How do we understand ourselves when the story about who we are supposed to be is stronger than our sense of self? What do we stand to gain—and lose—by taking control of our narrative?

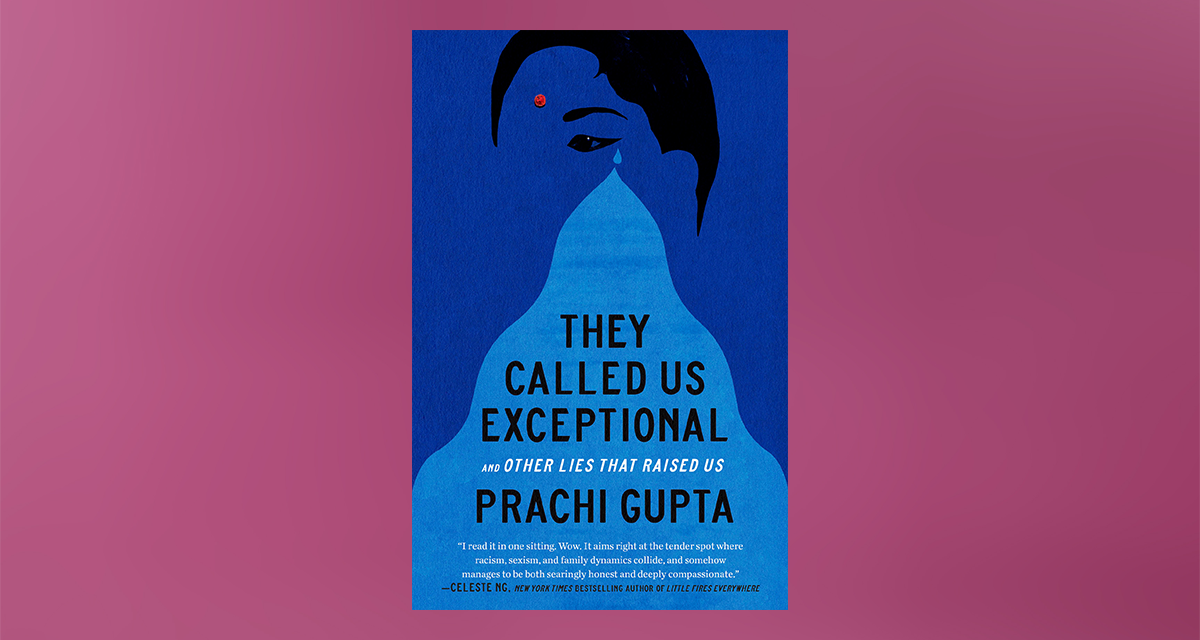

Family defined the cultural identity of Prachi and her brother, Yush, connecting them to a larger Indian American community amid white suburbia. But their belonging was predicated on a powerful myth: the idea that Asian Americans, and Indian Americans in particular, have perfected the alchemy of middle-class life, raising tight-knit, high-achieving families that are immune to hardship. Molding oneself to fit this image often comes at a steep, but hidden, cost. In They Called Us Exceptional, Gupta articulates the dissonance, shame, and isolation of being upheld as an American success story while privately navigating traumas the world says do not exist.

“I read it in one sitting. Wow. It aims right at the tender spot where racism, sexism, and family dynamics collide, and somehow manages to be both searingly honest and deeply compassionate.”

—Celeste Ng, author of Little Fires Everywhere

Chapter 1

Dawn

Kanika has several meanings in Sanskrit, but Papa liked “gold”—an object so striking that people traded it for food and clothing. You preferred the name Prachi. East. Sunrise. Dawn. A nod to the homeland you’d left five years before my birth. A word that, in poetry and literature, represents new beginnings. Papa suggested a creative compromise: Let me decide. If born during daylight, I was to be Prachi. If born at night, I would be Kanika.

I was born just as the sun began its climb into the sky, exercising its full power on a hot day in the middle of July. I had made my choice clear.

I wish I had asked you why you picked the name Prachi. Instead, I remember telling you when I began to hate my name. Jessica and the other white girls in my pre-kindergarten class played a game: One girl had candy in her hands, and she would open and shut her palms quickly. The girl next to her had to pick pieces of candy from her friend’s hands before she clamped them shut. I asked Jessica if I could play. She smiled and said, “Give me your hand.” Then Jessica grabbed my fingers and yanked them back toward my wrist and looked into my eyes as I yelped in pain. She laughed. The teachers ignored me when I told them that Jessica had hurt me.

I didn’t tell you what had happened. Instead, when I came home, the confusing, turbulent feelings inside me distilled to one question: “Why didn’t you name me Jessica?” I think you were taken aback, and in your surprise, you apologized. I didn’t have the words for racism yet. I only understood that if I was more like Jessica somehow, I wouldn’t have been treated that way. “I’m sorry,” you said, accepting my feelings as fact, likely unaware of the cruelty children inflict on those who look unlike them. “I liked Prachi.”

I wish I could tell you now that I love my name.

We had moved to the Land of Jessicas in New Jersey from Silicon Valley, where we’d lived among one of the biggest Indian communities in the country. In California, Papa owned a townhouse and began a lucrative career as a hardware and software engineer, a rare skill set that positioned him well for the coming tech boom. After your initial years surviving icy Canadian winters, you welcomed the warmth. You looked after me at home, and eighteen months later, to the day, Yush arrived. For most of my childhood, I thought that half birthdays were the day that one’s sibling was born.

