By: Gabel Strickland

“More than a little like Robin Hood, the mythic outlaw but friend of the people who has endured like no other figure in the English language, the pirates—to simplify an exceedingly complex category—have been a natural for popularization and romanticization. They exist beyond the margins of law and order. They boast and sing lustily about their lives on the sea and off. By progressive or radical interpretation, they sometimes join directly in the struggle of the dispossessed, but more than often the struggle for the survival of themselves, outcasts of any age.” —Paul Buhle, afterword of Under the Banner of King Death

The proud subversiveness of a pirate’s lifestyle often makes them a heroic figure for the marginalized. For the politically, socially, and economically oppressed, pirates are a vessel (get it?) through which to see their own liberation, representation, and revolt against the powers that be. At sea, the enslaved can be free, the disenfranchised can vote, people can even create new identities—and legends—around themselves.

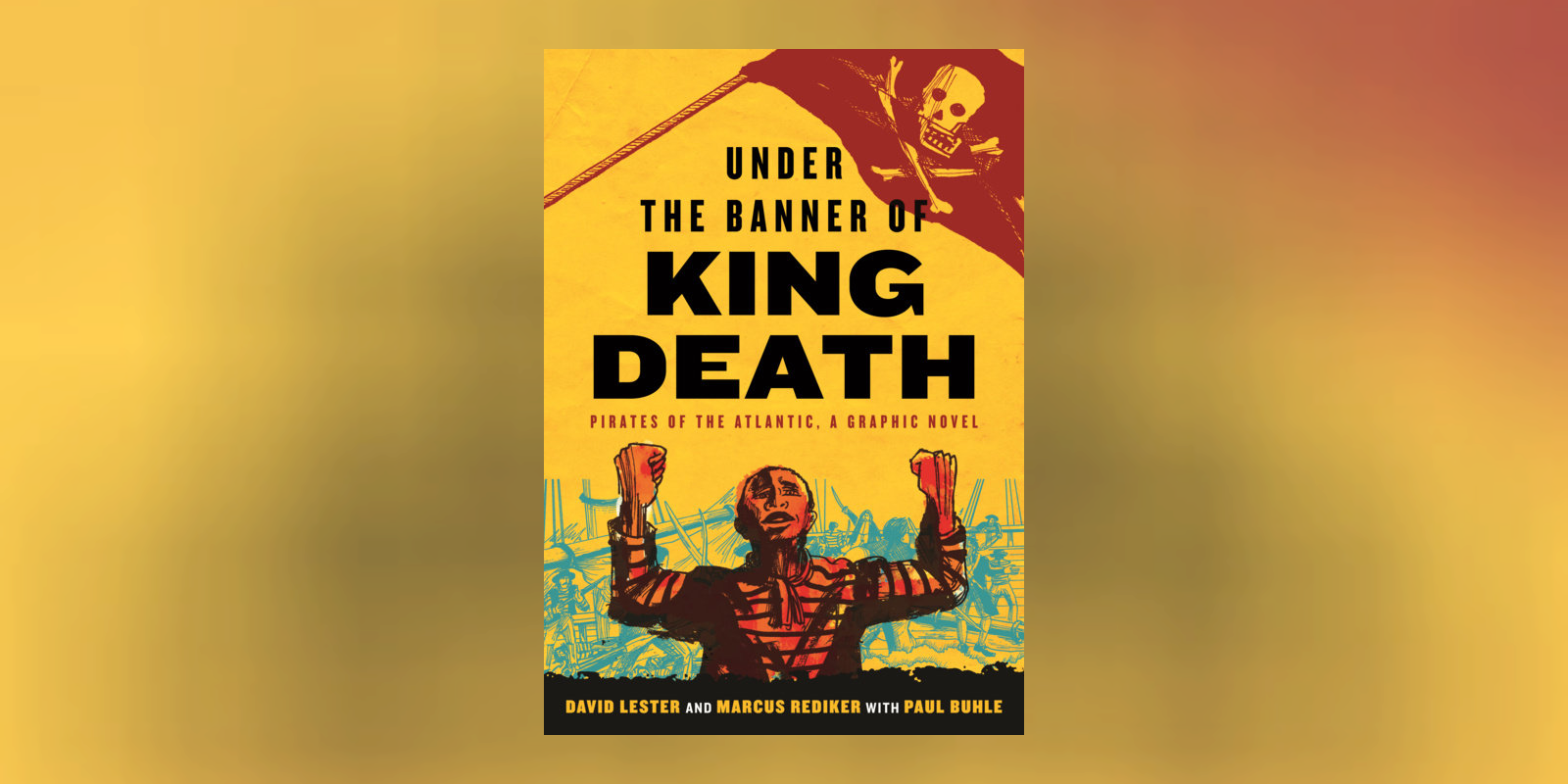

This idea is reflected in today’s newest and most popular pirate media. Under the Banner of King Death, written by Marcus Rediker, illustrated by David Lester, and edited by Paul Buhle, dramatizes how piracy allowed lower class men (and women) to meaningfully participate in democracy and for formerly enslaved people to find freedom on the high seas. This graphic novel’s protagonists, John Gwin, Ruben Dekker, and Mark/Mary Reed, overthrow their ship’s captain to embark on a voyage of revelry and mayhem. Comparatively, HBO’s popular television series Our Flag Means Death tells the story of how a fictionalized version of Stede Bonnet uses piracy to escape the toxic masculinity and societal expectations that burden him back home. He becomes The Gentleman Pirate, exploring his queerness on the open seas with his eventual lover, Blackbeard.

Both stories explore how pirate narratives can be the perfect medium through which to provide empowering, empathetic representation of marginalized voices as well as provide social and political commentary. Let’s compare the two.

Representation and Critique of Oppressive Systems

Pirates flee from society and all its oppressive structures—from capitalism, from the authority of the government, from the very ground these structures are built upon. So naturally, for characters of marginalized identities, piracy is a way of blatantly rejecting the institutions that confine them on land. Both stories explore this concept, but each show focuses on representing different marginalized identities. In Under the Banner of King Death, John Gwin escapes the confines of racial hierarchies. In Our Flag Means Death, Stede Bonnet (and other characters) freely explore queerness from beyond the jurisdiction of society.

