Stewardesses aren’t the first workers that come to mind when you think of the labor movement. But behind that smiling, compliant, conventionally attractive image lies a group of militant unionists who led an unheralded workplace revolution that changed American history.

In the beginning of the 1960s, the airplane cabin might have been the most sexist workplace in America. Women working as stewardesses (the switch to “flight attendant” wouldn’t come until men started being hired in significant numbers in the next decade) had to maintain slim figures, were weighed before they got on the plane, and couldn’t wear glasses. They had to remain unmarried, couldn’t have children, and were fired when they turned thirty-two (at a few airlines the deadline was extended to thirty-five).

By the end of the decade, thanks to a combination of lawsuits and bargaining, many of these strictures had been removed. Stewardesses had been some of the first to see how Title VII of the Civil Rights Act could be used to fight sex discrimination. They lodged hundreds of complaints with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and lawsuit after lawsuit. They turned Title VII into a weapon against discriminatory employers that would be used by countless others in the years to come, and established case law that benefited all working women. And it worked for them, too: by the early 1970s, flight attendants could get married, have children, age on the job, even wear the occasional pair of glasses (the weight limit debates are still going on). But, now that their job had become a career, their pay, benefits, and working conditions suddenly became more important.

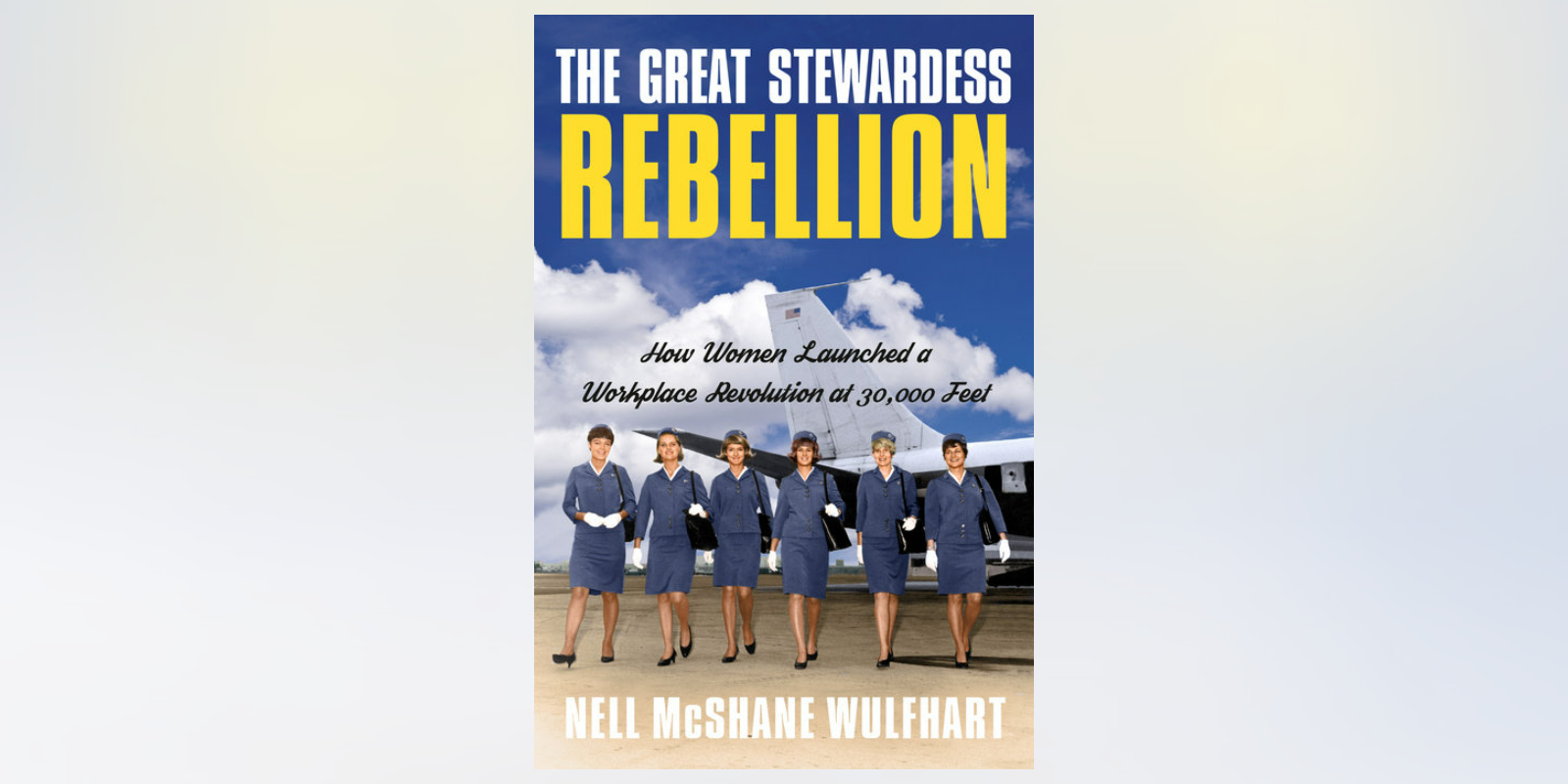

In the 1970s, they took on their own union. Stewardesses at nearly every airline had been unionized for decades. At many airlines, flight attendants were represented by the Transport Workers Union, which also represented mechanics, cleaners, and ground staff. But the women were pushed to the bottom of the priority list when it came to bargaining. The TWU would go all out to get raises, retirement benefits, and improved working conditions for the other—nearly all male—workers. When it came to helping the stewardesses, who made less money and had far stricter work rules (no one put a mechanic on the scale before starting his shift or insisted that a miniskirt was now a mandatory part of his uniform), the TWU dropped the ball. Women, they considered, weren’t really workers. But as the decade wore on, the stewardesses got more aggressive. They pushed the TWU to bargain for the things they wanted. One memorable example I discuss in my new book, The Great Stewardess Rebellion, was a showdown over single hotel rooms on layovers. Pilots got single rooms, as did male flight attendants, but the women always had to share. The TWU didn’t consider this something worth bargaining for, so the women took an unprecedented step: they voted down their contract twice before the TWU and American Airlines gave in.

These women grew more militant as the years went by, belying the image the airlines loved to promote in their ads—a youthful beauty whose smile never dropped, who was there to meet every possible passenger need, someone who was endlessly accommodating. They became steadily less accommodating, forcing the TWU again and again to bring their working conditions in line with those of male airline workers. And, when that took too long, some of them went rogue.

As I explore in the book, in the mid-1970s there was a sea change at the TWU. Thousands of flight attendants took the radical step of leaving the TWU entirely, and forming their own, women-led unions. Rather than be seen as the “mascots” of the labor movement, they decided to seize power for themselves. There were a few other women-led unions at the time, most notably 9 to 5, an organization of women clerical workers; they joined SEIU (the Service Employees International Union) in 1981. But these unions remained within the bounds of traditional labor organizations. The stewardesses went their own way. They decided change could come slowly, as they pushed the male TWU leaders to take them seriously, or it could come quickly—replacing those union leaders at the bargaining table with women straight out of the membership.

In less than three years, nearly every flight attendant in the United States had changed his or her (mostly her) union, with around 14,000 leaving the TWU. For an industry that had tried for so long to convince itself of women’s docility and to sell tickets based on the looks and sex appeal of their workers, this was a display of pure rebellion—unladylike behavior that was decidedly in conflict with the traditional image of a stewardess. Now, though she might have to wear a miniskirt, she’d be wearing it to the bargaining table.