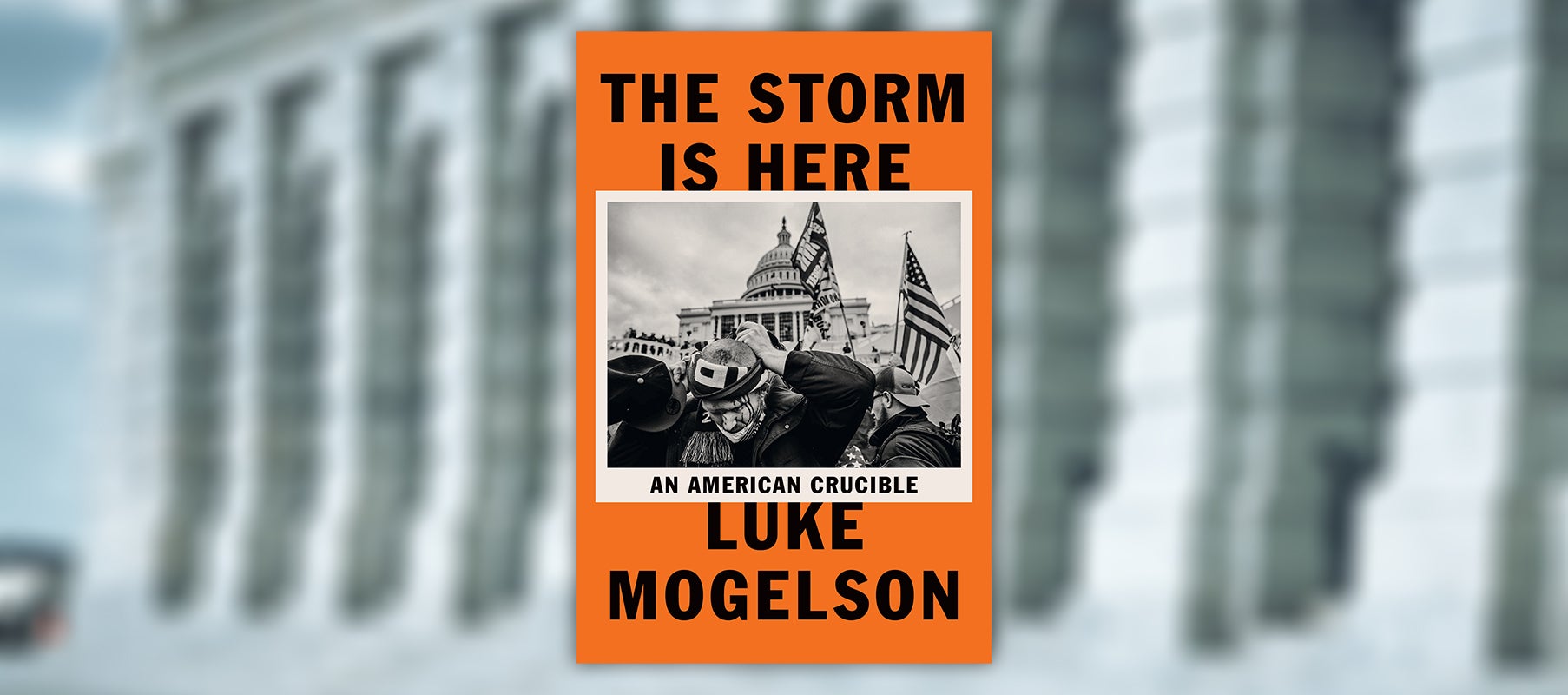

After years of living abroad and covering the Global War on Terrorism, Luke Mogelson went home in early 2020 to report on the social discord that the pandemic was bringing to the fore across the US. An assignment that began with right-wing militias in Michigan soon took him to an uprising for racial justice in Minneapolis, then to antifascist clashes in the streets of Portland, and ultimately to an attempted insurrection in Washington, D.C. His dispatches for The New Yorker revealed a larger story with ominous implications for America. They were only the beginning.

