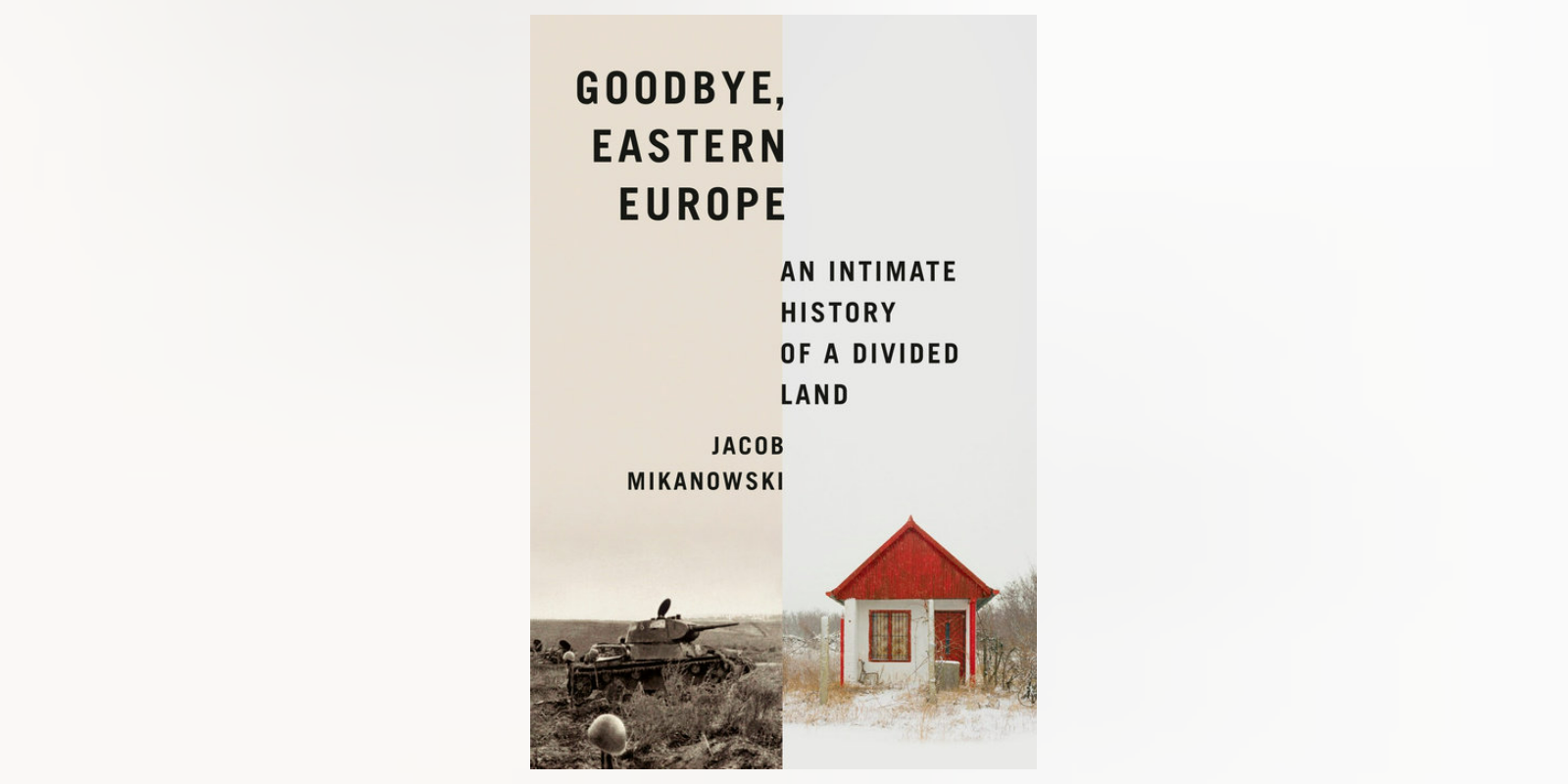

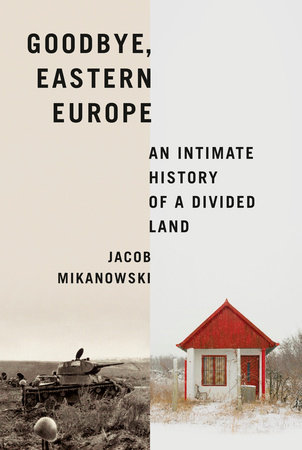

Goodbye, Eastern Europe is a crucial, elucidative read, a sweeping epic chronicling a thousand years that illuminates the remarkable cultural significance and richness of a place perpetually lost to the margins of history.

