By: Dr. Ron Lee, Associate Professor, Political Science; Chair, Department of Political Science, Sociology, and Criminal Justice; Director, First Year Seminar Program at Rockford University

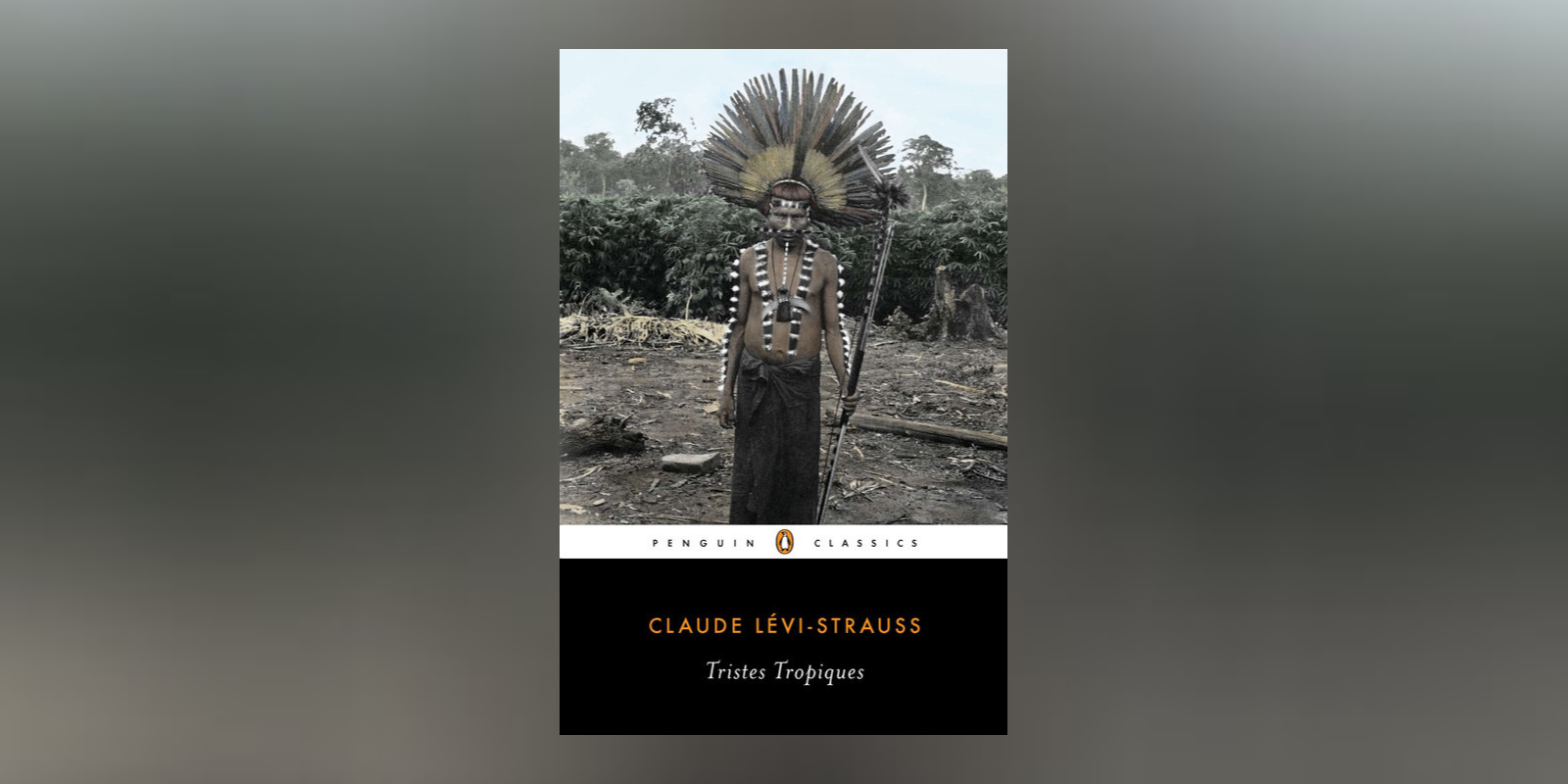

In an age defined by its great enthusiasm for diversity, a serious concern with the differences between us requires that we advance our understanding of those differences beyond a merely superficial celebration of cultural diversity. Indeed, any deep exploration of differences that is worthy of the name should be undertaken with the hope or expectation that the search is of vital importance. It is difficult to think of a more serious purpose for exploring differences among communities and ways of life than the desire to develop in oneself or another the freedom from narrowness and prejudice that defines anyone who has had no contact with or understanding of communities or people other than one’s own. It is with this intent to help open my students’ minds to forms of community and ways of life significantly different than our own that I have assigned in my introduction to international studies course Claude Lévi-Strauss’ seminal anthropological study, Tristes Tropiques.