Chapter One

Let Us In

It started in Michigan. On April 15, 2020, thousands of vehicles convoyed to Lansing and clogged the streets surrounding the state capitol for a protest that had been advertised as “Operation Gridlock.” Drivers leaned on their horns, men with guns got out and walked. Signs warned of revolt. Someone waved an upside-down American flag. Already-nine months before January 6, seven months before the election, six weeks before a national uprising for police accountability and racial justice-there were a lot of them, and they were angry. Gretchen Whitmer, Michigan’s Democratic governor, had recently extended a stay-at-home order and imposed additional restrictions on commerce and recreation, obliging a long list of businesses to close. Around thirty thousand Michiganders had tested positive for COVID-19-the third-highest rate in the country, after New York and California-and almost two thousand had died. Most of the cases, however, were concentrated in Detroit, and the predominantly rural residents at Operation Gridlock resented the blanket lockdown. On April 30, with Whitmer holding firm as deaths continued to rise, they returned to Lansing.This time, more were armed and fewer stayed in their cars. Michigan is an open-carry state, and no law prohibited licensed owners from bringing loaded weapons inside the capitol. Men with assault rifles filled the rotunda and approached the barred doors of the legislature, squaring off against police. Others accessed the gallery that overlooked the Senate. Dayna Polehanki, a Democrat from southern Michigan, tweeted a picture of a heavyset man with a Mohawk and a long gun in a scabbard on his back. “Directly above me, men with rifles yelling at us,” she wrote.

The next day, a security guard in Flint turned away an unmasked customer from a Family Dollar. The customer returned with her husband, who shot the guard in the head. Later that week, a clerk in a Dollar Tree outside Detroit asked a man to don a mask. The man replied, “I’ll use this,” grabbed the clerk’s sleeve, and wiped his nose with it. By then, the movement that had begun with Operation Gridlock had spread to more than thirty states. In Kentucky, the governor was hanged in effigy outside the capitol; in North Carolina, a protester hauled a rocket launcher through downtown Raleigh; in California, a journalist covering an anti-lockdown demonstration was held at knifepoint; ahead of a rally in Salt Lake City, a man wrote on Facebook, “Bring your guns, the civil war starts Saturday . . . The time is now.”

I was living in Paris, where, since late March, we had been permitted to go outside for a maximum of one hour per day, and to stray no farther than a kilometer from our homes. Most businesses were closed (except those “essential to the life of the nation,” such as bakeries and wine and cigarette shops). Few complained. Every night at eight o’clock, we opened our windows and banged metal pots with wooden spoons to celebrate French medical workers; down the block from my apartment, a pharmacist stepped into the street and waved. I’d been a foreign correspondent for nearly a decade and during that time had not spent more than a few consecutive months in the US. The images of men in desert camo, flak jackets, and ammo vests, carrying military-style carbines through American cities, portrayed a country I no longer recognized. One viral photograph struck me as particularly exotic. It showed a man with a shaved head and a blond beard, mid-scream, his gaping mouth inches away from two officers gazing stonily past him, in the capitol in Lansing. What accounted for such exquisite rage? And why was it so widely shared?

In early May, I took an almost-empty flight to New York, then a slightly fuller one to Michigan.

My first stop was Owosso, a small town on the banks of the Shiawassee River, in the bucolic middle of the state. I arrived at Karl Manke’s barbershop a little before nine a.m. The neon Open sign was dark; a crowd loitered in the parking lot. Spring had not yet made it to Owosso, and people sat in their trucks with the heaters running. Some, dressed in fatigues and packing sidearms, belonged to the Michigan Home Guard, a civilian militia. A week before, Manke, who was seventy-seven, had reopened his business in defiance of Governor Whitmer’s prohibition on “personal care services.” That Friday, MichiganÕs attorney general, Dana Nessel, had declared the barbershop an imminent danger to public health and dispatched state troopers to serve Manke with a cease-and-desist order. Over the weekend, Home Guardsmen had warned that they would not allow Manke to be arrested. Now it was Monday, and the folks in the parking lot had come to see whether Manke would show up.

