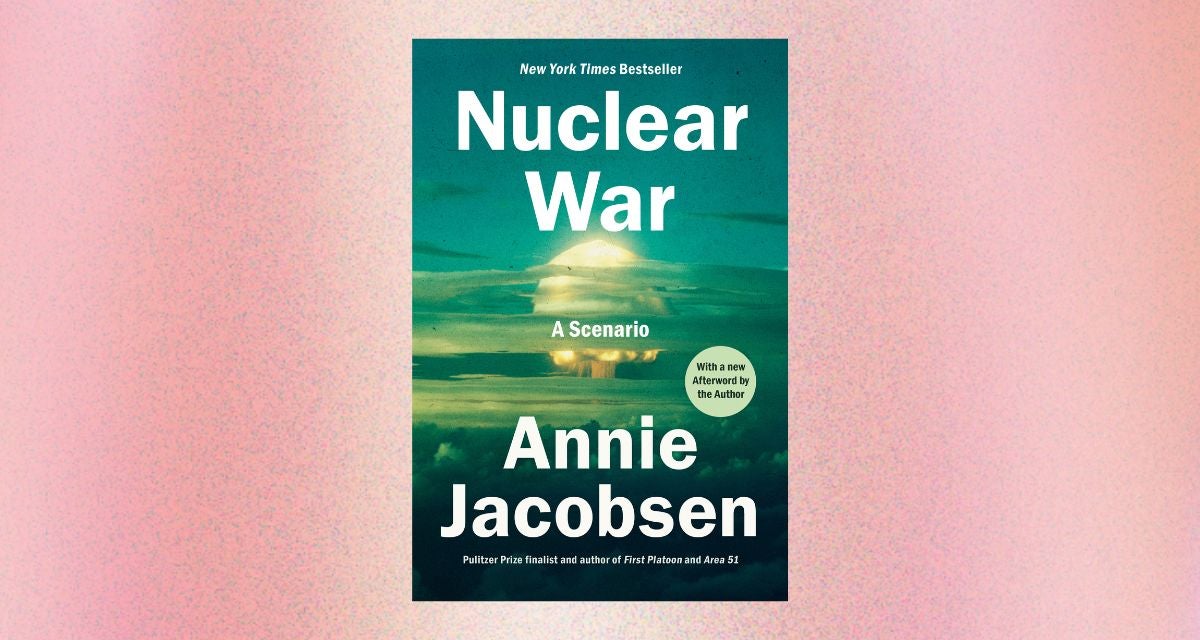

Pulitzer Prize finalist Annie Jacobsen’s Nuclear War: A Scenario explores this ticking-clock scenario, based on dozens of exclusive new interviews with military and civilian experts who have built the weapons, have been privy to the response plans, and have been responsible for those decisions should they have needed to be made. Nuclear War: A Scenario examines the handful of minutes after a nuclear missile launch. It is essential reading, and unlike any other book in its depth and urgency.

PROLOGUE

Hell on Earth

Washington, D.C.,

Possibly Sometime in the Near Future

A 1-megaton thermonuclear weapon detonation begins with a flash of light and heat so tremendous it is impossible for the human mind to comprehend. One hundred and eighty million degrees Fahrenheit is four or five times hotter than the temperature that occurs at the center of the Earth’s sun.

In the first fraction of a millisecond after this thermonuclear bomb strikes the Pentagon outside Washington, D.C., there is light. Soft X-ray light with a very short wavelength. The light superheats the surrounding air to millions of degrees, creating a massive fireball that expands at millions of miles per hour. Within a few seconds, this fireball increases to a diameter of a little more than a mile (5,700 feet across), its light and heat so intense that concrete surfaces explode, metal objects melt or evaporate, stone shatters, humans instantaneously convert into combusting carbon.

The five-story, five-sided structure of the Pentagon and everything inside its 6.5 million square feet of office space explodes into superheated dust from the initial flash of light and heat, all the walls shattering with the near-simultaneous arrival of the shock wave, all 27,000 employees perishing instantly.

Not a single thing in the fireball remains.

Nothing.

Ground zero is zeroed.

Traveling at the speed of light, the radiating heat from the fireball ignites everything flammable within its line of sight several miles out in every direction. Curtains, paper, books, wood fences, people’s clothing, dry leaves explode into flames and become kindling for a great firestorm that begins to consume a 100-or-more-square-mile area that, prior to this flash of light, was the beating heart of American governance and home to some 6 million people.

Several hundred feet northwest of the Pentagon, all 639 acres of Arlington National Cemetery—including the 400,000 sets of bones and gravestones honoring the war dead, the 3,800 African American freed people buried in section 27, the living visitors paying respects on this early spring afternoon, the groundskeepers mowing the lawns, the arborists tending to the trees, the tour guides touring, the white-gloved members of the Old Guard keeping watch over the Tomb of the Unknowns—are instantly transformed into combusting and charred human figurines. Into black organic-matter powder that is soot. Those incinerated are spared the unprecedented horror that begins to be inflicted on the 1 to 2 million more gravely injured people not yet dead in this first Bolt out of the Blue nuclear strike.