Part I

Faiths

1

Pagans and Christians

A great forest, bristling with dangers and the occasional gleam of treasure: that is how the territories of Eastern Europe must have appeared to the average Roman in the time of the emperor Marcus Aurelius. To them, the lands north of the imperial frontiers were largely a mystery. Marcus himself traveled north of the Danube in A.D. 170, to fight a war against a confederation of barbarian tribes. He began writing his Meditations there, camped out with his soldiers by the banks of the River Hron, in what is now Slovakia. This work, a classic of Stoic philosophy, might be the first piece of literature written in Eastern Europe. Marcus did not mention his surroundings even once, but that should not strike us as too surprising. The territories north of the Roman Empire were empty of cities, writing, temples, or any of the other markers that would have indicated the presence of civilized life to someone arriving there from the shores of the Mediterranean. As far as the Romans were concerned, these cold and rather frightening lands were sources of two things and two things alone: inexhaustible hordes of enemies, and a lightweight precious stone called electrum, or amber.

I used to have a cigar box that belonged to my grandfather. It was full of the rough orange pebbles of raw amber that he had gathered with my father on Polish beaches. All along the shores of the southern Baltic, from Denmark to Estonia, amber is just that easy to find: you just have to go to the beach after a storm, or know where to dig in the sand. The routes that brought this precious stone, so mysteriously radiant and light, to the shores of the Mediterranean were already old by the time Marcus Aurelius arrived. A century earlier, during the reign of the emperor Nero, a Roman knight had set out north from a frontier post in what is now Austria. He had orders to bring back as much amber as he could buy; the emperor needed it to decorate his new Colosseum. The knight traveled north hundreds of miles, to the shores of the Baltic. To everyone’s amazement, he returned with wagonloads of the stuff, pieces the size of pumpkins, enough to decorate the whole amphitheater, down to the knobs on the nets that protected spectators from the wild animals raging within.

The trade in amber between the Baltic and the Mediterranean dates back at least to the Bronze Age. But in this case, commerce did not foster connection. These voyages left only the faintest mark in Eastern Europe—at most, a few fragile traces: buttons from an equestrian’s uniform found next to a Polish lake, a cavalry helmet in a Lithuanian tomb. And Roman coins—a profusion of coins. These were not used as money in the countries in which they were received. They were treasure in a truer, purer sense—tokens from another world. In the Russian enclave between Poland and Lithuania (an area that’s especially rich in amber), there are ancient cemeteries in which every grave contains at least one shiny brass sestertius. These coins were placed next to the head of the deceased, in vessels made from the bark of the sacred birch tree, intended as payment for a Baltic ferryman to the underworld whose name has been lost to time.

A flash of silver unearthed by a plow: that is how the ancient world appears in most of the countries of Eastern Europe. Otherwise, silence. History arrives only with the advent of Christianity and, with it, the written word. Before then, we know hardly anything for certain. Here, the Dark Ages were truly dark: north of the old Roman frontier, almost impenetrably so. But even to the south, the gloom is difficult to penetrate. When the Slavs arrived, in the desperate decades of war, famine, and plague that followed the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, they seemed to come from nowhere, and then, all of a sudden, to be everywhere at once.

Today Slavic languages are spoken in a vast chunk of Europe, from Bulgaria and the former Yugoslavia in the south to Poland and all of Russia to the north. This is a vast territory, but only some of it seems to have been inhabited by Slavic-speakers from an early date. The first mentions of the Slavs in ancient sources came toward the end of the sixth century. By the year 1000, they were present everywhere from northern Greece to the edge of Finland.

But where did the Slavs come from? This question vexes historians, since it has no solution but many competing claims. For many decades, the answer depended on who you were. Russians insisted that the Slavs came from Russia, Ukrainians said they came from Ukraine, and Poles said they came from Poland. Then for a time, a loose consensus emerged placing the Slavic homeland in Polesia, a region of endless wetlands stretching along the length of the border between Ukraine and Belarus. I used to imagine them emerging out of a bog wearing great leather waders, with water dripping down their mustaches, ready to conquer Thessaloniki as soon as they toweled off.

