Love Is a HAUNTED HOUSE or, What Pride and Prejudice Would Look Like as a Horror Novel

We know (and Jane knew) that Austen’s classic romances are deeply influenced by the Gothic, by the horror and terror of late-eighteenth-century popular fiction. Because Jane Austen is such an influential figure in the history of the novel, romance from Austen onward is thus infused with the Gothic—it is full of horror or, at least, callbacks to the Gothic genre and reminders that danger lurks in the shadows of our everyday lives and loves.

What happens, then, if we read Pride and Prejudice as a scary story?

Now, before I lose the Darcy lovers: I’m not necessarily claiming that Pride and Prejudice actually is a scary story, or that we need to read it that way all the time. Far be it from me to claim special knowledge of Jane Austen’s intentions—that would be sacrilegious of me as an English professor! And there are, of course, important and satisfying takeaways that come when we read (and reread) Pride and Prejudice as a love story. Darcy shines as a romantic hero, and has become the basis for almost every romantic hero to follow, because he not only cuts a dashing figure but also recognizes and makes amends for his mistakes while resolving his past trauma, all in the service of forging an (at least emotionally) equal, consensual relationship with the smart girl. That’s hot, and I get it.

And yet. Not every taciturn asshole is Darcy in disguise, or Darcy before he meets his match. Not every beast in a castle will give you an amazing library and transform into a prince if you’re just, like, persistent. In other words, Darcy has given us some dangerous ideas. Whether you read Pride and Prejudice as ideal romance or as Gothic horror, it’s important to reckon with how the Darcy blueprint has messed up our expectations of romantic prospects (especially men), from rude strangers at parties to emotionally withholding partners— all while generally twisting our ideas about love. (Real quick: it’s not your job to fix anybody, and rude people at parties are often just jerks.) So whether you’re a goth ready to paint Pemberley black or a tried-and-true Jane Austen aficionado deeply resistant to the idea that Pride and Prejudice might offer anything other than just deserts and a sweet resolution, excavating the novel for its hidden darkness is an important exercise because it helps us uncover what is harmful about our shared ideas of romance.

Because in Jane Austen’s era—and in Pride and Prejudice—love is unquestionably scary for women. And by reading Pride and Prejudice for the danger that lurks at its margins, we can begin to understand what the danger in Austen’s classic means for us today.

To understand Pride and Prejudice as a scary story, we’re going to need to adjust our expectations. When we go in looking for an idealized marriage plot, the novel certainly delivers, because the genre contract formed between romance readers and romance authors is, in large part, derived from Pride and Prejudice. Whether or not you’ve read Pride and Prejudice before, if you’ve read or watched romance or romantic comedies, you’ve basically been trained to read it, and to pick up what it is (ostensibly) putting down. There’s the apparent bad boy who actually turns out to be a loyal and loving (and wealthy) hottie; the smart, relatable heroine who turns him down when he doesn’t yet deserve her; the slutty other woman who ends up with the sniveling jerk. The beautiful female friendship between Elizabeth Bennet and her sister Jane—which is probably a tribute to Jane Austen’s feelings about her own dear sister, Cassandra—functions as a restorative force that overcomes the bad and misguided behaviors of others and leads the sisters to happily ever after with the men of their choosing. In other words, if you’ve enjoyed any of the interrelated genres that take Pride and Prejudice as their touchstone, you are definitely going to like this book (or, at least, one of the many film adaptations).

But what happens if you come to Pride and Prejudice with another set of genre conventions in mind? By looking at Pride and Prejudice through the lens of horror tropes, we can begin to reveal its Gothic underbelly, and to notice the fear and danger that haunt the novel and its world.

