Profiles in Mental Health Courage portrays the dramatic journeys of a diverse group of Americans who have struggled with their mental health. This book offers deeply compelling stories about the bravery and resilience of those living with a variety of mental illnesses and addictions.

Several years ago, Patrick J. Kennedy shared the story of his personal and family challenges with mental illness and addiction—and the nation’s—in his bestselling memoir, A Common Struggle. Now, he and his Common Struggle coauthor, award-winning healthcare journalist Stephen Fried, have crafted this powerful new book sharing the untold stories of others—a special group who agreed to talk about their illnesses, treatments, and struggles for the first time.

Chapter One

Philomena

Philomena Kebec is a crusading tribal rights, human rights, and public health attorney for the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians. The forty-five-year-old lawyer lives in a small town just outside the reservation on the northern tip of Wisconsin with her daughter, her son, and her son’s father. But she grew up in a bigger city in nearby Minneapolis, Minnesota-and her advocacy and fierce legal acumen are internationally known.

She has done everything from arguing as a staff attorney at the Indian Law Resource Center in Washington for the UN declaration of rights for all Indigenous peoples in the world to creating an innovative, hyperlocal, all-volunteer harm reduction and needle exchange program serving tribal and nontribal communities in northern Wisconsin.

One podcaster nicknamed her “the bad-ass woman from Bad River.”

I was introduced to Philomena by my friend Michael Botticelli, the former director of National Drug Control Policy for the Obama administration and an addiction medicine expert who is in long-term recovery himself. He told me I should meet her, but he didn’t want to say why.

Within minutes of talking to her, we had moved past her work, and she started discussing what had really been going on in her life. I immediately recognized that while she had been keeping a lot of her experiences to herself in her professional life, she was actually quite accustomed to talking about them-but primarily in the safety of twelve-step recovery meetings. People who share in meetings quickly connect to one another, regardless of the differences in age or circumstance.

I have always gone to tiny, private twelve-step meetings, first in D.C., with fellow public officials who couldn’t be open enough about their addictions to risk being seen by the larger recovery public at a meeting.

(Throughout the book I’m using “twelve-step” to refer to all types of regular peer support meetings for addictions. These originated in the 1930s when “Bill W.” wrote out the twelve steps and created Alcoholics Anonymous, later followed by Narcotics Anonymous and groups for loved ones. There are now many twelve-step groups not affiliated with AA or NA, or strictly following their traditional insistence on secrecy and discouragement of psychiatric and addiction medications. So I’m using the general term.)

Philomena told me she had been in recovery since the age of seventeen, when she stopped binge drinking and smoking pot to such extremes that she once even stole her grandmother’s sacred ceremonial pipe and used it to get high. But after college, when she was working in a bookstore and trying to figure out what to do with her life, she started attending a very large, long-standing meeting in Minneapolis called the Central Pacific. On Thursdays, that meeting would often attract three hundred people and be recorded. So sharing there was a uniquely private yet very public experience.

That big Central Pacific meeting changed Philomena’s life in many ways beyond just helping her maintain her sobriety. It was through the meeting that she met the lawyer who hired her as a paralegal, then helped her get into law school and mentored her as an attorney.

She also refined her advocacy voice at the podium of the Thursday Central Pacific meeting. And nobody who was there that night ever forgot the story she told about the very last time she was abused by her stepfather at the age of twelve-a sharing that I heard about from someone else who was there.

She spoke for more than a half hour with searing, contagious passion, somehow managing to keep to the house rule of “no profanity from the podium.” And then she tried to sum up by describing how she made sense of her feelings about her abuser.

“I’ve prayed a lot,” she said, “and I’ve talked in recovery a lot about how to respond to that . . . to that . . .”

She stopped, total silence, mouth to the microphone, looking out at the audience into people’s eyes, for more than a minute. It took forever.

And then she said, “To that . . . motherfucker!”

The whole room just exploded. “Yes,” people were yelling, “yes!”

But having that kind of effect on people can come at a price. And while Philomena has been solid in her recovery for over twenty-five years, those closest to her know that the rest of her mental health has continued to be challenging. Part of the reason she’s such an effective legal advocate may be that her emotions are so close to the surface; on controversial issues, she doesn’t let go when others might, because she can’t let go.

“Even today,” she told me, “I go through periods where I get really emotionally spun out, really overwhelmed, and I can’t stop crying. I would get cycles of obsessive thoughts, just creating this emotional whirlwind. At this time last year, I was suicidal. I was struggling with a diagnosis of major depression and PTSD. But a lot of that was brought on by workplace stress, too.

“Sometimes the only really effective way of getting out of one of these tailspins has been to engage in suicidal ideation or to cut myself-as I have since I was a teenager. It just ends up taking the wind out of it. And I think what happens, and I’ve talked to my therapist about this, is when I’m planning my death, my frontal lobe gets engaged in something else, and I’m able to get some relief from the emotional turmoil that’s happening in other parts of my brain. I believe this is connected to my PTSD. And it’s really terrifying. The whole thing is really terrifying.”

Because of the nature of her work doing human rights law, she can actually view what is happening to her through different prisms, different worldviews for approaching trauma, mental illness, and addiction.

