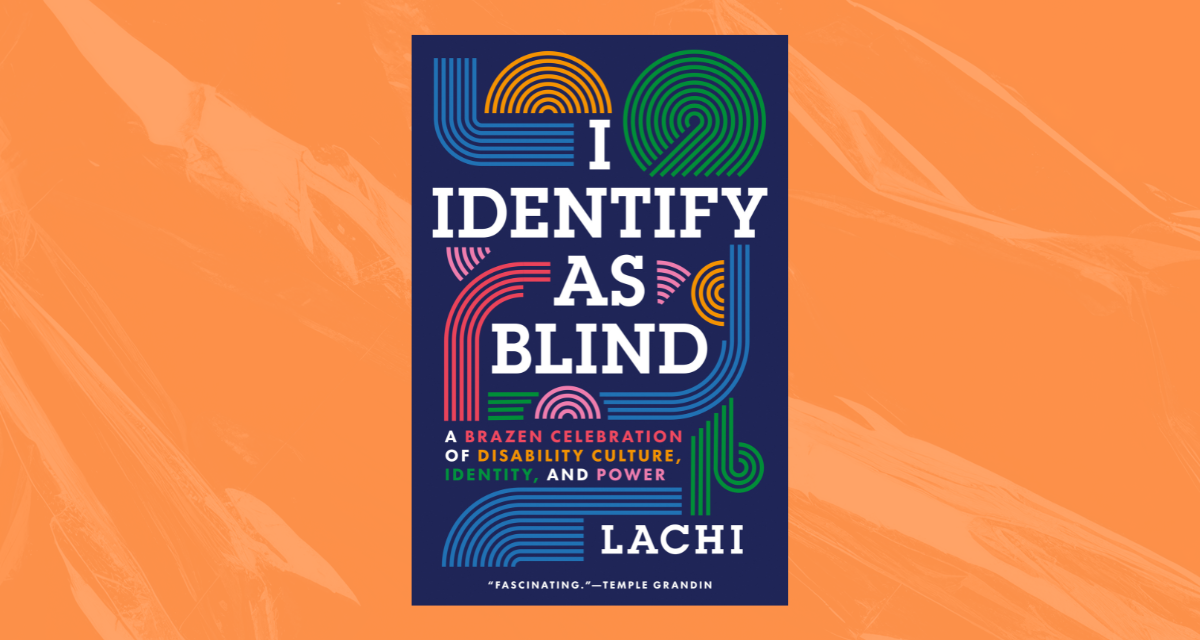

Through magnetic storytelling and pop-culture deep dives, Lachi challenges mainstream views on disability and neurodivergence with humor and heart. Because visionaries with disabilities have always driven progress. The book features trailblazing figures like Senator Tammy Duckworth, Breaking Bad star RJ Mitte, Microsoft executive Jenny Lay-Flurrie, and so many more. Lachi even takes readers behind the scenes at Coldplay concerts, since after Chris Martin developed tinnitus, he transformed his concerts into some of the most accessible in the world. Each story reframes disability not as a deficit but as a wellspring of collective strength.

Chapter 8: Shame on Who Exactly?

I’ve found that the more I “un-normal,” the higher my quality of life. Remember those miracle contact lenses I could wear, but don’t? Here’s the backstory. It was 2018, and I was taking the first baby steps toward accepting my rapidly diminishing vision (even though I wouldn’t fully “come out” until the pandemic). When my ophthalmologist told me about the contacts, of course I said, “Tell me more,” because who wouldn’t? But after doctor visit after doctor visit to get the things custom-fitted, honestly, I just got kinda bored. I would be sitting in the clinic for the third time in a week, thinking, I could be performing, I could be recording, I could be day drinking, I could be doing literally anything but waiting around in a waiting room. Yawn.

