By Kristopher Jansma

We’ve all been there. We’ve worked for months, or even years, on a book… poured our hearts and souls into those chapters and characters, only to wind up having to walk away in the end.

Maybe you queried agents and got no takers. Maybe the publishers didn’t bite. Or maybe you simply decided the finished book simply wasn’t what you’d wanted it to be and you decided to move on. It’s hard, even heartbreaking. I’ve known writers who’ve never gotten over the disappointment of it.

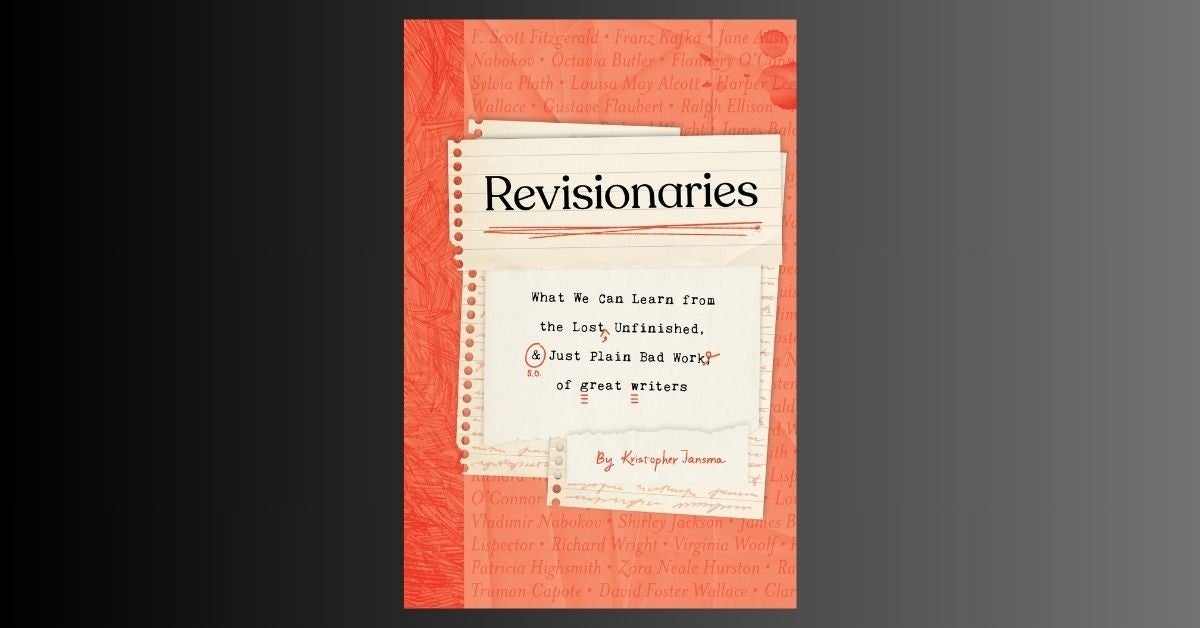

I’m here to say that you’re not alone. This happens to all of us, often many times in our writing lives—at least three times so far in mine. As I write about in my new book Revisionaries: What We Can Learn from the Lost, Unfinished, and Just Plain Bad Work of Great Writers, this has happened to some of the most remarkable, best, “genius” writers to ever live.

Jane Austen finished her novella, Lady Susan in 1794 and then decided to leave it in a drawer, even as it would take her seventeen more years to write Sense and Sensibility. Richard Wright, hot from his success with Native Son, got right to work on a book called The Man Who Lived Underground, only to have it turned down by his editor. And before Harper Lee wrote her masterpiece To Kill a Mockingbird, its characters and setting originally were conceived as part of an earlier manuscript (Go Set a Watchman) that editors turned down.

So, it happens to the best of us, literally.

But when it happens, what can we do? Usually we just reluctantly leave that book to collect dust in a storage unit, or to turn yellow in a desk drawer—but even a flawed novel, even a rejected manuscript… even a book we might be sick of and never want to think about again, deserves honoring.

You worked very hard to make something, and just because it won’t be on sale at Barnes & Noble anytime soon, doesn’t mean it should be lost and gone forever.