She learned early on about the traditional twelve-step prism, which would view the main way to address her challenges as simply abstaining from substance use and working the steps. She also came to understand there was a more psychiatric model of treating symptoms and illnesses with talk therapy, which she likes, and medication, which she would prefer not to take but has. Later in her career as a local advocate for health care during the opiate crisis, she got interested in the controversial model of harm reduction and needle exchange-creating safe places for addicts to use opiates, with naloxone (Narcan) on hand to reverse overdoses, and offering sterile injection equipment to lessen the chance of infection. (The harm reduction world is also more open to people taking medication to get off drugs or replace drugs.) And then there’s the more recent idea of using “brain differences” or “neurodivergence” to recast mental illnesses and substance use disorders so they are seen not as diseases or medical conditions but as part of a spectrum of brain functionality.

These different worldviews are crucially important in fighting for human rights-disability rights, health insurance rights, LGBTQ+ rights, tribal rights. But appreciating them all can make the process of understanding what’s wrong with you, and how it should be treated, fairly confusing. Especially when you add the pressures of the outside world to the pressures of your interior world.

“Here’s how I see myself,” she told me. “I’m an attorney who has been practicing for fifteen years. And I’m a person that has struggled with mental illness-and I still struggle with mental illness. Or, while I don’t like that dichotomy, I do have mental differences.”

She also brings the unique perspectives of tribal culture and medicine to the equation. It is not uncommon for people with mental health problems to wish for a more “natural” or “spiritual” way to address them. But they don’t always know how to accomplish that: sometimes those who offer alternative help don’t “believe” in traditional Western mental health medicine and expect people to choose between options that are, honestly, best used together. Psychiatric care and prayer, for example, are a great match: prayer instead of psychiatric care can be dangerous, even deadly.

Philomena was brought up in both Western and tribal cultures. At the moment, her treatment is being overseen by a psychiatric nurse practitioner on the reservation. These specially trained nurse practitioners (NPs)-also called psychiatric-mental health nurse practitioners-are licensed to write prescriptions (primarily for mental health care). But her nurse practitioner also expects that Philomena will seek out traditional Native ceremonies and treatments. These can include prayers, herbal medicines (swallowed, smoked, or smudged), sweat lodge sessions, or ceremonially “putting down tobacco” at the base of a tree-which is done when asking for assistance or permission.

“When I’m having a hard time, I’ll go out and put some tobacco down and ask for pity,” she explained. “I ask for love. I ask for direction.”

Yet her nurse practitioner also expects that if Philomena needs talk therapy, she will get it. And if she needs a prescription medicine for her sleep disorders and her depression, she will take it.

“Mental illness can be a spiritual sickness,” Philomena said, “but there are also Native words for sadness and depression.”

Growing up, Philomena, an only child, lived a fairly assimilated life with her mother; they moved from Chicago to Minneapolis when Philomena was three and her parents divorced. Her father was a prominent Chicago attorney who struggled with bipolar disorder and, later, kidney disease from longtime use of lithium. Her mother was a corporate communications specialist at Xcel Energy who struggled with alcohol use and later became a regular at Minneapolis area AA meetings. Philomena was close to her maternal grandmother, a teacher, and spent childhood summers with her at her home near the reservation, which was three hours away in northern Wisconsin, along Lake Superior.

She recalled her sexual abuse beginning at age eight or nine, when her stepfather, who took care of her in the afternoons because her mom was working full-time and also getting her MBA, created a new rule: she had to take a bath every day after school. When she tried to resist this, he hit her. “Much later,” she told me, “I realized these beatings were to put the fear of God in me, to keep me from speaking about the abuse. I knew, at that young age, that he had a deadly level of rage. That he could lose it and kill me.”

She recalled her mother initially being “oblivious” to what was happening, “buying into all of his stories and justifications” for hitting her, but she finally drew the line when “he lost his shit on me and beat me in front of the next-door neighbors.” Since he blamed his behavior on drinking, the couple went into family outpatient treatment; Philomena, age eleven, and her mother participating as co-dependents in Al-Anon and Alateen. Not long after, her mother decided to join a twelve-step group for her own sobriety.

The situation finally came to a head during a family vacation in the Southwest. One night, her stepfather “started patting me on my chest,” she remembered. “I was wearing one of my favorite T-shirts, from a Janet Jackson concert. I was irritated about that. We were supposed to go somewhere the next morning, and I didn’t want to get up. When I finally did, he smacked the shit out of me-you know with certain people there’s that emotional tornado that just happens very quickly. Once before, he had thrown me against a tile wall in the bathroom and I slammed into the bathtub and lost consciousness. This time I became enraged and empowered; I yelled at him, and I went and told my mom that he had been molesting me. And then we just went on with our day like nothing had happened. We visited Carlsbad Caverns.”

They then drove back to Minnesota, and when they arrived her mother immediately called the police and got a restraining order. “I had to do the sexual assault interview, you know, demonstrate on a doll, all of that,” Philomena recalled. “It was my first interaction with the criminal legal field.” Because she didn’t want to testify in court, her stepfather was able to plead to child assault and not a sexual charge. She had “a tremendous amount of guilt about that,” which stayed with her for a long time. And she has struggled with PTSD and back pain from the assaults.

