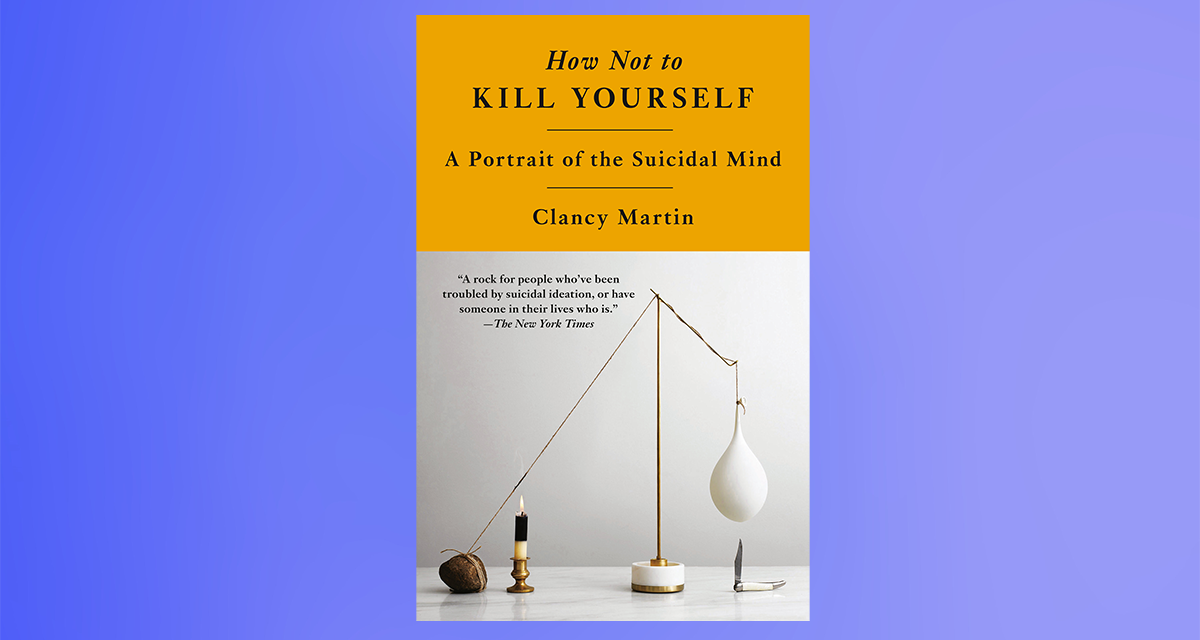

FINALIST FOR THE KIRKUS PRIZE FOR NONFICTION

ONE OF TIME’S 100 MUST-READ BOOKS OF THE YEAR

ONE OF THE NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW’S CRITICS’ PICKS

ONE OF THE BOSTON GLOBE’S 55 BOOKS WE LOVED THIS YEAR

ONE OF KIRKUS’S BEST NONFICTION BOOKS OF THE YEAR

How Not to Kill Yourself is an intimate, insightful, at times even humorous blend of memoir and philosophy that examines why the thought of death is so compulsive for some while demonstrating that there’s always another solution—from the acclaimed writer and philosophy professor, based on his viral essay, “I’m Still Here.”

1. The Suicidal Mind

“You know what’s funny? Your jail anklet saved your life. They should put that in an advertisement. They should get a testimonial from you. If it weren’t for that anklet, you’d be dead right now.”

I came to in a hospital bed with a sore head. I reached into my hair and felt the staples in my scalp. A handsome young darkhaired doctor with a bushy moustache and brightly lit, amused eyes was standing at the side of my bed conversing cheerfully with me. I didn’t know how long he’d been talking or if I had been talking back. I seemed to be joining the conversation midstream. But that might have been his manner: perhaps he simply launched into conversation with his patients and let them catch up when they were ready. I was very thirsty, and still nervously fingering those metal staples, I reached with my free hand for the large plastic cup of water on the bedside table. Then I realized that I was handcuffed to the bed.

“Here, let me get it for you.” He tucked the bottle between the bed rail and the pillow and bent the plastic straw into my mouth. I drank the water and then spat out the straw. My throat was burning.

“Did I have an operation?” I asked.

“No, you were very lucky. Two minor procedures.” He reached over to gesture at my head, where my staples and my fingers were. “You must have fallen at some point. Your head was bleeding. Quite a nasty cut. You have a mild concussion. You’ll probably be experiencing some dizziness and nausea.”

This was my second concussion in less than a year. Seven months before, I’d fallen down some stairs while drunk and had staples on the other side of my head. I couldn’t remember either accident. I remembered taking all the Valium and getting the knife, climbing into the clawfoot bathtub, and keeping my leg hanging out, bent at the knee. I remembered having trouble juggling a glass of wine, the knife, and my phone. I remembered being at Davey’s Uptown Rambler’s Club before coming home and resolving to kill myself that night. But I didn’t remember how I got back from the bar.

“My throat hurts more than my head. My voice,” I said. “I sound awful. I don’t feel sick.”

“We had to pump your stomach, but basically you’re fine. I’m sorry we have to shackle you. They will transfer you to the psychiatric ward tomorrow, and then this security won’t be necessary. You ruined your fancy anklet.” He laughed. He was a very likable doctor. “It seems to have short-circuited. But not before it sent to its alarm. Modern technology.”

I wanted to explain about the anklet, that it wasn’t a court-ordered thing, it was something I was trying on my own to keep myself sober, but I realized that any extra details from me would sound defensive and anyway were superfluous.

Some years later a good friend, a famous scholar of ancient languages, would tell me, “You know lots of people think that a suicide attempt is just a cry for help. A way to get attention. I know that’s not true, because when I woke up in the hospital and realized I was still alive, I was gutted.” That was how I felt: depressed, very disappointed and even more disgusted with myself. Not sad that I’d tried suicide again but miserable that I’d once again failed.

“Next time, don’t get in the bath. Better yet, don’t have a next time, would you? We’d like to keep you around. And if you want to kill yourself, don’t use pills. Nobody dies from overdosing on pills anymore.” Bizarrely, he discoursed for a minute or two on how best to kill oneself. “There’s even a book you can buy that tells you how.”

I knew the book he meant. It’s called Final Exit. I don’t recommend it.

“But you know, you were very lucky, and most people wise up after one attempt. So maybe this can be your get-out-of-jail-free card. That’s how I’d approach it. You take care. Try to behave yourself. Things will get better.”

He grabbed my foot, shook it gently, even affectionately, shrugged, and left the room.

I thought, Well, that was actually kind of nice. It was a much more pleasant encounter than you’d expect with a doctor after you’d attempted suicide. That guy ought to be training others on how to deal with people in my situation.

I had an IV in my arm. There was a phone by the bed, but I couldn’t reach it, because it was on the handcuffed side. I had a nurse alert button by my hand, but I didn’t want to beep a nurse to help me make a phone call.

“Three weeks ago I was in bed at home with my girlfriend,” I said out loud, theatrically, to the empty hospital room. “Three weeks ago everything was normal.”

But that wasn’t the truth. My life had been abnormal for a long time.

Copyright © 2023 by Clancy Martin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

© Lauren Schrader

CLANCY MARTIN is the acclaimed author of the novel How to Sell (FSG) as well as numerous books on philosophy. A Guggenheim Fellow, his writing has appeared in The New Yorker, New York, The Atlantic, Harper’s, Esquire, The New Republic, Lapham’s Quarterly, The Believer, and The Paris Review. He is a professor of philosophy at the University of Missouri in Kansas City and Ashoka University in New Delhi. He is the survivor of more than ten suicide attempts and a recovering alcoholic.