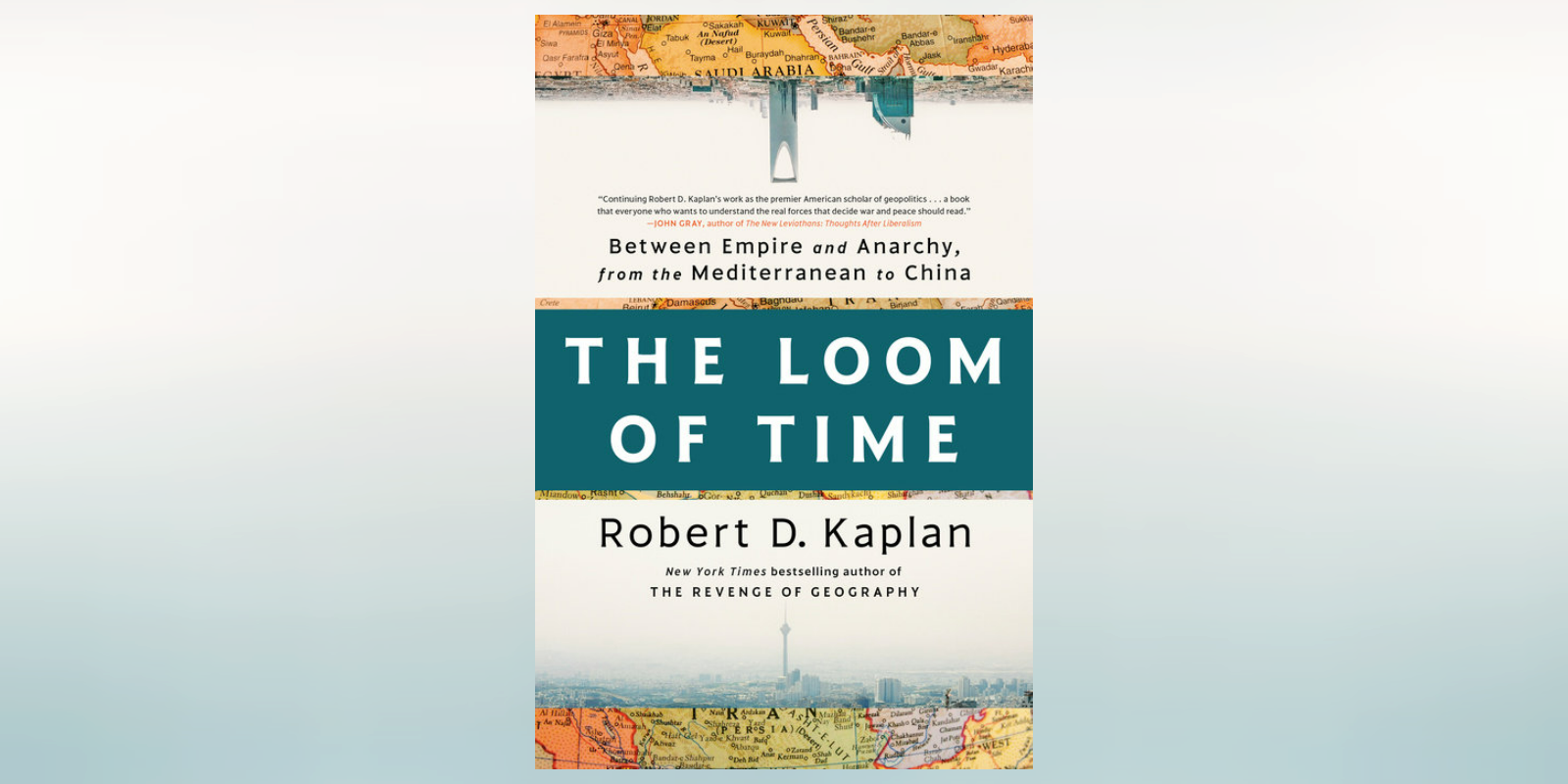

From The Revenge of Geography author Robert D. Kaplan, The Loom of Time is a stunning exploration of the Greater Middle East, where lasting stability has often seemed just out of reach but may hold the key to the shifting world order of the twenty-first century.

