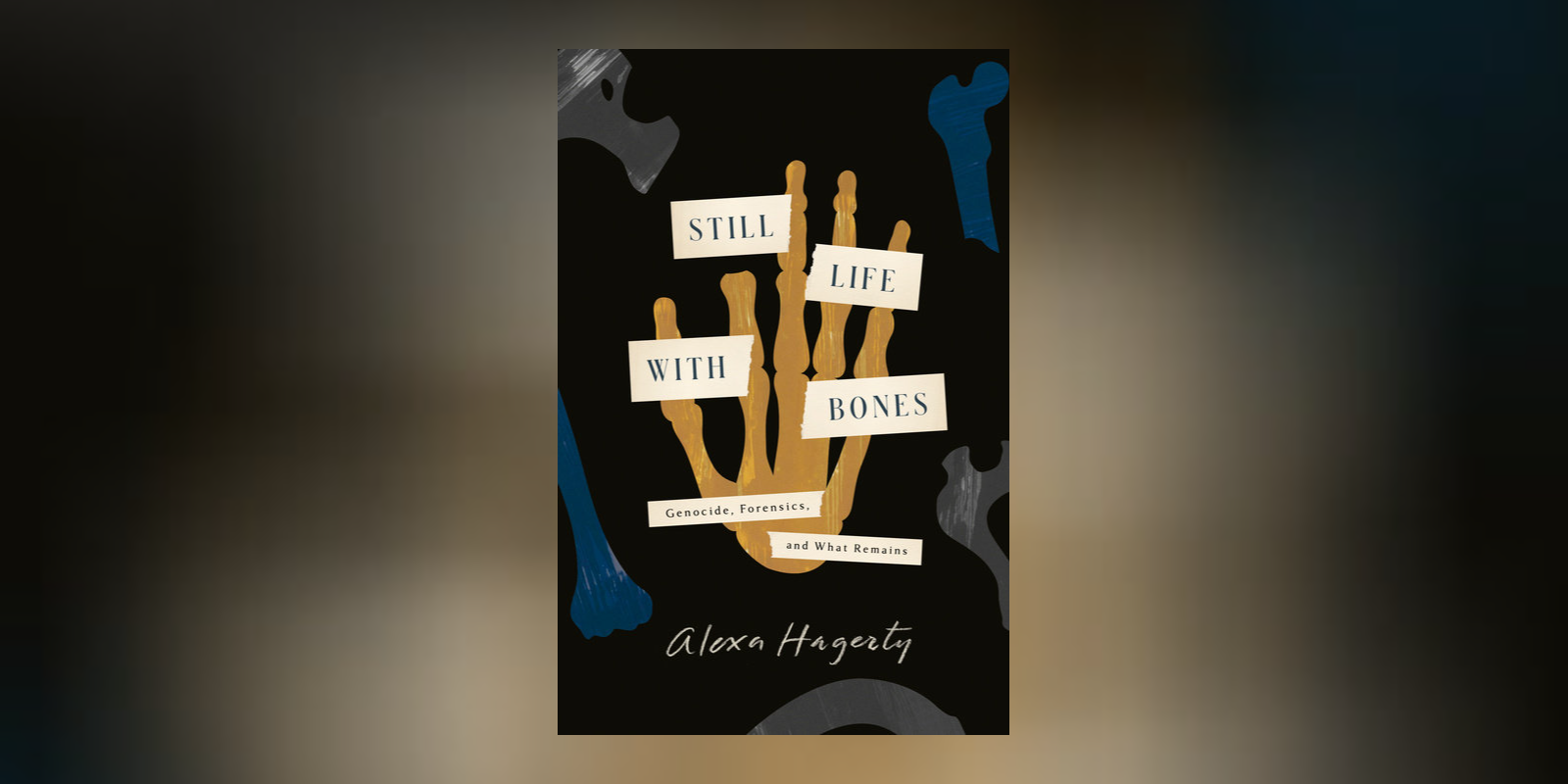

Contributed by Alexa Hagerty, author of Still Life with Bones: Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains. In the wake of genocidal violence, anthropologist Alexa Hagerty works with forensic teams at mass grave sites and in labs, discovering how bones bear witness to crimes against humanity and how exhumation can bring families meaning after unimaginable loss. She also comes to see how cutting-edge science can act as ritual—a way of caring for the dead with symbolic force that can repair societies torn apart by violence.

I knelt in a mass grave in rural Guatemala, carefully brushing dirt from human remains buried decades earlier. As I uncovered the bones of victims of a massacre, I looked up to see community members standing at the edge of the excavation site, watching intently. This wasn’t just a forensic exhumation to prove crimes against humanity—it was a living memorial, a community’s ongoing search for their disappeared, and a powerful reminder that the quest for truth and justice continues long after conflicts officially end.

In my book Still Life with Bones: Genocide, Forensics, and What Remains, I document my experiences as a social anthropologist working alongside forensic teams in Latin America as they recover and identify victims of political violence. Throughout Guatemala’s 36-year armed conflict, state forces killed more than 200,000 people in genocidal violence primarily targeting Indigenous Maya communities. Argentina’s military dictatorship “disappeared” up to 30,000 citizens, including students, educators, and journalists who opposed the regime. In both countries, families of the missing confronted not just personal grief but official denial.

As we witness catastrophic violence in Gaza, Ukraine, and Sudan today, the work of forensic teams has urgent relevance. What happens after the bombing stops? How do communities rebuild when faced with overwhelming loss? When international attention shifts to the next crisis, who remains to undertake the slow, painstaking work of recovery and remembrance?

Forensic exhumation serves multiple purposes simultaneously. In legal terms, it provides evidence for prosecutions and human rights cases, documenting patterns of violence that might otherwise be minimized or suppressed. But equally important are its psychological and social functions. For families, recovering remains allows them to lay their loved ones to rest with dignity. For communities, it creates spaces for collective witnessing and remembrance. And for societies, it establishes factual accounts that counter narratives of denial and erasure. The scientific process becomes a form of care—for the dead, certainly, but equally for those who continue to search for their loved ones.

In conflicts around the world, forensic exhumation is now a standard human rights practice. But it might surprise readers to learn that this approach did not originate in CSI-style laboratories in the Global North. It started with families in Argentina during the transition from dictatorship to democracy in the 1980s. When mothers of the disappeared demanded answers, a small group of university students began to search for victims of the dictatorship’s violence. These young scientists worked at tremendous personal risk, literally digging for evidence of state crimes while being watched by the same authorities who had committed those crimes. What began as a profound act of courage in Argentina became a model replicated worldwide, transforming how societies confront histories of mass violence.

Working alongside teams in Argentina and Guatemala, I learned to see the dead body with a forensic eye. I examined bones for marks of torture and fatal wounds—hands bound by rope, machete cuts—but also for signs of identity: how life shapes us down to the bone. A weaver could be identified from the tiny bones of the toes, molded by kneeling before a loom; a girl found alongside her pet dog. In the tenderness of understanding these bones, forensics offers not just proof of mass atrocity but also tells the story of each individual life lost. While violence seeks to dehumanize, the careful work of recovery restores humanity.

Still Life with Bones maps this journey from erasure to recognition. As students navigate a world of ongoing violent conflicts and as scientific evidence itself faces unprecedented skepticism and denial, I hope these testimonies of families of the missing and forensic teams illuminate how societies can reckon with traumatic histories with integrity. These accounts bear witness to violence but also to humanity’s extraordinary resilience—our capacity to confront difficult truths and weave new possibilities for justice from the aftermath of atrocity.