Across the Potomac River one mile to the northeast, the marble walls and columns of the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials superheat, split, burst apart, and disintegrate. The steel and stone bridges and highways connecting these historic monuments to the surrounding environs heave and collapse. To the south, across Interstate 395, the bright and spacious glass-walled Fashion Centre at Pentagon City, with its abundance of stores filled with high-end clothing brands and household goods, and the surrounding restaurants and offices, along with the adjacent Ritz-Carlton, Pentagon City hotel—they are all obliterated. Ceiling joists, two-by-fours, escalators, chandeliers, rugs, furniture, mannequins, dogs, squirrels, people burst into flames and burn. It is the end of March, 3:36 p.m. local time.

It has been three seconds since the initial blast. There is a baseball game going on two and a half miles due east at Nationals Park. The clothes on a majority of the 35,000 people watching the game catch on fire. Those who don’t quickly burn to death suffer intense third-degree burns. Their bodies get stripped of the outer layer of skin, exposing bloody dermis underneath.

Third-degree burns require immediate specialized care and often limb amputation to prevent death. Here inside Nationals Park there might be a few thousand people who somehow survive initially. They were inside buying food, or using the bathrooms indoors—people who now desperately need a bed at a burn treatment center. But there are only ten specialized burn beds in the entire Washington metropolitan area, at the MedStar Washington Hospital’s Burn Center in central D.C. And because this facility is about five miles northeast of the Pentagon, it no longer functions, if it even exists. At the Johns Hopkins Burn Center, forty-five miles northeast, in Baltimore, there are less than twenty specialized burn beds, but they all are about to become filled. In total there are only around 2,000 specialized burn unit beds in all fifty states at any given time.

Within seconds, thermal radiation from this 1-megaton nuclear bomb attack on the Pentagon has deeply burned the skin on roughly 1 million more people, 90 percent of whom will die. Defense scientists and academics alike have spent decades doing this math. Most won’t make it more than a few steps from where they happen to be standing when the bomb detonates. They become what civil defense experts referred to in the 1950s, when these gruesome calculations first came to be, as “Dead When Found.”

At the Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling, a 1,000-acre military facility across the Potomac to the southeast, there are another 17,000 victims, including almost everyone working at the Defense Intelligence Agency headquarters, the White House Communications Agency headquarters, the U.S. Coast Guard Station Washington, the Marine One helicopter hangar, and scores of other heavily guarded federal facilities that cater to the nation’s security. At the National Defense University, a majority of the 4,000 students attending are dead or dying. With no shortness of tragic irony, this university (funded by the Pentagon and founded on America’s two-hundredth birthday) is where military officers go to learn how to use U.S. military tactics to achieve U.S. national security dominance around the world. This university is not the only military- themed higher-learning institution obliterated in the nuclear first strike. The Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy, the National War College, the Inter-American Defense College, the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, they all immediately cease to exist. This entire waterfront area, from Buzzard Point Park to St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church, from the Navy Yard to the Frederick Douglass Memorial Bridge, is totally destroyed.

Humans created the nuclear weapon in the twentieth century to save the world from evil, and now, in the twenty-first century, the nuclear weapon is about to destroy the world. To burn it all down. The science behind the bomb is profound. Embedded in the thermonuclear flash of light are two pulses of thermal radiation. The first pulse lasts a fraction of a second, after which comes the second pulse, which lasts several seconds and causes human skin to ignite and burn. The light pulses are silent; light has no sound. What follows is a thunderous roar that is blast. The intense heat generated by this nuclear explosion creates a high-pressure wave that moves out from its center point like a tsunami, a giant wall of highly compressed air traveling faster than the speed of sound. It mows people down, hurls others into the air, bursts lungs and eardrums, sucks bodies up and spits them out. “In general, large buildings are destroyed by the change in air pressure, while people and objects such as trees and utility poles are destroyed by the wind,” notes an archivist who compiles these appalling statistics for the Atomic Archive.

As the nuclear fireball grows, this shock front delivers catastrophic destruction, pushing out like a bulldozer and moving three miles farther ahead. The air behind the blast wave accelerates, creating several-hundred-mile-per-hour winds, extraordinary speeds that are difficult to fathom. In 2012, Hurricane Sandy, which did $70 billion in damage and killed some 147 people, had maximum sustained winds of roughly 80 miles per hour. The highest wind speed ever recorded on Earth was 253 miles per hour, at a remote weather station in Australia. This nuclear blast wave in Washington, D.C., destroys all structures in its immediate path, instantly changing the physical shapes of engineered structures including office buildings, apartment complexes, monuments, museums, parking structures—they disintegrate and become dust.

