Excerpted from the Introduction

INTRODUCTION

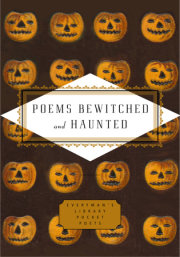

ONE FOOT OUT OF THE GRAVE

One moment you are alive. A car accident, a piece of pork stuck in your throat, or the slow burning away of disease, and then the change comes. The blood recedes. The heart silences. The breath dies out. Something shakes out of the body with the death rattle of that last breath. This transformation is the great mystery and the source of all religion. What is it that leaves? The spirit? The words for the soul – Latin

spiritus and Greek pneuma – mean ‘‘breath,’’ and it seemed to the ancients that breath carried that mysterious pneumatic spirit that animates the body. But the moment of death isn’t the story’s end. Horribly, the dead body swells and farts and shifts, and the hair and nails grow after death. From such phenomena, the ancients must have asked, can the same breath that carries the spirit away carry something back into the corpse? Whether this something is infection or demon, this possession and dispossession is the great fear at the core of many monster tales. Can the dead become undead?

Can they indeed come back like Orpheus and Odysseus and Lazarus? Sometimes the dead are said to come back in nightmares, remnants of nature that have been suppressed, and sometimes for revenge; other times when the dead return from their descent into the earth they are (like Persephone and Inanna and Jesus) figures of the famous resurrection stories in which the planted body is actually a seed that will sprout new life.

Zombies

At times, we call the resurrected

zombies. They are the children of sin, the dead bursting from their caskets in the end times; or they are children of the laboratory, mothered by infections or suffering contamination in an age ofHIV/AIDS and biological and chemical warfare. They come to us, things in the dark animated with unlife, and seem not to have souls, just an endless hunger to fill the emptiness inside with our tender flesh.

Fear often drives the creation of zombie tales, and of all monster tales, for that matter. What are monsters but

the unknown made flesh? They are the bad unknown, bad because the word ‘‘monster’’ comes from the Latin word for ‘‘warn’’ (

monere). We see in the poems of this collection the evolution of unknowns, dark figures in the family of archetypes that merit warnings. Therein lies their moniker

Monster. And yet, the literary creation of these monsters can be a coming to terms with or a safe rehearsal of fear, as horror author Stephen King has said. Monster creators facilitate the escape from the world’s crises and from ‘‘the cult ofconsciousness’’ into mythologies and ‘‘speculations of a fantasy world,’’ according to psychologist James Hillman.

In recent depictions, zombies move faster and faster, maybe because we humans have become more and more driven in pursuit of the possible. Humans hunger more than ever – for information, for physical satisfaction, for fame. Zombies are hunger at a cellular level. Suppressed hunger. Cannibalistic hunger.

Yet zombies are horrible enough moving slowly, with their failing body parts falling off around them. They move beyond death perhaps because (as in Bryan Dietrich’s ‘‘Zombies’’) ‘‘Hell / is full,’’ or as in Kim Addonizio’s poem ‘‘Night of the Living, Night of the Dead’’ because life itself is Hell they become zombies rising from their graves and stumbling up the hill toward the house. Thus, Addonizio winks at the reader and lets us know that these zombies are not so different from us: they are ‘‘like drunks headed home from the bar’’ and maybe all they want is to lie down in their drunkenness in some room while the world whirls around them, not to eat our brains after all. Maybe, in fact, the poem is really about human beings in such despair that they drink themselves into a state where they are mumbling, stumbling monsters, not unlike zombies?

In popular culture, the zombies represent different things in different generations: conformity and mind control in the Cold War era; or a disease metaphor in the era of AIDS. For Addonizio, they represent a relentless despair and self-hatred manifested in repeated self- destructive action.

Vampires

In England, it was common well into the nineteenth century to tie the feet of the dead to keep them from walking. Like zombies,

vampires are the walking dead, post-humans powered by post-human desire that makes the recognizable human form

sinister, as in Conrad Aiken’s seductress vampire, with her ‘‘basilisk eyes’’ and ‘‘mouth so sweet, so poisonous,’’ or that of Baudelaire, whose beauty is so great that angels would be damned for her, but who transforms after ‘‘she had sucked the marrow from [his] bones’’ into ‘‘a kind of slimy wine- skin brimming with pus!’’

We can look at ourselves as monsters and see how deeply we desire those things that quench our human, physical needs. We want to live longer; we want to eat more, kiss more, and how manipulative we can be in pursuing what we desire! Vampires are the embodiment of excess, and they, too, arise from and fall prey to infection, contamination, excess, as we see in Michael Hulse’s playfully ironic song/poem ‘‘The Death of Dracula’’: ‘‘The fiend who bled a thousand maids / has joined the dark Satanic shades.’’

Ghosts

But what if we die and our bodies decay, unreanimated, and yet we do still not go away? Then we are yet another monster, a

ghost. Perhaps we are the residue of human ineffable sadness, wafting in the room like the scent of flowers long turned to dust.

Ghosts are our largest pool of poems to consider, probably because ghosts are the monsters of reflection. They do not frighten us because they are exaggerations of ourselves the way that zombies and vampires are. They frighten us in apparition because they ask us to remember our own coming deaths and commit us to live, ‘‘Because, once looked at lit / By the cold reflections of the dead / . . . Our lives have never seemed more full, more real, / Nor the full moon more quick to chill’’ (James Merrill, ‘‘Voices from the Other World’’). And they remind us that they are out

there always reminding us.

Ghost settings, such as the Romantic graveyard of Wordsworth’s poem, ‘‘We Are Seven,’’ are as important in Gothic literature as the ghosts themselves. Tradi- tionally, particularly in America, houses and castles are haunted, as in Robert Frost’s chilling poem ‘‘Ghost House,’’ but when the

brain is haunted, the result is more unsettling. We can find this kind of haunting in Emily Dickinson’s ‘‘One need not be a Chamber – to be Haunted,’’ wherein the haunted body ‘‘borrows a Revolver’’ and ‘‘bolts the Door.’’ And although neuropsychologist Oliver Sacks has recently described ‘‘the feeling of someone standing behind you’’ as a neuro- logical phenomenon, Thomas Hardy’s poem ‘‘The Shadow on the Stone’’ puts a ghost to that feeling.

Copyright © 2014 by Tony Barnstone and Michelle Mitchell-Foust. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.