At first, I envied the attention you gave Yush. You told me that once, while you were changing his diaper in the bathroom, you left him alone for just a moment. I snuck in and locked the door behind me. Like a hostage negotiator, you cajoled and convinced me to open the door. Yush remained unaware of the danger he was in. He was the easy baby: He sat with anyone, content in his own world. He was like you—gentle, mild-mannered, and kind. I was the fussy, possessive, mischievous one, clawing at you for constant attention. My temperament mirrored Papa’s—stubborn, opinionated, strong-willed, outspoken, and loud. Traits admired and encouraged in my father but concerning when manifested by a girl. Yet Papa was proud of me. I, in turn, thought that Papa looked the way all papas should: thick curly hair with a nascent bald spot, a strong black mustache, and a slight paunch.

Just as your amorphous future in America acquired a shape, Papa abandoned his promising engineering career and propelled us into the unknown. His decision to pursue medicine came top-down, like a CEO’s directive. Dadaji tried to talk Papa out of this doctor business. “Think of what this means for your wife and little kids,” Dadaji said. To him, it sounded like another one of his son’s impulsive decisions. Papa was angry that his father, who had always felt distant, yet again withheld his emotional support.

Papa said that he made a long list of reasons why it made sense for him to switch careers, as if it were a purely logical decision. But this was not a simple job change; this was accumulating a mountain of debt and earning little income and relocating the family every few years to complete medical school, residency, fellowship, and specialized surgical training. It was a decision that meant you’d have to raise two young kids in an unfamiliar country with little support as your husband worked long hours. It was a decision that meant you would move too often to build a close circle of friends. You would see your parents only a handful of times again in your life because we could not afford frequent trips to India. When your parents died, we would meet your grief like strangers.

Papa was passionate about medicine and wanted to help people. But somewhere on Papa’s list of reasons—the one that stands out to me now above all of the others—is this: He noted that being a doctor would earn him more respect, particularly within the Indian community. I had underestimated the power and the depth of that desire and how the force of that current swept up the rest of us.

Papa moved to New Jersey for medical school and lived in student housing. He worried that we would distract him from his studies, so he sent the three of us to live with Dadiji and Dadaji in Toronto, where he expected us to stay for the next four years. I remember the extended visit at their apartment building only in flashes: Yush and I running around a 200-meter indoor track on the top floor; entering the narrow mail room with anticipation for packages from Papa; opening a box to find the T-shirts he sent us—a peach shirt with a beach sunset cartoon graphic for me, a tiny blue shirt for Yush. I think it was during that first year that I grabbed ahold of crayons and drew all over the white walls, and then Dadiji and Dadaji had to repaint them, after which I did it again: untamed signs of what would become a lifelong passion for painting and drawing.

I was Dadiji’s little Pachu, Yush her Yushie Bushie. Through her broken English, I was never sure how much she understood of what I said, but it didn’t matter. She expressed her love by squeezing me so hard with her plump body that for a moment I had to hold my breath. Then she smushed her face into mine, shaking her head so vigorously that her prickly mustache hair scratched my skin and reddened my cheeks, and I closed my eyes to shield them, squealing throughout. Dadiji’s apartment housed her entire world: her plants, her original artwork, and photos of family. In the photo that best captures our friendship, Yush and I posed in front of her cascading plants. I am holding him tight, smiling at the camera and squeezing my little brother like he’s my doll. He stands warm and protected as he gazes off into the distance.

Dadiji doted on us, but it was Dadaji who animated me. We exchanged love through banter. His voice was thick and knotty, like a banyan tree, later lilted by a slight slur from a stroke. He spoke in concise, pithy sentences and half sentences, weaving between the sardonic and the serious so quickly that either he or I was always on the verge of laughter. The constant pain from sciatica made him stiff, so he hugged not with his arms but with his hands, showing me how much he missed me with each light, excited pitter-patter on my back. Seeing as I was Prachi, the Goddess of the Rising Sun and Destroyer of Darkness, on gray days he’d say, “Prachi, where is the sun? Call the sun!”

“I tried, but the sun didn’t answer me!” I’d say.

He’d laugh. “Yes, the darkness is not done yet.”

As Papa told it, on his first visit to Toronto that year, I ran to the door and gave him a big hug. As the visit ended, I begged him not to leave. When he left, I cried. When he returned, I was again excited to see him. But as the ritual of Papa’s arrival and departure happened again and again, I stopped coming to the phone to take his calls. Then I refused to meet him at the doorway altogether. “When I came back,” he said, “you wouldn’t even talk to me.”

“Why should I?” I apparently said to him on his last visit. “You’re just going to leave us again,” and I walked off.

He always laughed when retelling that part. “That’s when I said, ‘Uh-oh, I have to watch out. This girl knows what she wants!’ ” Papa said that my protest convinced him to move the family to New Jersey, where he completed the next three years of medical school with us in tow.

Please remember: There was a time when my outspokenness brought us together instead of tearing us apart. There was a time when speaking my mind was received not as a threat but as an act of love.

Copyright © 2023 by Prachi Gupta. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Prachi Gupta is an award-winning journalist and former senior reporter at Jezebel. She won a Writers Guild Award for her investigative essay “Stories About My Brother,” and her work was featured in the Best American Magazine Writing of 2021. She has written for The Atlantic, The Washington Post Magazine, Marie Claire, Salon, Elle, and elsewhere. She lives in New York City.

Prachi Gupta is an award-winning journalist and former senior reporter at Jezebel. She won a Writers Guild Award for her investigative essay “Stories About My Brother,” and her work was featured in the Best American Magazine Writing of 2021. She has written for The Atlantic, The Washington Post Magazine, Marie Claire, Salon, Elle, and elsewhere. She lives in New York City.