“He’s a national hero,” Michelle Gregoire, a twenty-nine-year-old school bus driver, mother of three, and Home Guard member, told me. She was five feet four but hard to miss. Wearing a light fleece jacket emblazoned with Donald Trump’s name, she waved a Gadsden flag at the passing traffic. Car after car honked in support. Michelle had driven ninety miles, from her house in Battle Creek, to stand with her comrades. She’d been at the capitol on April 30, and did not regret what happened there. When I mentioned that officials were considering banning guns inside the statehouse, she laughed: “If they go through with that, they’re not gonna like the next rally.”

Manke appeared at nine thirty, to cheers and applause. He had a white goatee and wore a blue satin smock, black-rimmed glasses, and a rubber bracelet with the words “When in Doubt, Pray.” He climbed the steps to the front door stiffly, his posture hunched. The previous week, he’d strained his back working fifteen-hour days, pausing only to snack on hard-boiled eggs brought to him on paper plates by his wife. When the Open sign flickered on, people crowded inside. Manke had been cutting hair in town for half a century and at his current location since the eighties. The phone was rotary, the clock analog. An out-of-service gumball machine stood beside a row of chairs. Black-and-white photographs of Owosso occupied cluttered shelves alongside old radios and bric-a-brac. Also on display were flashy paperback copies of the ten novels that Manke had written. Unintended Consequences featured an antiabortion activist who “stands on his convictions”; Gone to Pot offered readers “a daring view into the underbelly of the sixties and seventies.” As Manke fastened a cape around the first customer’s neck, a man in foul-weather gear picked out a book and deposited a wad of bills in a wicker basket on the counter. “My father was a barber,” he told Manke. “He believed in everything you believe in. Freedom. We’re the last holdout in the world.”

Manke nodded. “We did this in seventeen seventy-six, and we’re doing it again now.”

Like the redbrick buildings and decorative parapets of Owosso’s historic downtown, there was something out of time about him. During several days that I would spend at the barbershop, I’d hear Manke offer countless customers and journalists subtle variations of the same stump speech. He’d lived under fourteen presidents, survived the polio epidemic, and never witnessed such “government oppression.” Governor Whitmer was not his mother. He’d close his business when they dragged him out in handcuffs, or when he died, or when Jesus came-“whichever happens first.” He had a weakness for pat aphorisms, his delight in them undiminished by repetition. “I got one foot in the grave, the other on a banana peel”; “Politicians come to do good and end up doing well”; “You can’t fool me, I’m too ignorant.” Nearly every interview Manke gave concluded with a recitation of the serenity prayer, which he delivered with theatrical Žlan, as if oblivious to the possibility that anyone might have heard it before.

“You’re getting a scoop,” he assured me when I introduced myself. “American rebellion.”

Customers continued to arrive, and the phone did not stop ringing. Some people had traveled hundreds of miles. They left cards, bumper stickers, leaflets, brochures. A security contractor offered his services, free of charge. So did a scissors sharpener. (Manke: “You do corrugations?” Sharpener: “Of course. God bless you, and God bless America.”) A local TV crew squeezed into the shop, struggling to social-distance in the crush of waiting men, recording Manke with a boom mic as he sculpted yet another high-and-tight. Around noon, Glenn Beck called, live on the air. “It’s hardly my country anymore, in so many different ways,” Manke told him. “You remind me of my father,” Beck responded, with a wistful sigh.

Manke seemed to remind everybody of something or someone that no longer existed. Hence the people with guns outside, ready to do violence on those who threatened what he represented. You could not have engineered a more quintessential paragon of that mythical era when America was great.

One day at the barbershop, I was approached by a man clad from head to toe in hunting gear, missing several teeth. He hadnÕt realized I was press. Manke had first come to the attention of the attorney general, the man informed me, because of a reporter from Detroit. He held out his arms to indicate the woman’s girth.