Let’s start with Under the Banner of King Death. John Gwin escapes slavery in South Carolina by fleeing to the open seas. Gwin has been successfully seafaring for some time when, at the beginning of the graphic novel, he and his companion, Ruben Dekker, are forced to work on a slave ship called “The African Prince.” Eventually, he leads a mutiny against the ship’s captain, freeing the people trapped in the ship’s bowels and entering his life of piracy. This life allows him to literally and metaphorically break the chains of his bondage. From then on, Gwin makes his own decisions, travels wherever he pleases, and even falls in love with a white woman, Mary Reed. None of this would have been possible on the plantation in South Carolina.

Mary Reed is also afforded a unique freedom on a pirate ship, where she spends most of her time disguised as a man, Mark Reed. Seafaring ensures her the personal autonomy that would never have been afforded to her in England, where women were continually denied even the most basic personal and political liberties.

For Our Flag Means Death’s Stede Bonnet, escaping society means escaping the heteronormative, toxically masculine social structure at the heart of English life. On his own ship, Bonnet gets to be unabashedly himself—flamboyant, silly, gentle—without enduring the mockery of his father and peers for not being “masculine” enough. The pirate life is also how he escapes his loveless marriage with Mary Bonnet and discovers his love for Blackbeard.

Similarly, piracy (unexpectedly) affords other characters opportunities that they would not have had otherwise. Jim, a nonbinary character, at first hides in the system of piracy, but eventually, establishes their own genderfluid identity aboard. Episode four is key in this. When a member of the crew asks Jim, “So this whole time you’ve been a woman?” Jim says, “I don’t know.” Jim leverages the already unregulated life of a pirate ship to create a new name and life for themselves, asserting their identity through sheer force. Later, the crew begins referring to Jim with multiple different pronouns, mostly they/them. Surprisingly, even Bonnet’s abandoned wife Mary finds her own means of empowerment in her husband’s absence. Without a husband to answer to, she finds social belonging in a group of other “widows,” starts a flourishing art career, and even explores her own sexuality with a new lover. So goes the domino effect of one person choosing a life beyond society’s rules and land.

Depiction of Democracy on a Pirate Ship

There are several aspects of pirate life that intrigue Marcus Rediker, one being the democracy pirate crews enjoyed at a time when much of the world lived under the rule of a monarch. Rediker is a scholar of Atlantic history and the author of Villains of All Nations, a social and cultural history of the Golden Age of piracy that inspired Under the Banner of King Death.

As Rediker said in an interview with Asia Art Tours in 2021, “At a time when poor people had no democratic rights whatsoever (the early 1700s), they elected their officers and limited their power. At a time of extreme inequality, they divided their loot and resources in stunningly egalitarian ways. These practices were direct and subversive attacks on how merchant and naval ships operated—and the ruling classes of the Atlantic immediately understood them as such.”