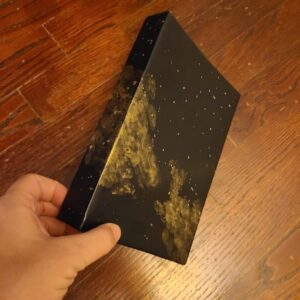

The first book I ever wrote was called August Asphalt. Nobody’s ever read it, aside from a few workshop classmates who mostly did not like it very much. By the time I finished it, I didn’t like it very much either. I was more than ready to move on to new ideas. But before I did that, I decided to make August Asphalt into a real book, just for myself.

To start, I reformatted the document in “booklet format”. Then I printed it out on my home printer in a ream of nice, off-white paper I bought at Staples, which felt more like that of a real book.

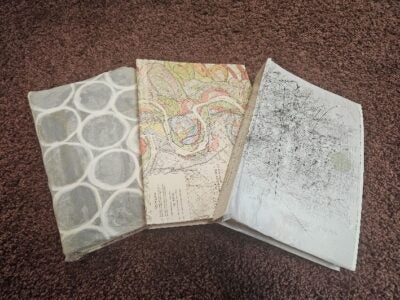

Then I followed some step-by-step instructions on how to bind the pages myself using some canvas and glue and cardboard and thread.

Finally, I drew (for better or for worse) a cover on the front with a gold pen. And I’d made the book that had existed only in my imagination real.

There are also plenty of places out there who will do something similar for you, usually costing hundreds of dollars, if not more. You can go that route if you like, but I will say that this whole project took a single afternoon and cost me less than $20.

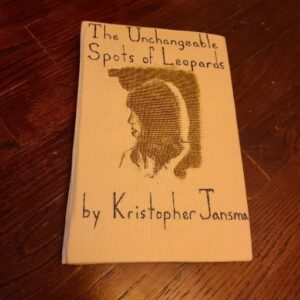

Eventually I wrote a new book, which would become my first published novel, The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards, but during the editorial process I ended up making several large changes to the structure of the book—changes I was happy to make, but at the same time I wanted some way to commemorate the original version.

So, I went back to the craft store and, a day or two later, had made myself a “Director’s Cut” edition of the novel that I could keep on my shelf right next to August Asphalt.

Back then I imagined that after publishing a real novel, I would never again face the struggle of writing a book that would eventually not make it out into the world. But it’s happened to me twice, and both times I was happy to be able to make some peace with the disappointment by going back to my book binding practice.

No matter what happens now, I have made this a way of closing the loop on any new long project. Before it goes off to see how it fares in the world, I make this one, perfect, personal copy for myself.

It’s a way to honor the idea of it, the work and the time. It’s a way of giving the book your dream treatment: the title you loved, the cover you dreamed of, and all the wild diagrams and endpapers you want.

Binding this one copy for myself has become an important way of separating the writing part of the process from the publishing part of the process. Our job is to write as well and truly as we possibly can. What happens next can be, unfortunately, entirely out of our hands. That’s why it’s become important to me to create at least one version of the book that lives wholly in that first realm, regardless of what life it may eventually have in the second. For $20 and an afternoon spent formatting and gluing, we can all honor our own “lost” books.

And who knows? Maybe someday some scholar like me will find them in an archive somewhere and eagerly begin to read. But until then, it’s enough that it be there just for you, as a reminder of what you accomplished and a way of beginning to move on to whatever even better thing will come next.

With students in my creative writing classes, I have had them submit a piece of work to be “published” in a similar manner, as part of a class literary magazine. This can be done with a simplified version of the same method: collect the class pieces and then use the Booklet printing feature again to create the pages that go inside the magazine. The class can either collaborate on a design for a cover, or each student could design their own edition, using original art, “zine”-style collage, or computer-generated images. These will be smaller and easier to bind together with a “long-reach” stapler (usually less than $10 at any office supply store or online). Alternatively, have each student take a longer work and bind/cover it, using these same techniques.

Kristopher Jansma is the author of the novels Our Narrow Hiding Places, Why We Came to the City, and The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards. He is the winner of the Sherwood Anderson Foundation Fiction Award, a Pushcart Prize, and the recipient of an honorable mention for the PEN/Hemingway Award. His short fiction, distinguished in The Best American Short Stories 2016, has been published in The Sun, Alaska Quarterly Review, Prairie Schooner, Story, ZYZZYVA, and elsewhere. Kristopher is an associate professor of English and director of the creative writing program at SUNY New Paltz College.