“A big Black bitch.”

In the 1950s, when Manke was in high school, Owosso was a “sundown town”: African Americans were not welcome. Like much of rural Michigan, it remained almost exclusively white. Detroit, an hour and a half to the south, was 80 percent Black. Because politics broke down along similar lines-less-populated counties voted Republican; urban centers, Democrat-partisan rancor in the state could often look like racial animus. While conservatives tended to ridicule any such interpretation as liberal cant, the pandemic had created two new discrepancies that were hard to ignore. The first was that COVID-19 disproportionately affected Black communities, in Michigan as well as nationwide. The second was that the people mobilizing against containment measures were overwhelmingly white.

On April 30, the state representative Sarah Anthony had watched from her office across the street as anti-lockdown protesters filled the capitol lawn. Anthony had been born and raised in Lansing. In 2012, at the age of twenty-nine, she’d become the youngest Black woman in America to serve as a county commissioner. Six years later, a landslide victory made her the first Black woman to represent Lansing in the state legislature. As Anthony walked from her office to the capitol, she had to navigate a heavily armed white mob. She noticed a Confederate flag. A man waved a fishing rod with a naked Barbie doll-brunette, like Whitmer-dangling from a mini noose. Men screamed insults. A sign declared: TYRANTS GET THE ROPE.

Anthony was in the House of Representatives when the mob entered the building. “It just felt like, if they had come through that door, I would’ve been the first to go down,” she recalled.

We were in the rotunda, where she had insisted on giving me a tour. Her eyes brightened above her mask as she pointed out the star-speckled oculus in the apex of the dome 160 feet above us. “It’s designed to inspire,” Anthony explained. “There’s a sense of awe.” At seventeen, she had participated in an after-school internship program at the statehouse, “for nerdy kids who had too many credits and needed something productive to do.” After shadowing Mary Waters, a Black representative from Detroit, she had resolved to become a politician. “To see a woman that looked like me in a leadership position-I didn’t know we could do that,” she said. As we strolled in a circle beneath the dome, it was easy to imagine the dazzled intern, gazing up.

Anthony’s reverence for the building had made April 30 that much more unsettling. A sanctum had been violated-its meaning changed. The structure was an equally potent symbol for the people whose cries she’d heard on the other side of the door, however. On the eve of the rally, Michelle Gregoire, the school bus driver and Home Guard member, had visited the capitol. Wearing a neon safety vest scrawled with covid-1984, she and two friends filming on their phones had climbed a marble staircase to the gallery in the House of Representatives. A sergeant at arms informed them that the legislature was not in session, the chamber closed. “This is our house,” responded one of them, striding past him and sitting on a bench. The chief sergeant at arms, David Dickson, arrived and grabbed the woman by her arm, attempting to remove her.

“You are not allowed to touch me!” the woman howled.

Dickson turned his attention to Michelle. When she also resisted, he dragged her into the hallway, through a pair of swinging doors.

“Stay out,” he told her.

That night, the women posted their footage on Facebook, with the caption “We are living in NAZI Germany!!!” Many of the protesters at the capitol the next day had watched the clips, including the man with the shaved head and blond beard in the viral photograph. He was not accosting the two officers in the image, it turns out-he was shouting at Dickson, who stood behind them, outside the picture’s frame. “You gonna throw me around like you did that girl?” the man was shouting. Other protesters called Dickson and his colleagues “traitors” and “filthy rats.”

I left several messages for Dickson at his office, but he never called me back. Eventually, I returned to the capitol and found him standing guard outside the legislature. His hair was starting to gray, and beneath his blazer his collared shirt strained a little at the midriff. In 1974, Dickson had become the first Black deputy in Eaton County. He’d gone on to serve for twenty-five years as an officer in Lansing. After some polite conversation, I asked whether he thought that any of the visceral acrimony directed at him on April 30 might have been connected to his skin color and to that of the white women he’d ejected the day before.

