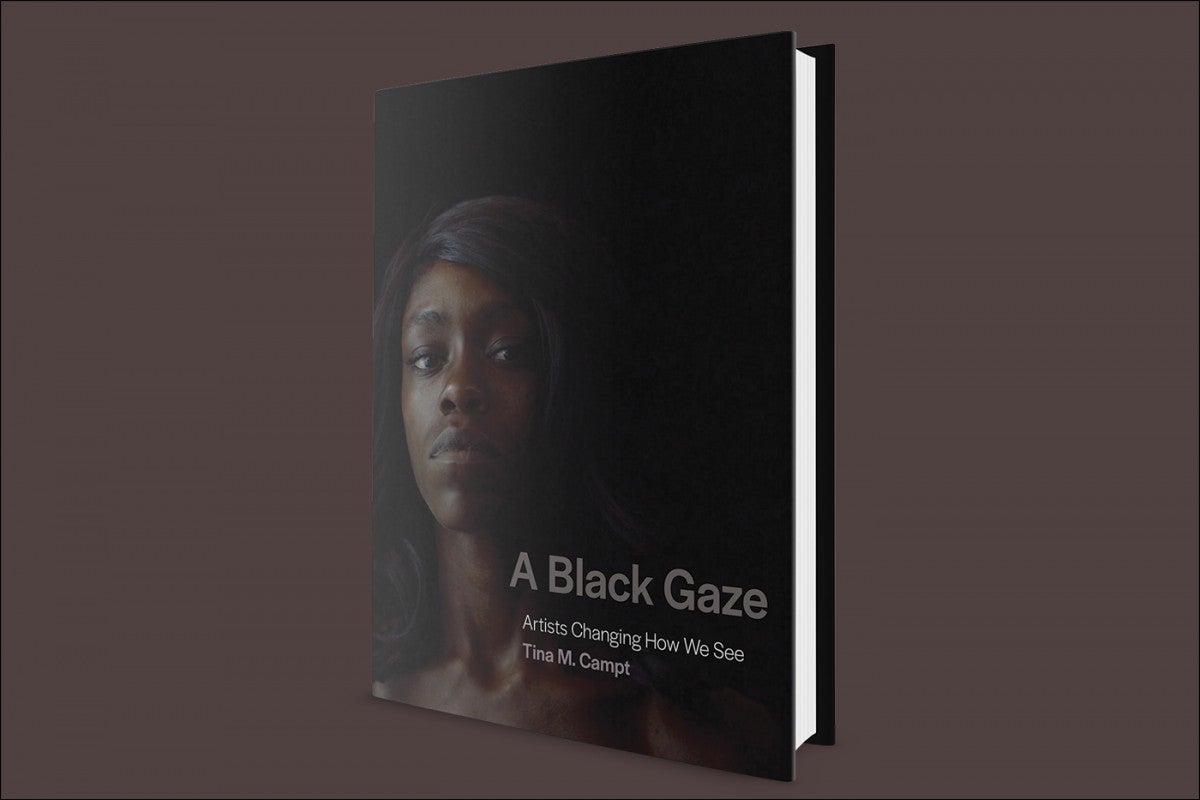

Last week, the MIT Press published A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See by Tina Campt, examining the work of contemporary Black artists who are dismantling the white gaze and demanding that we see—and see Blackness in particular—anew. Campt shows that this new way of seeing shifts viewers from the passive optics of “looking at” to the active struggle of looking with, through, and alongside the suffering, and joy, of Black life in the present.

Recently, Gabriela Bueno Gibbs and Victoria Hindley of our acquisitions team sat down to discuss the project, Campt’s innovative work, and their experiences editing the book. Read their conversation below and learn more about A Black Gaze.

Gabriela Bueno Gibbs: Tell us a little bit about how you found this project.

Victoria Hindley: I was introduced to theories on race and gender during my undergraduate studies, and I’ve been fortunate to focus on visual culture and design projects that examine these areas throughout my professional work. Two projects stand out as defining moments for me—a book with Nigerian Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka and an exhibition with South African photographer Zanele Muholi. These cumulative experiences showed me that there was another way of seeing that wasn’t always accounted for in our body of knowledge.

When I met Tina Campt in London at a conference in 2018, I was floored by her genius. It was the first time I’d heard someone speak about the much-theorized concept of the gaze in a wholly new way. It made sense of everything I’d been encountering but hadn’t seen published. I asked Tina to write for the Press. When her agent sent me the proposal for A Black Gaze, I knew it was the book I’d been seeking.

Gabriela Bueno Gibbs: If you had to pitch this book to someone who has never read an art or visual culture book but is interested in the topic, how would you do it?

Victoria Hindley: What I love about this book is Tina’s extraordinary ability to deliver difficult insights about systemic racism and the weight of Black precarity while simultaneously celebrating Black joy and achievement in spite of these burdens. She invites the reader to experience this reality through her lyrical, forthright, and compelling writer’s voice. I’d say: If you let it, this book will change you. It’s a gift.

What have you enjoyed most about working on the book, Gabi?

Gabriela Bueno Gibbs: This was one of my favorite books to work on, not only because it is an engaging and important contribution to decentering the white gaze in visual culture, but also because Tina’s writing is intentionally, and unapologetically, personal. This is clear throughout the text, and in the marginalia where she highlights definitions of terms and concepts of her own. Unlike the majority of academic work where the author removes themselves from their work, Tina takes us with her in her journey on developing the concept of a “Black gaze.” This is not a strategy to draw in the “general audience” that we aim to reach in trade titles, but an integral and central strategy to the work itself, and one that I wish scholars used more often. Tina does it beautifully, and the images are stunning, to boot.

Did you learn something new about your job as an acquisitions editor while working on this project?

Victoria Hindley: I love this question because I learn new things with every book. This project taught me that even though I’ve been working on race for decades, there is always so much more to learn—and that the work of comprehending my own position as a white person enculturated within systemic racism is a life’s work. It is both humbling and invigorating.

Gabriela Bueno Gibbs: What do you hope people will feel after reading A Black Gaze?

Victoria Hindley: I’d like people to feel this: “Wow, I’d never thought of my position as a viewer of Black life that way. Seeing, truly seeing, is a beautiful and empowering responsibility.”