Meanwhile, as my contacts were being manufactured, I had finally started using a cane—just the traditional white cane; the rhinestone-bedecked show stoppers were still to come—and becoming more familiar with readily available assistive technologies like magnifiers, dictation, screen readers, and every blind person’s ultimate war hammer, the keyboard shortcut. I was getting everything done that I’d been hoping to do after I got the contacts and was quicker, more efficient and far less frustrated than I’d ever been. So what exactly did I need the contacts for?

Then the contacts arrived. I put them in . . . and I suppose it should have been a YouTube moment where the music swells, a child points and yells, “Mommy, mommy, look! She can see!” Julie Andrews breaks into song as I marvel, teary-eyed, at how clear and beautiful all of my favorite things are now. But there were no heavenly choirs singing or angels weeping. Underwhelming springs to mind. Once I got past the first couple days of piercing headaches, my vision was definitely clearer, but my reaction to the whole experience was very much, “Meh.” It would take up precious time and energy to put the damn things in, take them out, clean them, mentally adjust, and navigate our busted-ass healthcare system to have them refitted as my eyes evolved. Seeing was a hassle. So I took the contacts out and kept it moving.

If you’re like, “Dude, not using those contacts to improve your vision makes zero sense,” then you might also be part of the fifty-two percent of Americans who—according to a Reuters poll—would rather die than live with a disability. (Believe me, we’ll come back to that.) Here’s the deal. I had all the tools I needed to work hard, play hard, rinse, and repeat at pace with any sighted person, which meant I had options. For me, it was not better to have clearer eyesight with all the strings that came attached to it. So I said, “Screw it,” and never looked back.

I’m aware that I had the privilege to say “Screw it.” I had the health insurance to cover, at least in part, the cost of the contacts and doctor visits. I had the money for cabs and Ubers to get to and from the visits on my own. If I lost my sight completely, I had family and friends that would support me. I had Arthur, I had a rainy day fund, but most importantly, I had good credit. Not everyone has those things. I did, so I could afford to say a polite “thank you, next” to something that, for someone else, might have been indispensable.

But that wasn’t the only reason I decided to ditch the contacts. It had taken me years of swallowing tears, wearing fake smiles, and being a brave little toaster to get to a point where I was relatively immune to the entree of shame society tried to serve me whenever I dined at its table. For so long, I’d felt a deep-rooted shame at being legally blind, and that shame informed my decisions and contributed to my anxiety. But as I grew older and more confident, I started to feel pride in my talent, at who I was becoming, what I was capable of, and how I was showing up in the world. But I was still blind. So obviously the blindness was never the problem.

Let’s be real. I hadn’t been considering the contacts so I could see better, but so I could be more acceptable to society—be more “normal.”

So my 2.0-self chose to dump those contacts, to live and give Blind Queen energy, and to lean into all the competitive advantages that come with my Disability identity. My OCD gives me sharp attention to detail, acute communication, and studious punctuality. My ADHD powers hyperfocus and follow-through on my many whimsical ideas, along with abundant energy, spontaneity and the drive to take action. My anxiety fosters excitement, critical thinking, and analytical skills while also bringing empathy, self-awareness, and growth. My PTSD keeps me transparent and considerate of others’ needs. My maladaptive daydreaming—which is what it sounds like, excessive and vivid daydreaming, often to escape internalized stigmas or to cope with anxiety or depression—had involved me conjuring epic sagas for several hours at a time, even to the point of skipping meals, but eventually the ideas coalesced into my sci-fi thriller Death Tango. My blindness grants me creative problem solving, driven focus, a bunch of unique life experiences, self-determination and yes, dope-ass glam canes. When it comes to my built-in life-hacks, I choose pride.

Not everyone does. The flip side of pride is shame, and if you’re looking for the Mother of All Afflictions in the Disability community, shame got game. Let’s you and me break it down.

Macro- and Micro-Shame

Stigmas, barriers, and exclusion don’t happen because of our conditions but because of our conditioning. Every person with any form of disability or neurodivergence has felt the sting of shame. We feel it when the kids in our class pick on or avoid us, and when teachers get exasperated for needing to repeat things because we don’t learn like the other kids. We feel it when Becky in accounting sighs heavily at having to hold the elevator door for a slow-moving cane user. John the wheelchair user (who still just wants to enjoy a beer) isn’t ashamed that he uses a wheelchair; his shame comes from how others exclude or patronize him for being in the chair.