Dickson frowned. “I don’t play the race card,” he said. Given his deprecating tone, I wondered if he’d been dodging my calls out of concern that I would raise this question. It was a question you could not really help raising in Michigan. To what extent was the exquisite rage behind the anti-lockdown fervor white rage? Dickson had no interest in discussing it. Of his encounter with Michelle, he told me, “I didn’t sleep for weeks. You don’t feel good about those kinds of things.” In his opinion, the white men who had threatened and belittled him had simply failed to grasp that he was duty bound to enforce the statehouse rules. “I love my job,” he stated with finality, putting an end to the interview.

For others, the answer to the question was self-evident. After April 30, Sarah Anthony acquired a bulletproof vest. Though she was anoptimist by nature, her outlook had dimmed. “People are angry about being unemployed, about having to close their businesses—I get that,”she said. “But there are elements, extremists, who are using this as anopportunity to ignite hate. Hate toward our governor, hate toward government,and also hate toward Black and brown people. These conditions are creating a perfect storm.”

CAMOUFLAGE

The April 30 protest had been organized by a few men on Facebook calling themselves the American Patriot Council. Two and a half weeks later, they held a second demonstration, in Grand Rapids, at a plaza known as Rosa Parks Circle. This time, there were no Confederate flags. A video from the Lansing rally, which had sparked backlash online,showed two adolescent girls dancing in rubber masks: one of Trump, the other of Obama with exaggeratedly dark skin. In Grand Rapids, the same two girls danced to “Bleed the Same,” by the gospel singer Mandisa. “Are you Black? Are you white?” Mandisa crooned.“Aren’t we all the same inside?”

The optics felt effortful, to say the least. I saw one person of colorin the crowd. On the periphery, dozens of armed white men in tacticalapparel surveilled the plaza. A few held flags with the Roman numeral III—a reference to the dubious contention that only 3 percent of colonists fought the British, and a generic emblem signifying readiness to do the same against the US government. (Americans who displayed the symbol and embraced the mentality that it represented often identifiedas “Three Percenters.”) Some were Home Guard. Others belongedto the Michigan Liberty Militia, including the heavyset manwith the Mohawk whose picture Dayna Polehanki had tweeted fromthe Senate floor. He wore a sleeveless shirt and a black vest laden with ammunition. A laminated badge read security. His habit of pressinga small gadget embedded in his ear with his index and middle fingers felt like an imitation of something he had seen on-screen. He appeared to be having an excellent time.

A general atmosphere of cheerful make-believe was accentuated by the presence and intense engagement of actual children. One of them, materializing suddenly, interrupted my conversation with a Home Guardsman: “Excuse me, what kinds of guns are those?”

We looked down to find a ten-year-old boy with a businesslike expression.

“This is an AK-47,” the Home Guardsman told him.

“With a flashlight or a suppressor?”

“That’s a suppressor. This is a flashlight with a green dot.”

“What pistol is that?”

“That is a Glock. A nine-millimeter.”

The boy seemed underwhelmed. “I’ve heard a lot of people say that,” he said.

“Before you ever pick up a gun, you have to have your hundred hours of safety classes, right?” admonished the Home Guardsman, bristling a little.

“I already have them.”

The keynote speaker was Dar Leaf, a sheriff from nearby Barry County who had refused to enforce Governor Whitmer’s executive orders. Diminutive, plump, and bespectacled, with a startling falsetto and an unruly mop of bright yellow hair, Leaf cut an unlikely figurein his uniform, the baggy brown trousers of which bunched around his ankles. Nevertheless, he promptly captivated his audience by invitingit to imagine an alternate version of the past—one in which Alabama officers, upholding the Constitution, had not arrested Rosa Parks.

To facilitate the thought experiment, Leaf channeled a hypothetical deputy boarding the bus on which Parks—in the real world—was detained. “Hey, Ms. Parks,” said the sheriff, playing the part. “I’m gonna make sure nobody bothers you, and you can sit wherever you want.”

The crowd cheered.“Thank you!” a white man cried out.