This is no longer the preferred view. Today, the cutting-edge theory is that the Slavs came from what is now Romania, rather paradoxically, since there are no Slavic-speakers there today (Romanian is a Romance language). According to this interpretation, they coalesced as a result of the Eastern Roman Empire’s bottomless need for manpower to staff the forts lining the Danubian frontier. There is much to recommend this view, but we will never know for sure. The early Slavs had few notable leaders and no great chroniclers. They came not as a flood but in a series of smaller streams. In the words of one historian, theirs was an “obscure progression,” visible only in sporadic moments, illuminated by a dull and flickering flame.

A similar murkiness clings to Slavic beliefs. We know very little about their mythology or rituals—only that they were pagans and worshipped a pantheon of gods. But when the Christian priests arrived to drive out the old ways, no one thought it worthwhile to record them. One of the paradoxes of religious history in Eastern Europe is that paganism lasted so long there, yet we know so little about it. There is no Slavic equivalent to the great compendium of Norse myth preserved in the Icelandic Edda, or the Celtic tales contained in the Welsh Mabinogion or the Irish Táin. All we have are fragments, recorded by hostile witnesses.

One of the first such testimonies comes from, of all places, Sicily. Around A.D. 700, a Slavic raiding party was taken prisoner by the local militia. An enterprising bishop asked its members what they believed in. By means of a translator, they replied that they worshipped “fire, water, and their own swords.” Almost seven hundred years later, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was still being ruled by practicing pagans who believed something very similar. A vast realm that incorporated much of today’s Belarus and Ukraine, Lithuania was the last country in Europe to give up the old faith. In 1341, when Grand Duke Gediminas died, he was buried in the full, cruel splendor of the pagan rite: burned to ash on a giant pyre, along with his favorite weapons, slaves, dogs, and horses, and a few German Crusaders thrown in for good measure. When the whole thing caught fire, Gediminas’s fellow pagan lords cried out in sorrow and pelted the flames with the claws of lynxes and bears.

Two hundred years later, hardly anything of this pagan faith remained. At most, Polish and Lithuanian chroniclers could recall a few hallowed names. During the Renaissance, humanist scholars amused themselves by inventing ever more elaborate pantheons for their pagan ancestors. To the old gods of thunder, cattle, and grain, they added deities in charge of hogs and wives, a god (and goddess) of beekeeping, as well as humbler spirits to watch over everything from hazelnuts to yeast.

None of these, of course, were genuine. Almost everything that has ever been written about the ancient religion of the Balts and Slavs is false. Most of it is based on a few late observations and the testimonies of outsiders. Beyond the names of a few deities and a few scant archaeological remains, nothing is clear. So what can we say about these gods with certainty? Only three things: they lived in trees, they spoke through horses, and they savored the smell of freshly baked bread.

The paganism of the Balts and Slavs was an “outdoor religion.” The forest was its true temple. Most shrines were simply groves, or great trees that held special renown in and of themselves. On an island in the River Dnieper there stood a huge oak tree that passersby honored with sacrifices of arrows, meat, and bread. Until recently, women in Polesia still offered specially baked bread to the setting sun every Easter, and they prayed before a sacred tree to ensure a good harvest. This echo of a thousand-year-old custom lasted until 1986, when the Chernobyl disaster tainted the land and drove its inhabitants to seek refuge elsewhere.

The pagan Prussians (a Baltic people who predated the Germans in what would become East Prussia) worshipped in groves of holy oak trees. Each grove had its own priests and sacrifices. It was a meeting place, a sanctuary, and an oracle. While the cult of the gods was still alive, its adherents would ask the trees and the lakes they worshipped questions, most often about their enemies. Gods spoke through the landscape they inhabited, but the easiest way to ask them a question directly was to seat their spirit astride a horse. When the Slavs who lived by the mouth of the Oder River considered going to war, they would consult a sacred horse by walking it past a series of spears planted in the ground. If the horse left the spears alone, they rode to battle.

As Christianity drew ever nearer, the pagans of the southern Baltic had many occasions to ride to war. For two centuries, from roughly 1200 to 1400, the southeastern shores of the Baltic played host to a bloodthirsty Christian Crusade. It was led by the Teutonic Knights, an order of (mostly) German knights, freshly returned from the Holy Land, searching for a new arena in which to fight a holy war. From northern Poland to Estonia, they preached the word of God with “tongues of iron,” to borrow a phrase from Charlemagne. Everywhere the fighting was brutal. In Prussia, it amounted to a war of extermination that ended with the disappearance of the Prussians as a people and the extinction of their language.