Chapter 1

Time and Terrain

Between Europe and the great, mature civilizations of China and India lies a belt of over three thousand miles, dominated by desert and stony tableland, where rainfall is relatively little, frontiers are contested, political unity has rarely existed, and where, as the late Princeton historian Bernard Lewis claimed, there has been no historical pattern of authority. Lewis’s generalization is imperfect, to be sure. Egypt and Iran, it could well be argued, were mature civilizations for thousands of years, as were Iraq and Turkey. Nevertheless, there is a point to be made regarding the general aridity, sheer variety, and political tumult in the lands between the Mediterranean and China. It is this austere landscape that constitutes the “Land of Insolence,” declared mid-twentieth-century American anthropologist Carleton Coon, referring to the rebellious nature of modern Middle Eastern politics, with its tradition of pride and independence that combines with tribalism and ethnic and sectarian tensions. Coon’s phraseology is especially quaint and deterministic, particularly since tribalism has kept the peace within large groups, and in other ways is not the altogether divisive factor the West thinks it is. Nevertheless, Coon’s phrase has an undeniable resonance, owing to the indisputably high level of violence and political instability in this yawning region compared to other parts of the globe. For example, a significant part of the population of the Arab world has experienced violent anarchy in recent decades, and according to a U.N. report, though Arabs account for only 5 percent of humanity, they have generated 58 percent of the world’s refugees and 68 percent of its “battle-related deaths” in the second decade of the twenty-first century. Indeed, the maturation from medieval kingdoms to early modern states, and then to modern democratic states, as happened in Europe, or of the successive, millennia-long drumroll of elaborate dynastic empires as in China and the Indian subcontinent—places with lusher, more habitable landscapes—do not obtain to the same degree in the vast and thin-soiled battlefield of different cultures and civilizations that sweeps across the southern rimland of Eurasia, too often disunited by a singular religion rather than united by it. Keep in mind, however, that the tragedy of the Greater Middle East ever since the collapse of the Ottoman Empire has as much to do with the West’s dynamic interaction with it as with the region itself, as we shall see later on.

But first, back to the essentials.

The very question of political authority—of who controls whom—has often been unsettled across the Middle East. Islam, revealed by the Prophet Muhammad, a trader in the richly cosmopolitan crossroads of Mecca at the beginning of the seventh century a.d., was concerned with ethics and how to live a pure and just life against the demanding limitations of a desert landscape, where the environment was treacherous and travel consequently difficult. Here aridity had created oases that served as “juncture points” across the desert, spurring trade, and thus Islam was a boon to honest-dealing. Though the new religion offered a complete way of existence that spanned civilizations and over the centuries made millions of impoverished people content with their lives, as Coon was one of the first outsiders to observe, it left no sturdy provision for temporal political authority. That is to say, whereas other religions, such as Christianity, did not seek control over politics, but generally limited themselves to private belief, Islam offered a complete way of existence. Olivier Roy, the French academic and political scientist, writes that “Islam was born as a sect and as a society,” but without institutions or even a clergy to organize it. Indeed, the great linguist and area specialist of the Sorbonne, the late Maxime Rodinson, called Islam “not only an association of believers,” but a “total society.” And as a total society—encompassing the heretofore secular world—Islam required but often crucially lacked, as Roy puts it, a philosophy of political organization.

Because Muhammad offered an utterly new and purer interpretation of existence that would replace the previous social contract, he was naturally met with opposition. When he and his followers left Mecca because of its hostility to the new creed and fled northward to Yathrib (Medina, “the city”), they essentially founded a new community. Significantly, the Islamic calendar begins not with Muhammad’s birth or even with the beginning of his revelation, but with this migration, or Hegira. This new community was for all intents and purposes revolutionary. And in the Arab and Islamic worlds it would consequently breed over the centuries and millennia dynastic upheavals and other revolutions having to do with sect, ambition, legitimacy, and purity. The very rise and fall of dynastic empires, and the political dramas within them, across the Middle East often had to do with the intersection of religion and politics. Sayyid Qutb, the Egyptian intellectual and Muslim Brotherhood leader, famously used this argument to attack the impure, pagan (kafir) system of Gamal Abdel Nasser, who would have Qutb executed by hanging in 1966.