This democratic system is displayed in Under the Banner of King Death. After John Gwin leads his crew in overthrowing their ship’s original captain, he oversees a vote in which the crew collectively decides where they should sail next.

Our Flag Means Death also highlights this emphasis on giving each crew member equals rights and decision-making power. In episode one, Stede Bonnet encourages each crew member to sew a new flag for the ship, declaring that the crew will vote on the best one afterwards. Even as Bonnet asserts the importance of this egalitarianism, the show demonstrates the crew’s power over their leadership in another way: in the same episode, the crew plots to overthrow Bonnet as captain, deciding amongst themselves what they demand of their leader and who should replace Bonnet once he is deposed. The message is clear: the crew always has a say over the ship’s operation, whether the captain embraces that power or not.

Historical Accuracy

Both Under the Banner of King Death and Our Flag Means Death are fictionalized stories rooted in historical fact, situated during the same historical period (the early 1700s, the Golden Age of Piracy). Therefore, they touch on many of the same historical elements of pirate life: the rivalry with the British naval ships, the depiction of pirate life itself, interactions with Indigenous populations of various lands, etc. However, it is in their characters that these pirate tales show the most creative freedom in interpreting—or even directly rewriting—history. Both narratives have a blended cast, some characters being entirely made up and others being based on people who really lived. When writing the latter, they stick to the broad, well-known plot points in their characters’ real lives while also taking plenty of artistic liberties for the sake of the story.

For example, the crew of Under the Banner of King Death is fictional. John Gwin and Ruben Dekker are both made up to tell this story. Mary Reed is the only character who is historically documented (in real life, her name is spelled Mary Read). However, David Lester and Marcus Rediker plucked Read from her documented story and recast her into this one. The graphic novel stays true to selective elements of her past. It is true that Read lived in disguise as a man on her pirate ships. It is also reported that she was pregnant when she was captured, which stalled her execution. However, her voyage with Gwin and Dekker’s crew is entirely invented.

Similarly, while it is documented that Stede Bonnet and Edward “Blackbeard” Tatch sailed together briefly, the nature of their relationship is pure speculation. Some sources describe a contentious relationship, while others a friendly one. Our Flag Means Death unapologetically casts them as lovers. Concerning Bonnet’s real life, the show accurately depicts Bonnet leaving his aristocratic life behind to become a pirate. Some historians suggest that perhaps this was due to a mental break of some kind, which the show explores. It is also widely reported that Bonnet was not an instinctually good pirate when he first started, and the show has a lot of fun driving that point home. However, the show changes other details of Bonnet’s life, like who his family members were, for the sake of the narrative.

Both address the wider historical context in which these stories are set, albeit to varying degrees depending on the tone of their respective genres.

Differences in Tone

While both pirate stories display democracy aboard a pirate ship, the main difference between the two adaptations is that Our Flag Means Death doesn’t paint pirates as pioneers of democracy or connect this self-governance to our ideas about political freedom and participation today. But, as Under the Banner of King Death suggests, they in fact do deserve that credit. Part of this is due to the differences between the genres of the two works. As a comedy, Our Flag Means Death certainly mocks the British government and its institutions, which drove Bonnet to piracy, but its characters are almost too goofy to be seriously championed as political revolutionaries. They are shown to be egalitarian, but a point isn’t made of it as much as in Under the Banner of King Death, simply because the heart of the show’s story does not lie there.

Presumably for similar reasons, Our Flag Means Death glosses over some elements of Atlantic history that Under the Banner of King Death addresses, most notably the slave trade. Rediker, as a scholar of Atlantic history, was careful to demonstrate how pirates interacted with the slave trips and traders, who were actively voyaging at the same time as pirates were. Our Flag Means Death has a culturally and racially diverse cast, but there is little mention of how canonically each person ended up on the ship. While the racial hierarchy of the English is addressed—and then subverted by the crew—our protagonists never encounter a ship carrying enslaved people. Again, this is probably because it is a comedy. As a drama, Under the Banner of King Death is better equipped to address such a topic with the weight and nuance it deserves.

These stories act as a powerful critique of the social constraints that the characters break away from. By showcasing the beauty and civility pirates create in their lives on free vessels, these stories highlight the harshness and absurdity of the system that tried to deny them this freedom in the first place—all while claiming to be the more “civilized” way of living.

And, of course, both stories love a good pirate song.

About the Author

Gabel Strickland is a digital and social media intern at Beacon Press. She is getting her BS degree in journalism at Emerson College with a minor in publishing, comedy writing and performance.