In Alabama, during the sixties, sheriffs and deputies were often more ruthless than their municipal counterparts toward Black citizens. The sheriff Jim Clark led a horseback assault against peaceful marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, in Selma, and habitually terrorizedAfrican Americans with a cattle prod that he wore on his belt. Dar Leaf, though, saw himself as heir to a different legacy. Accordingto him, the weaponization of law enforcement to suppress Black activism arose from the same infidelity to American principles of individual freedom that in our time defined the political left. “I got news for you,” Leaf said. “Rosa Parks was a rebel.” And then, for those minds not yet wrapped around what he was telling them: “Owosso has their little version Rosa Parks, don’t they? Karl Manke!”

The equivalence was all the more incredible given that Leaf belonged to the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association, or CSPOA. The notion of the “constitutional sheriff” had been first promulgated by William Potter Gale, a Christian Identity minister from California. Christian Identity theology held that Europeans were the true descendants of the lost tribes of Israel; that Jews were the diabolicprogeny of Eve and the serpent; and that all non-whites were subhuman “mud people.” In the seventies, Gale developed a movement of rural resistance to federal authority that expanded the model of white vigilantism in the South to a national scale, adding to the fear of Black integration the specter of governmental infiltration by Communistsand Jews. He called his organization Posse Comitatus, which is Latinfor “power of the county,” and it recognized elected sheriffs as “the only legal law enforcement” in America. Posse Comitatus groups across the country were instructed to convene “Christian common law grand juries,” indict public officials who violated the Constitution,and “hang them by the neck.” Gale’s guidance on what offenses merited such punishment was straightforward: any enforcement of federal tax regulations or of the Civil Rights Act.

The CSPOA argued that county sheriffs retained supreme authority within their jurisdictions to interpret the law, and that their primary responsibility was to defend their constituents from state and federal overreach. In Grand Rapids, Sheriff Dar Leaf told the anti-lockdowners, “We’re looking at common-law grand juries. I’d like to see some indictments come out of that.” At the end of his speech, he called the Michigan Liberty Militia onto the stage. “This is our last home defense right here,” he said. Glancing at the heavyset man with the Mohawk, Leaf added, “These guys have better equipment than I do. I’m lucky they got my back.”

NAZI TIMES

Later, while reviewing my videos from Rosa Parks Circle, I noticed a woman with a toothbrush mustache painted on her upper lip. Looking closer, I saw that she also wore a wig. It was brunette and wavy, intended to resemble Governor Whitmer’s hair. The woman wasn’t doing Hitler, in other words: she was doing Whitmer doing Hitler. She would probably have said that she was doing “Whitler.”

While comparing pandemic measures to the atrocities of the Third Reich might have constituted its own kind of antisemitism, it also suggested how desperate many anti-lockdowners understood the situation to be. Nazis were a frequent topic of conversation in the barbershop— which, for Karl Manke’s supporters, represented a bulwark against the kind of creeping authoritarianism that had gradually engulfed Germany in the 1930s. Manke himself had a lot to say on the subject. His great-grandfather had immigrated from Germany, and Manke had grown up attending a Lutheran church with services in German. He often cited the Jewish victims of the Holocaust as a cautionary tale. “They would trade their liberty for security,” he told a customer one afternoon. “Because the Nazis said to them, ‘Get in these cattle cars, and we’re gonna take you to a nice, safe place. Just get in.’”

“I would rather die than have the government tell me what to do,” the man in the chair responded.

In mid-May, when Attorney General Nessel suspended his business license, Manke exclaimed, “It’s tyrannical! I’m not getting in the cattle car!” His 2015 novel, Age of Shame, recounts the travails of Rhena Nowak, a thirteen-year-old Polish Jew who is raped by a German sergeant and loaded into a cattle car during the Second World War. “Millions of Jews have already been moved through this process with little to no resistance,” Manke writes, “holding true to their centuries-old compliance to their weakness toward fatalism.” Just a few outliers “are not cut out to become willing participants in this collapse of strength.” Rhena pries loose the slats nailed over a window and leaps from the train, earning her freedom. When I bought a copy of Age of Shame, Manke inscribed the title page with one of his timeworn maxims: “History unheeded is history repeated.”

