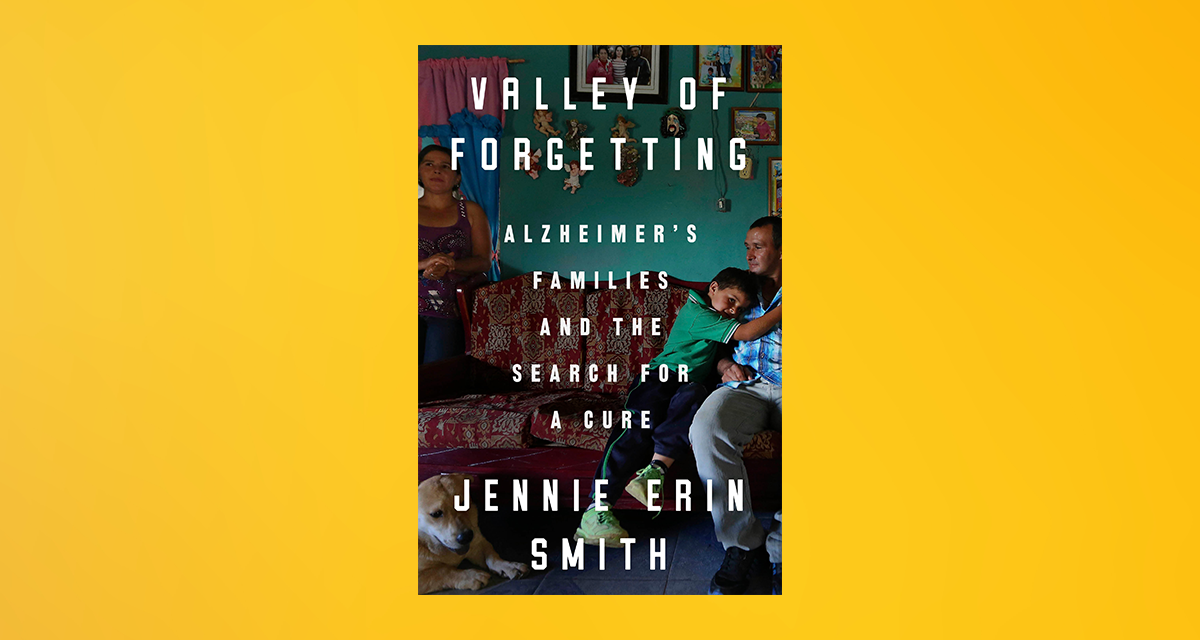

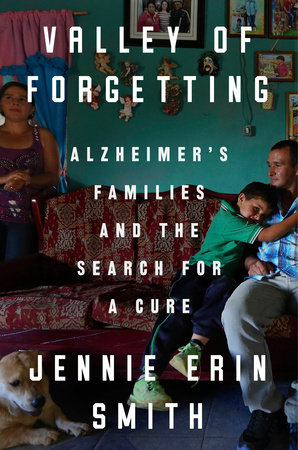

Valley of Forgetting is a very readable and vivid science narrative that offers a rare worm’s eye view of clinical research in Latin America, from the perspectives of both the subjects and the investigators. I spent seven years researching and writing it, most of that time in Medellin, Colombia.

The book tells the story of a 40-year effort, led by the late Colombian neurologist Francisco Lopera, to understand the genetics and natural history of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease in a giant extended family that carries a unique genetic mutation. It relates Dr. Lopera’s efforts to study the 6,000 members of that family despite the dangerous and violent conditions in which they lived. It covers the genesis and execution of a landmark clinical trial in this population. And it delves deeply into the lives of the mostly poor Colombians who have participated in this science for generations.

The book has received extraordinary reviews from, among others, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, and The New Yorker, which wrote that, in this work, “flat questions of the ethics of medical research rendered in rich dimension.”

I agree with this and believe that the book would be illustrative for a course on medical or clinical research ethics. Because it is also a deeply human story, following the protagonists as they navigate a catastrophic illness or the threat of it, students will likely find the reading easy to engage with, even as the book packs in complex and ethical and scientific concepts. It would be valuable to any students of medicine, especially neurology, or neuropsychology. People studying nursing, healthcare policy or health equity would also find it provocative, as would caregivers.

One of Valley of Forgetting’s central dramas is a clinical trial of an Alzheimer’s drug that enrolled hundreds of people, most of them poor. At baseline all of them were still healthy, and the trial was to see if the drug could keep them from developing dementia. For eight years the participants lived with onerous restrictions on their lifestyle choices, and had to undergo invasive testing, including spinal taps and PET scans.

But there was something unusual about this cohort: not all participants carried the mutation. They would never have gotten sick. For nearly 40 years under Dr. Lopera, they weren’t given the option to know whether they carried the mutation or not. Whether this policy was justified, and how and when to change it, presents an ongoing dilemma in this book.

The study subjects were unpaid, but for minor reimbursements, because conventional wisdom states that vulnerable people should not be tempted to join a drug trial. But the Colombian researchers, and their overseas colleagues, were paid very handsomely for their work. So the book looks in depth at what is fairly owed to participants in clinical research, especially when that research is conducted in developing countries.

It also reveals some of the misunderstandings that can emerge between the investigators and their subjects. What if research is the only type of medical care your family has access to? If you are studying people while you care for them, are your decisions likely to benefit them, or your research?

And finally, who has the right to data from a country like Colombia? Dr. Lopera’s subjects donated their blood, and their relatives’ brains, to his research for 40 years. If a drug is made from those findings, as the investigators hope, what benefit should they see?

This is just a small sample of many lively discussions this book could generate in a class. Students will find that there are few easy answers because, as the book shows all too well, research is complicated and life is complicated, perhaps nowhere more than a place like Colombia.

Jennie Erin Smith is the author of Stolen World. She is a regular contributor to The New York Times and has written for The Wall Street Journal, The Times Literary Supplement, The New Yorker, and others. She is a recipient of the Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award; the Waldo Proffitt Award for Excellence in Environmental Journalism in Florida; and two first-place awards from the Society for Features Journalism. She lives in Florida and Colombia.