That which is not crushed by blast is torn apart by whipping wind. Buildings collapse, bridges fall, cranes topple over. Objects as small as computers and cement blocks, and as large as 18-wheeler trucks and double-decker tour buses, become airborne like tennis balls.

The nuclear fireball that has been consuming everything in the initial 1.1-mile radius now rises up like a hot-air balloon. Up from the earth it floats, at a rate of 250 to 350 feet per second. Thirty-five seconds pass. The formation of the iconic mushroom cloud begins, its massive cap and stem, made up of incinerated people and civilization’s debris, transmutes from a red, to a brown, to an orange hue. Next comes the deadly reverse suction effect, with objects—cars, people, light poles, street signs, parking meters, steel carrier beams—getting sucked back into the center of the burning inferno and consumed by flame.

Sixty seconds pass.

The mushroom cap and stem, now grayish white, rises up five then ten miles from ground zero. The cap grows too, stretching out ten, twenty, thirty miles across, billowing and blowing farther out. Eventually it reaches beyond the troposphere, higher than commercial flights go, and the region where most of the Earth’s weather phenomena occurs. Radioactive particles spew across everything below as fallout raining back down on the Earth and its people. A nuclear bomb produces “a witch’s brew of radioactive products which are also entrained in the cloud,” the astrophysicist Carl Sagan warned decades ago.

More than a million people are dead or dying and less than two minutes have passed since detonation. Now the inferno begins. This is different from the initial fireball; it is a mega-fire beyond measure. Gas lines explode one after the next, acting like giant blowtorches or flamethrowers, spewing steady streams of fire. Tanks containing flammable materials burst open. Chemical factories explode. Pilot lights on water heaters and furnaces act like torch lighters, setting anything not already burning alight. Collapsed buildings become like giant ovens. People, everywhere, burn alive.

Open gaps in floors and roofs behave like chimneys. Carbon dioxide from the firestorms sinks down and settles into the metro’s subway tunnels, asphyxiating riders in their seats. People seeking shelter in basements and other spaces belowground vomit, convulse, become comatose, and die. Anyone aboveground who was looking directly at the blast—in some cases as far as thirteen miles away—has been blinded.

Seven and a half miles out from ground zero, in a 15-mile diameter ring around the Pentagon (the 5 psi zone), cars and buses crash into one another. Asphalt streets turn to liquid from the intense heat, trapping survivors as if caught in molten lava or quicksand. Hurricane-force winds fuel hundreds of fires into thousands of fires, into millions of them. Ten miles out, hot burning ash and flaming wind-borne debris ignite new fires, and one after another they continue to conflate. All of Washington, D.C., becomes one complex firestorm. A mega-inferno. Soon to become a mesocyclone of fire. Eight, maybe nine minutes pass.

Ten and twelve miles out from ground zero (in the 1 psi zone), survivors shuffle in shock like the almost dead. Unsure of what just happened, desperate to escape. Tens of thousands of people here have ruptured lungs. Crows, sparrows, and pigeons flying overhead catch on fire and drop from the sky as if it is raining birds. There is no electricity. No phone service. No 911.

The localized electromagnetic pulse of the bomb obliterates all radio, internet, and TV. Cars with electric ignition systems in a several-mile ring outside the blast zone cannot restart. Water stations can’t pump water. Saturated with lethal levels of radiation, the entire area is a no-go zone for first responders. Not for days will the rare survivors realize help was never on the way.

Those who somehow manage to escape death by the initial blast, shock wave, and firestorm suddenly realize an insidious truth about nuclear war. That they are entirely on their own. Former FEMA director Craig Fugate tells us their only hope for survival is to figure out how to “self-survive.” That here begins a “fight for food, water, Pedialyte . . .”

How, and why, do U.S. defense scientists know such hideous things, and with exacting precision? How does the U.S. government know so many nuclear effects–related facts, while the general public remains blind? The answer is as grotesque as the questions themselves because, for all these years, since the end of World War II, the U.S. government has been preparing for, and rehearsing plans for, a General Nuclear War. A nuclear World War III that is guaranteed to leave, at minimum, 2 billion dead.

To know this answer more specifically, we go back in time, more than sixty years. To December 1960. To U.S. Strategic Air Command, and a secret meeting that took place there.

Copyright © 2026 by Annie Jacobsen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

© Hilary Jones

Annie Jacobsen is the author of the Pulitzer Prize–finalist in history The Pentagon’s Brain, the New York Times bestsellers Area 51 and Operation Paperclip, and other books. She was a contributing editor at the Los Angeles Times Magazine. A graduate of Princeton University, she lives in Los Angeles with her husband and two sons.