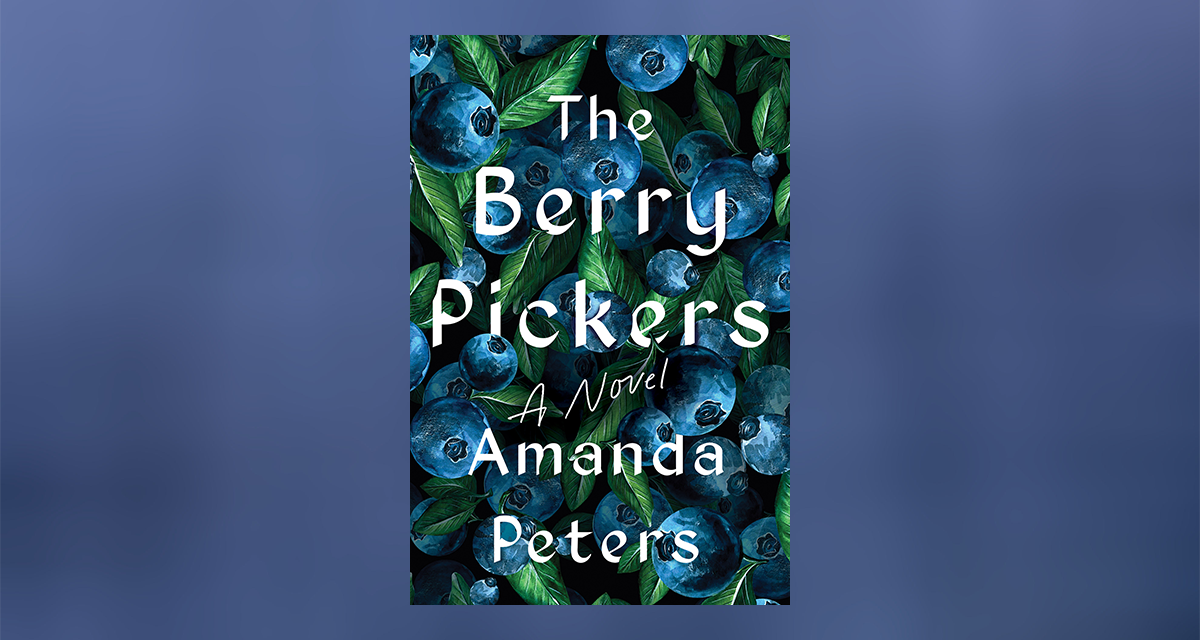

July 1962. A Mi’kmaq family from Nova Scotia arrives in Maine to pick blueberries for the summer. Weeks later, four-year-old Ruthie, the family’s youngest child, vanishes. The mystery of her disappearance will haunt the survivors, unravel a family, cast a shadow of trauma over the community, and demonstrate the persistence of love across time in the fifty years that follow.

The Berry Pickers is a debut novel about the search for the truth, the shadow of trauma, and the persistence of love across time by Mi’kmaq author Amanda Peters.

“A harrowing tale of Indigenous family separation. . . . [Peters] excels in writing characters for whom we can’t help rooting. . . . With The Berry Pickers, Peters takes on the monumental task of giving witness to people who suffered through racist attempts of erasure like her Mi’kmaw ancestors.” —The New York Times Book Review

The day Ruthie went missing, the blackflies seemed to be especially hungry. The white folks at the store where we got our supplies said that Indians made such good berry pickers because something sour in our blood kept the blackflies away. But even then, as a boy of six, I knew that wasn’t true. Blackflies don’t discriminate. But now, lying here almost fifty years to the day and getting eaten from the inside out by a disease I can’t even see, I’m not sure what’s true and what’s not anymore. Maybe we are sour.

Regardless of the taste of our blood, we still got bit. But Mom knew how to make the itching stop at night, so we could get some sleep. She peeled the bark of an alder branch and chewed it to a pulp before putting it on the bites.

“Hold still, Joe. Stop squirming,” Mom said as she applied the thick paste. The alders grew all along the thin line of trees that bordered the back of the fields. Those fields stretched on forever, or so it seemed then. Mr. Ellis, the landowner, had sectioned the land with big rocks, making it easier to keep track of where we’d been and where we needed to go. But eventually, and always, you’d reach the trees again. Either the trees or Route 9, a crumbling road littered with holes the size of watermelons and as deep as the lake, a dark line of asphalt slithering its way through the fields that brought us there year after year.

Even then, in 1962, there weren’t many houses along Route 9, and those that were there were already old, the grey and white paint peeling away, the porches tilted and rotting, the tall grass growing green and yellow between abandoned cars and refrigerators, their rust flaking off and flying away with a strong wind. When we arrived from Nova Scotia, midsummer, a caravan of dark-skinned workers, laughing and singing, travelling through their overgrown and rusting world, the local folks turned their backs, our presence a testament to their failure to prosper. The only time that place showed any joy at all was in the fall when the setting sun shone gold and the fields glowed under a glorious September sky.

Copyright © 2023 by Amanda Peters. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

AMANDA PETERS is a writer of Mi’kmaq and settler ancestry. Her work has appeared in the Antigonish Review, Grain Magazine, the Alaska Quarterly Review, the Dalhousie Review and Filling Station Magazine. She is the winner of the 2021 Indigenous Voices Award for Unpublished Prose and a participant in the 2021 Writers’ Trust Rising Stars program. A graduate of the Master of Fine Arts Program at the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico, Amanda Peters has a Certificate in Creative Writing from the University of Toronto. She lives in the Annapolis Valley, Nova Scotia, with her fur babies, Holly and Pook.