Longbourn Is a Haunted House

From its opening pages, Pride and Prejudice is set in a haunted house— even though the specter that’s haunting it has to do with a death that hasn’t happened yet. Lizzy and her sisters are growing up in a home they will lose the moment their father dies. They’ll also lose the income that comes with their property, meaning they’ll be completely dependent on their friends and relatives for survival—unless they marry well. Their father—taciturn, affectionate, mocking, distant, clever but not wise—is a ghost in the machine, his life the only thing blocking their fall from respectable comfort to quiet desperation. They must find love because Mr. Bennet will die. Only romance can vanquish the ghost.

This threatening state of affairs might be Mr. Bennet’s fault, either because he refuses to stand up to social and familial pressure to contest this legal arrangement or because he himself is responsible for the arrangement in the first place. In any case, Mr. Bennet is dismissive of his wife’s fears to the point of cruelty, once even stating that he hopes she dies first. Whether he’s legally inept or knowingly damning his daughters to destitution, Mr. Bennet certainly has a touch of the sadist about him.

But if he’s bad now, Mr. Bennet’s legacy will be even worse, and this grim future attends his girls from birth, a lurking presence, something in the air. What is that bump in the night, that quiet murmur coming from the library? It’s Mr. Bennet, and when he dies, his past will ruin us all.

Mrs. Bennet Is the Haunted House Historian

But is the entailment all Mr. Bennet’s fault—I mean, did Mr. Bennet take one look at his hot wife and gamble the estate, assuming they’d have a boy eventually? Or is this intergenerational sexism at play, a long-standing arrangement Mr. Bennet either refuses to stand up to or doesn’t realize he can undo? We don’t know. We won’t know. Only Mrs. Bennet knows. She is the haunted house historian, the character who knows the backstory, the one who understands how we wound up in this mess. The more she sounds the alarm, the more Mr. Bennet teases her—is it any wonder she feels like she’s going batty?

Mrs. Bennet is the haunted house historian and she is pissed. She has given her life, her body, her beauty to the project of having a boy. In so doing, she has also become an additional horror trope: the mother of monsters, spawning and neglecting creatures who will end up feeding off society if they can’t form a parasitic bond with the first eligible man who comes their way.

And what would it mean to save them, to save herself? Trapped between impenetrable legality and a husband who will barely look at her, desperate for her girls to survive on the marriage market with only their beauty and charm to recommend them, Mrs. Bennet finds herself squirming under the weight of heteropatriarchal capitalism. Is it any wonder she’s notoriously awkward? She’s a monster and a mother in a maze and she doesn’t know which way to turn.

Mr. Collins Is the Attack of the Monster Appendage

If the Bennet sisters are up against horrors of all kinds, from the prospect of economic and social ruin to the lure of seductive predators and the haunting injustices of the past, then Mr. Collins is a monstrous appendage, a talking head and grasping hand hoping to pick one of them off. First he goes for Jane (she is the prettiest one and must be punished), but he’s easily redirected toward Lizzy, and only by risking her life and future can our heroine avoid his cloying grasp.

Charlotte Lucas Is Living Another Person’s Nightmare

Lizzy’s BFF, Charlotte Lucas, is focused on her own survival. Without good looks or great fortune, she’s fighting for her life without a weapon, and has to game the system instead. Mr. Collins came to town for a wife and a wife he shall have, and it doesn’t take much to win him over. Soon Charlotte has a proposal, a comfortable home, and the promise of moving into Longbourn later.

But Mr. Collins’s company is so grating, Charlotte will need to set up her living quarters to avoid running into him. By trying to avoid the fate she expected, that of dying an old maid, Charlotte has yoked herself to a ridiculous, obsequious creature who can never understand her, truly love her, or be her equal. She’ll inherit her best friend’s house, sure, but she’s also living her best friend’s worst nightmare.

Jane Bennet Dwells in the Uncanny Valley

Jane Bennet is so lovely, so demure, so poised that the love of her life is easily convinced that she isn’t what she seems and doesn’t really care for him at all. She seems too good to be true, and her close-but-imperfect resemblance to a real girl (like Lizzy, who manages to keep it remarkably real considering the amount of pressure she’s under) arouses suspicion if not outright disgust in a reader—or a suitor, or a suitor’s nosy friend—who expects a little humanity.