No one experiences shame quite as viscerally as people with disabilities, and it’s the distinct product of ableism. Ableism and shame go together like gin and tonic, Bordeaux and stinky cheese, control-C and control-V. Now, who can refresh our memory on what ableism is? Yes, you in the back of the class. Very good: ableism is prejudice against individuals with disabilities based on the belief that they are inherently inferior to people without those disabilities.

A more thorough working definition comes from lawyer and community organizer TL Lewis. Lewis describes ableism as a means of assigning value to people’s bodies and minds based on the societally constructed standards of beauty, productivity, intelligence, fitness, and what it means to be normal. Lewis also contends that those ideas are rooted in dominance ideologies like eugenics, anti-Blackness, misogyny, colonialism, and capitalism.

I also appreciate writer and organizer Vinay Krishnan’s plain-language definition. In his Medium article, “The Sick and the Well,” he writes, “What ableism comes down to is this—I’m healthier than you are. There’s something inherently wrong with you that is right with me. If there’s a fire. If there’s a flood. If only one of us can make it out alive. It should be me. This isn’t just the thought in the minds of bigoted people—something to be combated with knowledge and experience. This is the ethos of whole systems.”

Ableist biases often show themselves through microaggressions, pocket-sized acts of everyday isms like mansplaining, whitesplaining, and straightsplaining (which is when a straight person drives a chat with a queer person into a ditch by saying something like, “I know exactly what you mean. I have a gay friend who . . . “). Ableism also shows up in the daily indignities that disabled people endure for having the temerity (a good Atticus Finch word) to want to use the bathroom or grab a drink at a bar.

During the lead up to the Great P. Diddy Unraveling of 2024, I, like every red-blooded Black human, was privately popcorn-binging RealLyfe Street Starz, Club Shay Shay, and The Breakfast Club on YouTube for to-the-minute updates like they were a dirty little secret between me and my Android. During this time, I came across the well-meaning yet harmful brand of ableism.

The hip-hop community hasn’t had many prominent anti-ableist voices, so I definitely find it necessary to grant some grace as we grow and find our empathy, language, and humanity. A few incidents stood out to me, but a particularly interesting one transpired on RealLyfe’s video podcast So Let’s Talk About It, Episode 20, with special guest Jaguar Wright, who’s now considered a whistleblower against high-powered hip-hop moguls. At the top of the episode host Angel White introduces herself as “the baddest albino entertainer,” and Jaguar’s smile fades.

“You see yourself as albino?” Jaguar asks with concern in her voice.

“I am,” Angel responds, alongside a few nods from others in the studio.

“You’re light-skinned to me,” Jaguar says. “I don’t understand what you’re talking about.” The room then gets awkwardly quiet as Angel smiles and searches for words. Jaguar continues with, “I love you just the way you are. I hate labels. Just beauty,” ending with a quiet “awww” purr.

Angel begins to say something, then settles on an “I appreciate it,” and quickly moves the conversation along to get the show started.

Let’s break down the well-meaning microaggression. First, Angel demonstrates a healthy dose of identity pride as a woman with albinism. Jaguar’s reaction and statements, though well-intentioned, are harmful. Her question “You see yourself as albino?” displays a negative association not only with the word but with the state of being. Subtext: “Why would you associate yourself with an identity that is self-limiting and shameful?” My identity is my identity; it’s society that ascribes shame to it.

Jaguar’s statement, “I love you just the way you are. No labels,” is giving me “I don’t see color” vibes and hints of traumady. Clearly, Jaguar is a great friend to Angel and meant her no harm as an individual, so Angel doesn’t press the issue and graciously moves things along. A keen viewer would see Angel as the protagonist, a proud woman and gracious host. But there could be many young girls with albinism who watch the episode and think, “Maybe I shouldn’t proudly say I’m a badass woman with albinism because I would be so embarrassed if someone said ‘Aww’ to me under their breath.”