After the restraining order, Philomena began to see a psychologist. “I remember our first visits,” she said. “I would just go there and go to sleep. I slept a lot in middle school, because I couldn’t sleep when my stepfather was there. He would come into my room and I was scared. So, I had hypervigilance suicidality.”

Self-harm became “a way of life, beginning around age twelve,” she said. “I like to cut, you know. At one point I took a whole bunch of Tylenol and passed out-actually, I never told anybody about that. By sixteen, I was doing a lot of drugs, and I liked to drink vodka, straight, until I couldn’t taste it. In order to survive, I had to compartmentalize. So, there were parts of me that had to be completely walled off. And they were very self-destructive parts of myself. And then, they did not always want to be walled off and kept apart. So, they would kind of barge in, and then ruin things in my life. It sounds really weird and crazy, right?”

I assured her it didn’t sound weird or crazy at all. It sounded familiar.

“I had parents who were very dysfunctional,” she said. “And I had to be an adult, very young. And so I had to become extremely resourceful in getting all of my needs met. And when my mental illness got to a point where I needed to get help, I would query the people around me and find the resources that I needed. I think part of that is a function of having an alcoholic parent, and then part of it is just living in America, right? That’s how we have to function as people. We’re only able to survive insofar as we can muster up the resources to get to the next level of care, right?”

At the height of Philomena’s alcohol and marijuana use, her mother discovered that she had stolen her grandmother’s ceremonial pipe and was using it to get high. Her family was terribly upset, but that did not stop her substance use. Finally, when she was a junior in high school, her mother insisted she go for residential care for alcohol. “My mom was just tired of it,” she recalled. “Because she saw me as somebody who had a lot of potential, she got to a point where she was just going to throw me out. So, at seventeen, it was either go to treatment or be homeless.” She spent forty-five days in a residential program in Blaine, north of Minneapolis-beginning on April 1, 1995, still her sobriety date (or in twelve-step parlance, her “birthday”)-and then three months in a halfway house before returning home for her senior year of high school while attending twelve-step meetings.

Copyright © 2024 by Patrick J. Kennedy. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The Honorable Patrick J. Kennedy is a former member of the U.S. House of Representatives and the nation’s leading political voice on mental illness, addiction, and other brain diseases. During his 16-year career representing Rhode Island in Congress, he fought a national battle to end medical and societal discrimination against these illnesses, highlighted by his lead sponsorship of the Mental Health Parity and Addictions Equity Act of 2008—and his brave openness about his own health challenges. The son of Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy, he decided to leave Congress not long after his father’s death to devote his career to advocacy for brain diseases and to create a new, healthier life and start a family. He has since founded the Kennedy Forum, which unites the community of mental health, and co-founded One Mind for Research. He lives in New Jersey with his wife, Amy, and their four children.

The Honorable Patrick J. Kennedy is a former member of the U.S. House of Representatives and the nation’s leading political voice on mental illness, addiction, and other brain diseases. During his 16-year career representing Rhode Island in Congress, he fought a national battle to end medical and societal discrimination against these illnesses, highlighted by his lead sponsorship of the Mental Health Parity and Addictions Equity Act of 2008—and his brave openness about his own health challenges. The son of Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy, he decided to leave Congress not long after his father’s death to devote his career to advocacy for brain diseases and to create a new, healthier life and start a family. He has since founded the Kennedy Forum, which unites the community of mental health, and co-founded One Mind for Research. He lives in New Jersey with his wife, Amy, and their four children.

www.patrickjkennedy.net

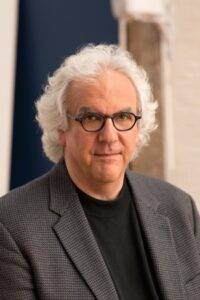

Stephen Fried is an award-winning journalist and New York Times bestselling author who teaches at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and the University of Pennsylvania. He is, most recently, the author of the historical biography Appetite for America, and the coauthor, with Congressman Patrick Kennedy, of A Common Struggle. His earlier books include the biography Thing of Beauty: The Tragedy of Supermodel Gia and the investigative books Bitter Pills and The New Rabbi. A two-time winner of the National Magazine Award, Fried has written frequently for Vanity Fair, GQ, The Washington Post Magazine, Rolling Stone, Glamour, and Philadelphia Magazine. He lives in Philadelphia with his wife, author Diane Ayres.

Stephen Fried is an award-winning journalist and New York Times bestselling author who teaches at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and the University of Pennsylvania. He is, most recently, the author of the historical biography Appetite for America, and the coauthor, with Congressman Patrick Kennedy, of A Common Struggle. His earlier books include the biography Thing of Beauty: The Tragedy of Supermodel Gia and the investigative books Bitter Pills and The New Rabbi. A two-time winner of the National Magazine Award, Fried has written frequently for Vanity Fair, GQ, The Washington Post Magazine, Rolling Stone, Glamour, and Philadelphia Magazine. He lives in Philadelphia with his wife, author Diane Ayres.