She’s too pretty, too calm, too generous. She sees the best in everyone, always speaks with kindness, and means what she says. To survive in Regency England, women must be perfect. Just don’t be too perfect, or you’ll end up in the uncanny valley: not quite a hot girl, not quite an automaton, not quite a corpse.

Mary, Kitty, and Lydia Bennet Are the Weird Sisters

Given how badly Mr. and Mrs. Bennet wanted to have a son, it’s no surprise that daughters three through five were disappointments, and largely neglected. Taken as a trio, Mary, Kitty, and Lydia are the Weird Sisters of the story. They lurk in the background, at least for a while, but they are cooking up some disruptive magic that will send others’ expectations into a tailspin. There’s Mary, the crone, a nerdy autodidact with poor self-awareness. And then of course there’s Lydia, the maiden, a budding, naïve seductress whose sexual appeal and power will throw a wrench in her family’s plans. Once we have a maiden and a crone, all we need to complete the archetype is a blustering, anxious, doting mother. Oh, what’s that, Kitty? We forgot you were there.

Wickham Is the Bad Guy Who Wins

George Wickham is a serial predator who preys on fifteen-year-old girls. He’s a seductive monster, a child eater, a vampire looking to extract sex and wealth from his victims. And while he fails in his plot to hold Darcy’s sister for ransom, he ultimately gets his way, sleeping with Lydia out of wedlock and convincing her that his affection is genuine. When Lydia refuses to leave Wickham’s side—and who could blame her, given the life that awaits her as a “fallen woman”— Darcy pays Wickham to make the marriage official. In so doing, he may restore the Bennet family to their social graces and make his own intended marriage less of a blow to his brand. But he also lets the bad guy win.

Lydia Is the Bad Seed

What happens if from the moment a young girl is born, you teach her that her birth has doomed the whole family? As the last daughter, Lydia is the bad seed, the one who promises to destroy the family by the very nature of her birth. If she had been a boy, she could have saved them all, but because she is who she is, darkness promises to triumph. Neglected by her father, spoiled by her mother, and deemed useless from the start, Lydia, much like Frankenstein’s creature, must rely on overheard chatter to figure out how to be and what to do. (Is it any wonder she’s obsessed with gossip?) And the message is simple: only through marriage can you save yourself and the people who are supposed to love and care for you.

But the systems in place for finding a husband won’t work for Lydia. She’s the youngest, and not the prettiest, and she has no fortune to her name. Luckily she is also the tallest and has “high animal spirits”—she can embrace her monstrosity and take matters into her own hands. Leveraging her youth and her raw sexuality, she becomes an enfant terrible, a monstrous child, a dangerous flirt who will stop at nothing until she has imperiled herself and her family. But this peril is also her ticket out, a workaround, a blistering shortcut. By absconding with a monster, she makes herself a damsel in distress, and our “hero” has to rescue her. He does this by chaining her to her predator, sure, but we don’t know what happens after our beauty and her beast tie the knot.

Perhaps Lydia is buried alive, forever yoked to a man who does not and cannot love her. Perhaps she reminds us not to go in the woods, not to circumvent the places and spaces and roles we are expected to fill, because there are always creatures lurking in the shadows. Or maybe Lydia is a body of bodies, the conglomeration of all her family’s hopes, dreams, failures, and sins, a creature that cannot be contained by society and that will do anything in its power to break loose. Austen’s narrator tells us she lives an “unsettled life,” meaning she and Wickham move here and there, sometimes together, and sometimes apart, but I’m not sure I buy it. Maybe Lydia stays with Wickham, and maybe she takes off again.

Elizabeth Bennet Is the Final Girl

The marriage market is a dangerous game. Lizzy wins, and the rest of you can pack up and go home. If you have a home to go to, that is. Put another way, Lizzy is the final girl, the girl in a horror movie who—generally because of her moral righteousness—is allowed to live to the end, and even defeat the killer.