Here Christianization really amounted to a form of colonization. In a foretaste of what would happen one day in the New World, the whole social system of medieval Europe was transplanted to the east by force. Eastern European paganism was a local religion, intimately tied to place. Its laws stretched only as far as the course of a single stream or the shade of a certain tree. Christianity, by contrast, was a missionary faith. It tried to remake the whole world in its image. It attacked in waves. First the missionaries came to cut down the holy groves. Then came the Crusaders to break the power of the ancient chiefs and massacre their followers. When their work of slaughter was done, Christian landowners arrived to reduce the baptized survivors to the status of serfs.

The Chronicle of Henry of Livonia is our best source for what this war must have felt like to those involved. Henry was a Saxon priest attached from an early age to the household of Bishop Albert of Buxhoeveden, one of the leaders of the conquest of what is now Latvia. In 1200 Albert set out from Hamburg with a fleet of ships and soldiers and landed on the site of present-day Riga. This was to be Albert’s bishopric, if he could conquer and convert it.

Henry’s Chronicle is the story of this conquest. It is told in the first person, covering two decades in the lands that are now Latvia and Estonia. His story is set among virgin woods, frozen rivers, and deep snows. It is punctuated by terrible violence: beheadings, behandings, disembowelments. Men are burned alive, and their hearts eaten to gain their owners’ life force. Even among the converts to Christianity, things are touch-and-go. As soon as the Christian fleet that converted them leaves, one group of pagans plunges into the nearest river to scrub off the baptism they just received. They then cut down what they take to be the idols of the Christians and set them afloat on a raft to join their departed masters. Elsewhere, in Estonia, pagans revolted and threw off the rule of the priests. Immediately they rushed to the churchyards, dug up their dead, and incinerated them according to their ancient custom.

The old cult of the trees proved to be especially difficult to eradicate. In Estonia, when priests razed the lovely forest dedicated to the god Tharapita, the locals were amazed that the trees didn’t bleed like human beings. In northern Poland, when missionaries tried to do the same thing, the Prussians cut off their heads. In Pomerania, near the border between Poland and Germany, the local tribes considered two trees especially sacred: a gorgeous old nut tree, and a gigantic leafy oak with a spring beneath it. The pagans managed to convince the priests to spare them from being cut down by promising to convert. They solemnly swore that from then on, they would never worship the trees again; they would simply rest in their shade and savor their beauty.

For all the violence wielded by the Crusaders, the old ways never fully went away but were driven underground, or else they found Christian disguises. In some places, pagans made a deal with their conquerors to keep their traditions intact. In western Latvia, a group of local free farmers who came to be known as the Curonian Kings struck a bargain with the Teutonic Knights. In exchange for help fighting their pagan brethren, the Kings were granted two privileges. The first was that they could keep cremating their dead, a habit long denounced by the Christian friars. The second was that they didn’t have to chop down their holy grove. This forest, shared in common by seven villages, was kept inviolate. No brushwood could be gathered there, and hunting there was allowed only once a year, at the winter solstice. All the game taken then was shared in common at a great feast, at which great quantities of beer were drunk and the dancing continued through the night. This was a wild hunt, whose trophies belonged to the gods.

Traces of the specific forest where the Curonian Kings held their feast remain to this day. One fragment, called the Elka Grove, is located a few miles south of the town of Kuldīga, in Latvia. Deep into the twentieth century, it was still prohibited to light fires or break branches in this once-sacred grove. Anyone who violated the taboo risked causing either a fire or a death. However, after a funeral in the village, the rule was reversed.

Copyright © 2023 by Jacob Mikanowski. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

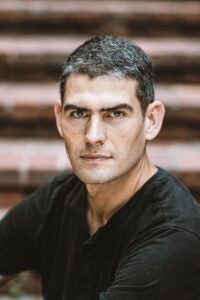

JACOB MIKANOWSKI is a historian, a freelance journalist and a critic. His writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Aeon, Cabinet, The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Guardian, The New York Times, newyorker.com, The Point, The Awl, Atlas Obscura, Slate and the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. He lives in Berkeley, CA.

JACOB MIKANOWSKI is a historian, a freelance journalist and a critic. His writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Aeon, Cabinet, The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Guardian, The New York Times, newyorker.com, The Point, The Awl, Atlas Obscura, Slate and the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. He lives in Berkeley, CA.