A few friends cautioned me to watch what I say about hip-hop as it pertains to disability. To that I offer these bars: Let ’em break my legs. To try to hold me back. I’m already moving steady in the Dis track! Whether I’m running or I’m rolling, as long as I’m breathing, Ima keep on pushing. Best believe it.

Point blank, period. New paragraph.

These types of microaggressions can also be far less subtle, far less well-intentioned, and can happen at any demographic intersection. Actress Keira Allen, who we heard from several chapters back, has vivid recollections of the micro-shaming she’s experienced since becoming a wheelchair user. When we met in Manhattan, she recalled, “One of those shames the world tries to impose upon disabled people is the subtle messages of, ‘You shouldn’t be outside of the house. The sidewalk isn’t for you. This building isn’t for you.’”

She went on, “Before I go to a restaurant, I always Google its accessibility. I call the restaurant and ask, ‘Are you wheelchair accessible? Are there any steps to get in?’ Even then, there’s only a fifty percent chance that it actually is accessible even if I get all the right answers to those questions. One time I came to this restaurant with two friends who I had known for less than a year, and I was still afraid that these accessibility issues were going to come up and they would say, ‘This is too complicated. She’s not worth it.’”

“We came to this restaurant and there was a step up to get in. I said, ‘Hey, you said you were wheelchair accessible.’ They brought out a tiny little ramp and seemed so put out by having to put it there. I was so worried that I would never see these friends again. I have lost friends like that from them becoming overwhelmed and not wanting to go out with me anymore, which they never admit. They just disappear.”

What Kiera is describing here is social avoidance—losing a friend, a gig, or one’s social standing as a result of ableism or any other form of prejudgment. Another passive micro-shaming signal is spotlighting, singling out a person with a disability under the guise of helping them, which ultimately leaves them feeling uncomfortable and on display. Examples include over-the-top praise, loudly admonishing others for their behavior around a disabled person (i.e. “How dare you not help her!”), or making a Tony-worthy show of your effort when assisting someone with a disability.

“I rarely take the bus because I’ve had so many experiences with bus drivers being angry at me for asking them to put down the ramp,” Kiera concluded. “I have every marker of wealth, privilege, and whiteness, and still I get treated like this. I can’t even imagine what it’s like for people who don’t have all those privileges.”

Ableism cuts across every other societal marker. It doesn’t matter your race, gender, sexual preference, income status, or size. If you’re epileptic, a crutch user, non-speaking, or don’t read as fast as others, you might be shamed because of it. It’s the weight of this societal shame—not the disability—that makes people feel othered, like we’d rather duck and cover than face another eyeroll or patronizing “Aww.”

It’s why many people with non-apparent disabilities do what they can not to disclose, to “pass.” According to Attitude Is Everything, seventy percent of music performers keep their disabilities hidden for fear of damaging a professional relationship. That’s why for years I stumbled over steps, squinted at screens, and missed deal-making waves: I feared disclosure. Since going public about my Disability identity, that fear now seems silly. But hindsight is twenty-twenty. When you live in fear of someone discovering your secret Disability identity, that shame towers over you like Godzilla—the original, not the remake.

Copyright © 2026 by Lachi. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

© Caroline Mariko Stucky | New York, New York

Lachi is an award-winning recording artist, a co-producer of a Grammy-nominated album, a public speaker, and the first openly disabled National Trustee of the Recording Academy. She is the CEO of RAMPD (Recording Artists and Music Professionals with Disabilities), which has partnered with Netflix and Live Nation. Named a USA Today Woman of the Year and a “dedicated foot soldier for disability pride” by Forbes, Lachi hosted the PBS American Masters series Renegades, has appeared on Good Morning America, and she has spoken at The White House. She lives in New York City.