Remember the first time Lizzy spots Darcy? They’re at a ball where there aren’t enough men to keep the ladies busy on the dance floor. (England is at war with France and lots of men have gone off to kill or die.) Darcy isn’t dancing, and Lizzy isn’t dancing, but instead of asking Lizzy to dance, Darcy ignores and insults her. (Remember, he tells Bingley that it would be a “punishment” to dance with any of the available partners and says that Lizzy is “tolerable; but not handsome enough to tempt me.”)

This might seem like the end of their story, but Austen knows something we don’t know yet, something Lizzy will learn that will let her escape with her life and something the book will teach us and reteach us for generations. It’s no big deal if your soulmate overlooks you the first time he meets you. Disinterest and casual cruelty make a guy more interesting; the chase will be such fun!

In other words, if you want to make it out alive, you’d better learn to love a monster.

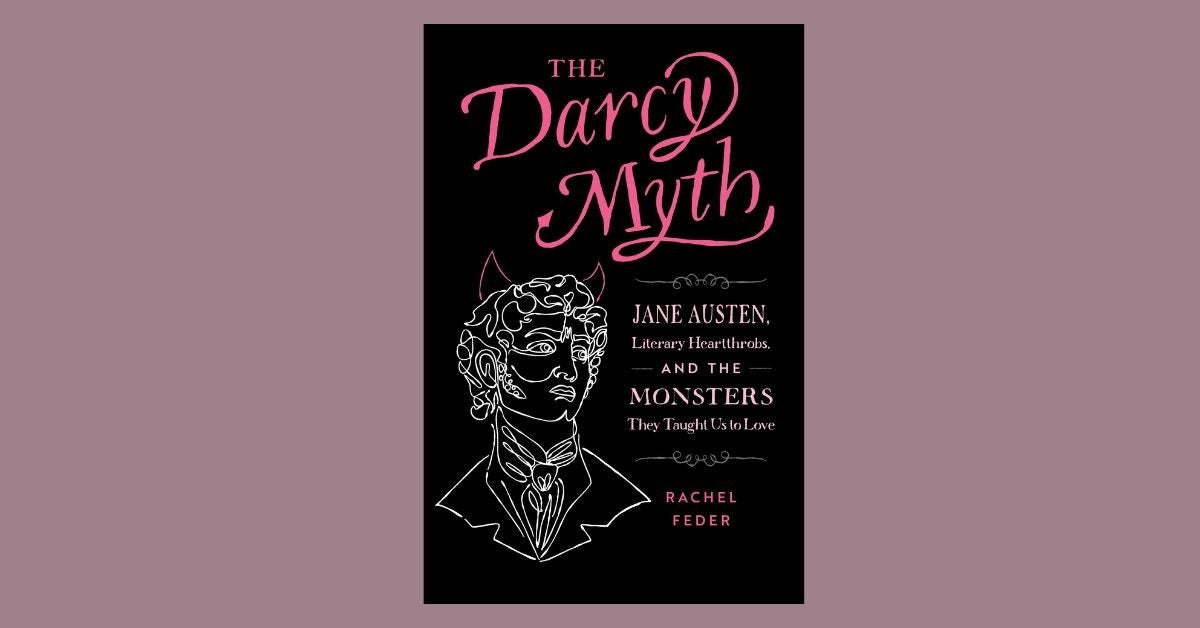

Excerpted from The Darcy Myth: Jane Austen, Literary Heartthrobs, and the Monsters They Taught Us to Love by Rachel Feder. Reprinted with permission from Quirk Books.

Rachel Feder is an associate professor of English and literary arts at the University of Denver, where she regularly ruins Pride and Prejudice for her students (but in a fun way!). Her work on the Gothic and nineteenth-century British literature includes the book Harvester of Hearts: Motherhood Under the Sign of Frankenstein and the Norton Library Edition of Dracula, which she edited. Her poetry and prose have appeared widely.