiety.

Avoiding what you fear just reinforces that fear and can spiral into avoiding settings that are less and less challenging, narrowing the scope of your experience. Learning, after all, requires a certain amount of emotion and a certain amount of arousal. If students feel safe, have a sense of autonomy, and a sense of freedom in the classroom, this will help them feel capable, confident, and have a sense of purpose and vocation. These sorts of appraisals and settings can set them on a path to motivation instead of anxiety.

In terms of what compassionate challenge and support for motivation looks like in the classroom, instructors must do the compassion piece first. Ideally, the stage for compassion is set in the first few weeks of the semester. Compassion can be embedded into the atmosphere, the setting, and the syllabus. Instructors should establish the classroom as a space for co-creating and for discussion, and they should prioritize the building of relationships. Everyone hates ice breakers, but carefully used and well selected ice breakers can be great. They help to establish that we are a group of people working together in order to achieve a goal.

The challenge piece prioritizes student engagement, evokes their passion and curiosity, and motivates them to take risks. It also has a lot to do with a sense of play, in techniques that I call improvisational learning. We can take a lot of lessons from performing arts: the students and instructors work together as an ensemble, encouraging each other on to a shared experience of success. But the work often involves vulnerability, stretching past your comfort zone, and taking risks. When you can infuse the class with that sense of lightheartedness, intellectual play, and the sense that learning is fun, you can stimulate engagement and challenge your students to greater heights of learning. You also can ask more of your students, cultivating high standards and expectations.

BR: You write, “COVID took an already maxed-out industry and poured an avalanche of new need on top of it.” Are there any illuminating thoughts you’ve heard from mental health practitioners on a way forward, for a person seeking treatment or otherwise?

SRC: Well, from the societal side, we need a lot more mental health research and funding, particularly for adolescents. We also desperately need more clinicians of every sort. There is an enormous shortage of trained helpers, and sharply increasing need. More and more clients are seeking clinicians who can relate to their lived experiences, and the field of clinical psychology is overwhelmingly white and homogeneous in many other identity characteristics. And so, we also need targeted recruitment of and incentives for diverse professionals, particularly BIPOC professionals, to the field of mental health treatment. Even if we invest heavily in the expansion of mental health care services, it is unlikely to truly stem the tide of need we are seeing. To truly create change, we also need to explore and invest in community-based care, where we expand the amount of support people are receiving from their schools, their neighborhoods, their healthcare, their faith-based communities, etc. If we can support people before a crisis, we can reduce the strain on the mental health care system that was devised to respond to people in crisis. A big focus of the book is on the fabrics of care that support mental health—I think we could have a much huger impact on mental health if we addressed our fraying support networks than if we target treating symptoms once they emerge.

BR: When writing a book on mental health, particularly one that includes part of your personal journey with anxiety, what were some ways that you took care of yourself during the process?

SRC: I conducted the first interview for the book during the initial weeks of lockdown in spring 2020, and all of it was written in the ensuing years of disruption, higher ed pivoting to online learning, and remote schooling for my own child. I’m sure some of the darkness that lurks around the edges of the book seeped in from the global drama that was enfolding. But on the other hand, intellectualization has always been my primary emotion regulation method. Novelist Richard Russo once said that “one of the deepest purposes of intellectual sophistication is to provide distance between us and our most disturbing personal truths and gnawing fears.” So, bizarrely, writing a book about the psychological, philosophic, and neuroscientific basis of my personal journey with anxiety during an incredibly anxious time was probably, in fact, quite therapeutic!

But I also spent a lot of time cooking, romping with my dogs, and reading speculative fiction.

About Sarah Rose Cavanagh

Sarah Rose Cavanagh is the senior associate director for teaching and learning at the Center for Faculty Excellence and an associate professor of practice in psychology at Simmons University. Her research considers whether the strategies people choose to regulate their emotions and the degree to which they successfully accomplish this regulation can predict trajectories of psychological functioning over time. Her books include The Spark of Learning: Energizing the College Classroom with the Science of Emotion and HIVEMIND: The New Science of Tribalism in Our Divided World. Connect with her on Twitter @SaRoseCav.