Mark Twain famously defined a classic as “something that everybody wants to have read and nobody wants to read.” And this would aptly apply to Lévi-Strauss’s classic. But it has been my experience in teaching this book that if given a compelling reason for reading it and if provided lots of guidance to aid in drawing meaning from it, students are intrigued by and even come to appreciate this wonderful book and the entirely new world it opens up for them.

A few words about the course as a whole. It is an introduction to the principal issues, perspectives, and modes of inquiry in the field of international studies. Drawing on the social sciences and humanities, this course is both multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary, helping students see how different fields of study approach problems and questions, as well as how different disciplines connect with one another, or contradict one another, concerning methods and goals. Through course readings and class discussions students gain an international perspective and an understanding of some of the most fundamental issues facing the world today.

A principal theme in the course is the meaning of cultural identity in a multicultural context, thus, the problem of identity when culture encounters culture. Richard Rodriguez’s Hunger of Memory, Tzvetan Todorov’s Conquest of America, and Charles Taylor’s “The Politics of Recognition” put this theme forward, and these texts are the primary focus in the first part of the course. We begin by thinking about the socio-political context for personal identity and its relationship to public life through an examination of Hunger of Memory. We move from Rodriguez’s interpretation of cultural identity in contemporary America to the Americas of the 15th – 17th centuries. Todorov’s Conquest of America looks at the interactions of the peoples of two great civilizations: the conquistadors of Spain and the native peoples of Central America. Todorov asks us to think about how the encounter of these civilizations influences the lives and identities of both the conquerors and the conquered. These cases draw us into a discussion of the transcendence of particular ethnic or cultural identities, the formation of hybrid identities, and the possibilities for multi-cultural and/or assimilative policies. Through the essay “The Politics of Recognition” we take up the arguments of Charles Taylor regarding cultural/national identities in liberal democratic states. The debate on multiculturalism forces us to think about whether it is possible or desirable to maintain distinct cultural and ethnic identities within liberal democracies and whether liberalism is compatible with nationalism. We then return to the idea of cultural confrontation with a reading by Samuel Huntington on the contemporary “clash of civilizations.” Is “the West” with its multicultural, liberal democratic regimes in conflict with other types of civilizations? How are our identities shaped by our civilization, our political system, our religious beliefs? How does the contemporary clash of civilizations compare to the conflict between conquistadors and natives? What does the clash of civilizations in the historical and contemporary Americas mean for our identities as U.S. citizens? Do cultures seek to remain distinct and different from others? Or is the contemporary era of globalization producing hybridized individuals and societies? Are distinct cultures and nations coming to an end? If so, what will they be replaced by? Kenichi Ohmae takes up these issues in his article, “The Rise of the Region State,” examining the impact of the global economy on civilizations and nations.

The second part of the course concentrates on one key aspect of modern cultural identity: the encounter between global, scientific culture found in the West and tribal cultures. A Pew Research Center report gives us insight into how Americans feel about the satisfactions and stresses of modern life. The 18th century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau makes the case in his Discourse on Inequality that primitive or tribal culture was a healthier and happier alternative to that of our own professional, technological society. We then put Rousseau’s claim to the test by means of a famous anthropological study of Amazon tribes by Claude Lévi-Strauss and finally through the fiction of a West African writer who grew up in a tribal culture, Chinua Achebe.

Parts V, VI, VII, VIII, and IX are the most essential parts of the text, it seems to me, for a more general reader as here is where one finds the heart of Levi-Strauss’s book, the rich details of the tribal communities he describes.

Dr. Ron Lee has taught at Boston College, Michigan State University, and Kenyon College. He recently published a piece in the University of Illinois Law Review Online. His work has also been published in the political science journal Polity. He edited and was a contributing writer for high school readers on American government, the Constitution, American history, and world politics. His teaching and research interests include the history of political philosophy, the American presidency, and the principle and practice of American foreign policy.