Ever since the first half century of Islam’s founding, authority has been disputed and struggles have ensued over the leadership of the faith, with Sunnis, Ibadis, and Shi’ites—and the various offshoots of Shi’ism such as Zaidis, Isma’ilis, Alawites, Druzes, and so on—all maintaining different theories of spiritual governance, in a way not so dissimilar to Christianity. Political legitimacy was very difficult to come by. This became true not only at the state level, but at the level of the town and tribe, and within tribes, so that many a place was divided between “Arabian Montagues and Capulets,” in the words of the Oxford-trained Arabist Tim Mackintosh-Smith. Particularly after the collapse following World War I of the Ottoman Empire, which had led the Islamic world in the Middle East for at least half a millennium, there have been bloody struggles over the inheritance of power, leading to a contest over which group could claim to be the purest in doctrine, and sometimes by inference the most extreme, a tendency that has had its similarities with medieval Christianity. The corollary was the 1978–79 Iranian Revolution, the various offshoots of Salafism, and particularly ISIS: making for a Grand Guignol of violence and breathless headlines with which we have all become depressingly familiar.

This, then, is the Greater Middle East, broadly speaking the Islamic world of the desert and plains (as opposed to the Indian Ocean world of seafaring Islam), a vast swath of the earth where I have spent the past fifty years traveling and reading about: stretching from Morocco in the western Mediterranean to East Turkestan, abutting the arable cradle of China; or from the Eastern Orthodox Balkans south to the mountainous monsoon land of Yemen; or, by yet another measure, from the violent anarchy of Libya to that of Afghanistan. It is an area that the Greeks referred to as the oikoumene, meaning the inhabited part of the globe that the Greeks knew and knew of. The oikoumene was an idea more than a geography. A concept much larger than the arid zone of the Arab world, it included Ethiopia, Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, the Caucasus, and Central Asia, and featured an interconnectedness that constituted an early form of globalization. This is the same map largely traversed by Herodotus and Alexander the Great. It is often the most antique and storied places that have provided the datelines for the worst modern horrors.

For example, witness Palmyra. Lodged in my memory of decades ago are its slender Corinthian columns punctuating the horizontality of the Syrian Desert. Here the “Queen of the East,” Zenobia, a far more substantial figure than Cleopatra, was finally subjugated by the Roman emperor Aurelian in a.d. 272. Aurelian burnt the city down a year later. Palmyra would be subjugated once again and have much of its greatest antiquities mutilated and destroyed by ISIS between 2015 and 2017. It was a seminal crime against sacred objects of the past, confirming the group’s nihilistic violence against human beings.

What is the direction of it all? What political dimensions will this vast region located largely in the subtropics between Europe and the Far East ultimately assume? Might it emerge out of decades of instability and bad governance to find a crucial middle ground between tyranny on one hand, and anarchy on the other?

The answers begin with a perspective across the chasm of the decades and centuries.

To explore that distance so far beyond the scope of human comprehension, as well as other questions, requires the help of not only contemporary experts but also writers long out of fashion. For while the values of those deceased writers may not measure up to our own, their brilliance is undeniable, the reason why their works have been judged as classics in the first place. Thus, we should be humble regarding previous ages of scholarship, which, flawed as they may be, provide the foundation for our own.

So let us begin.

Copyright © 2023 by Robert D. Kaplan. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

© John Stanmeyer

Robert D. Kaplan is the bestselling author of twenty books on foreign affairs and travel translated into many languages, including Adriatic, The Good American, The Revenge of Geography, Asia’s Cauldron, Monsoon, The Coming Anarchy, and Balkan Ghosts. He holds the Robert Strausz-Hupé Chair in Geopolitics at the Foreign Policy Research Institute. For three decades he reported on foreign affairs for The Atlantic. He was a member of the Pentagon’s Defense Policy Board and the U.S. Navy’s Executive Panel. Foreign Policy magazine twice named him one of the world’s “Top 100 Global Thinkers.”