A few days later, a customer in striped knee-length shorts caught my eye. While in line, he’d become intensely absorbed in a thick hard- cover book—the seminal evangelical treatise How Should We Then Live? When it was his turn, he told Manke that he was from Hamburg and they proceeded to talk in German. After the man paid, I followed him out and asked what they’d discussed. “We were just talking about how it was back in the Nazi times,” he said.

A meme shared widely at the beginning of the pandemic had juxtaposed a picture of American police enforcing social-distancing restrictions with an image of gestapo officers interrogating Jews in a European ghetto. At the time, I’d assumed that it was deliberate hyperbole, meant to provoke. But the longer I stayed in Michigan, the clearer it became that many anti-lockdowners sincerely placed mask mandates and concentration camps on the same continuum. “This has nothing to do with the virus,” a sixty-eight-year-old retiree told me outside the barbershop. “They want to take power away from the people, and they want to control us. We’re never gonna get our freedoms back from this if we don’t stop it now.” Given the stakes, violence was inevitable. “We’re a trigger pull away,” he said. “You’re gonna see it. We’re getting to the point where people have had enough.”

We had to raise our voices to hear each other over a Christian family loudly singing hymns. But I had the sense that the retiree would have been yelling anyway. “You got storm troopers coming in here!” he shouted, referencing the officers who’d served Manke with a cease- and-desist order. “They weren’t cops, they were storm troopers! They deserve to wear the Nazi emblem on their sleeves.”

When I went back inside, the phone was ringing. An anonymous caller wanted Manke to know that the National Guard was on its way. “We need more people,” a customer in a pressed shirt announced. I’d met him earlier. A self-described “citizen scientist,” he’d given me a flier explaining that masks prevented the body from detoxifying and therefore did more harm than good. “If we get more people, we can stand them off,” he told Manke.

“I would hope it’s a rumor,” Manke said.

“Whatever it is, we could use more people.”

“Well, if they come with a tank . . .”

“Like Tiananmen Square!” the citizen scientist agreed. He lapsed into pensive silence, as if calculating how many people it would take to stand off a tank. Finally, a solution occurred to him: “The sheriff can stop them. The sheriff has the power to stop the National Guard, the federal government, everybody.”

Someone looked up the number. Reaching a voice mail, the citizen scientist left a message: “Attention, Sheriff. We need you over here at the barbershop. Please come here immediately to attend to a situation. We need your help here to defend our constitutional rights. Please hurry up.”

After a while, it became apparent that neither the sheriff nor the National Guard was coming. I went back outside. The family had stopped singing and was now reciting scripture. Psalm 2: “Why do the nations conspire and the peoples plot in vain?” The patriarch was joined by his son, daughter, and one-year-old grandson. “If there’s children, they won’t shoot tear gas,” he said. “That’s my hope, anyway—if we’re here, they back off.”

“Who backs off?” I asked.

“The Nazis.”

Copyright © 2022 by Luke Mogelson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

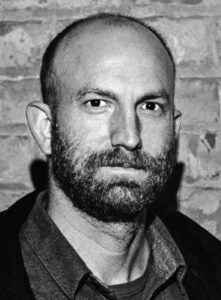

Luke Mogelson has written for The New Yorker since 2013, covering the wars in Afghanistan, Syria, Ukraine, and Iraq. During the pandemic, he reported from across the US. Previously, Mogelson was a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine, based in Kabul. He has won two National Magazine Awards and two George Polk Awards.

Luke Mogelson has written for The New Yorker since 2013, covering the wars in Afghanistan, Syria, Ukraine, and Iraq. During the pandemic, he reported from across the US. Previously, Mogelson was a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine, based in Kabul. He has won two National Magazine Awards and two George Polk Awards.