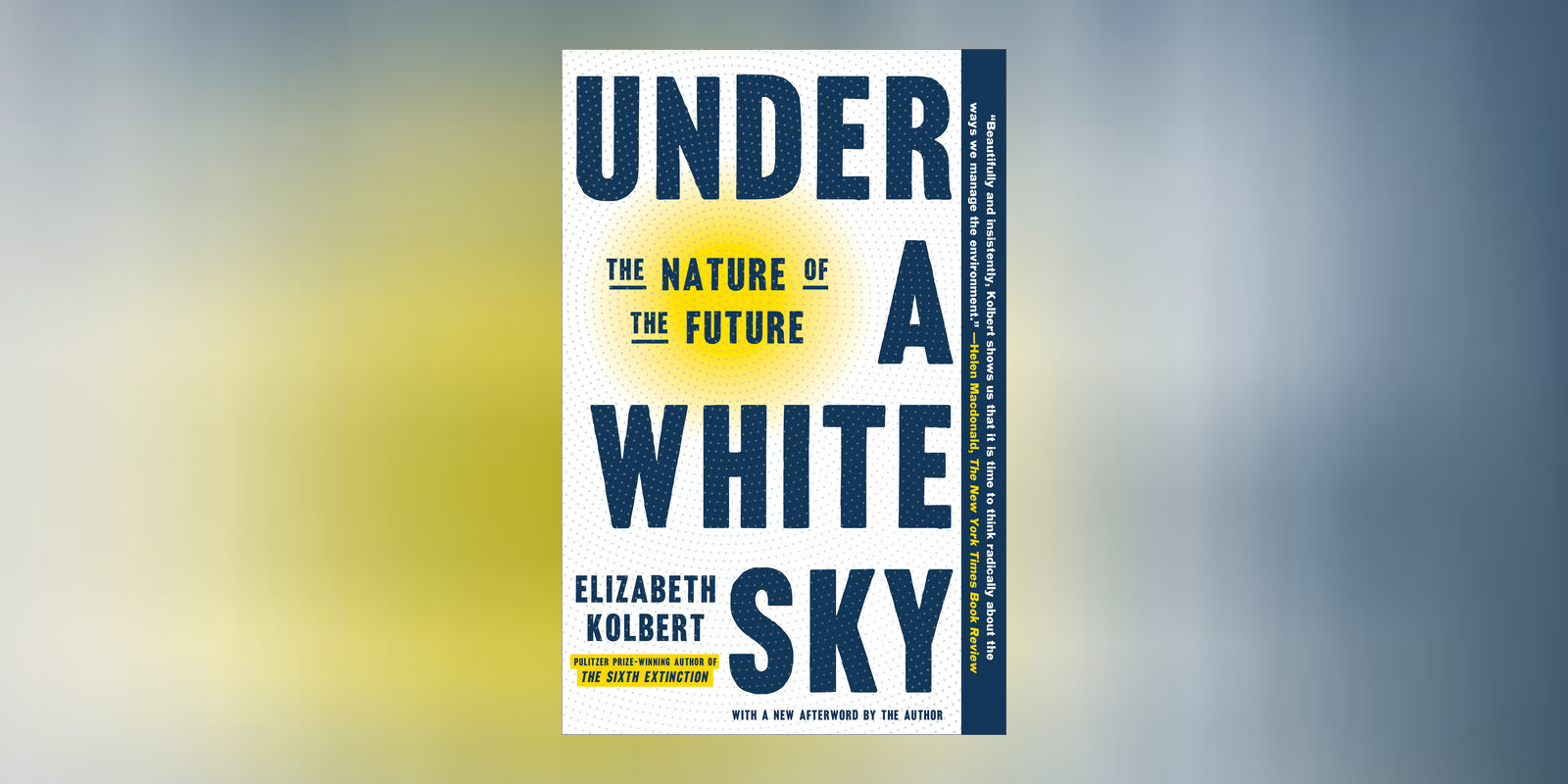

Contributed by Elizabeth Kolbert, author of Under a White Sky: The Nature of the Future

“I’m a realist,” Ruth Gates was saying. “I cannot continue to hope that our planet is not going to change radically. It already is changed.”

Gates, then the head of Hawaii’s Institute of Marine Biology, had taken me out to the back of the institute to visit a set of giant outdoor tanks. In each one, corals were being raised under conditions of carefully-calibrated stress. The idea behind the experiment was to identify colonies that could survive in a changing ocean. Gates’s hope was that these “super-corals” could then be transferred back to the sea to seed the reefs of the future.

“Our project is acknowledging that a future is coming where nature is no longer fully natural,” she told me.

It’s often said that we have entered a new epoch, the Anthropocene, defined by human impacts on the planet. Global warming, industrial agriculture, plastic pollution, radioactive fallout—all of these human activities have altered the globe on a geological scale. The planet, as Gates observed, “already is changed,” and many people, along with countless other species, are already suffering as a result. What do we do now?

It’s no exaggeration to say that this is the defining question of our time. Of course, there’s no simple answer to it. And this is precisely why I wrote Under a White Sky. In the book, I try to present the information that students—indeed, all citizens—need to consider. But in contrast to most books on weighty topics, I try to do so in a way that’s fun—even, I hope, funny. In the end, I leave readers to decide how to respond. The book is not a polemic so much as a provocation. It’s meant to spur discussions that challenge beliefs all along the political spectrum, and it was written very much with students in mind. They, after all, will be called upon to make the decisions that will decide “the nature of the future.”

Consider gene editing. Gene editing has, in recent years, become much easier and less expensive, and this has opened up vast new opportunities for tinkering with nature. Many Americans are deeply, viscerally opposed to this form of manipulation. But what if gene editing could save a species? In the early 20th century, a fungal disease imported from Asia swept through North America. It killed off virtually every American chestnut on the continent—some four billion trees. Now, William Powell, a professor at the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry, has developed a genetically-modified chestnut tree that can fend off the blight. The tree contains a single gene imported from wheat. “I always say that it’s 99.9997-per-cent American chestnut,” Powell told me when I went to visit him in his lab in Syracuse. If the choice is between a tree that’s “99.9997-per-cent American chestnut” and no chestnut trees at all, what’s the right call?

Or consider solar geoengineering. The idea of solar geoengineering comes from volcanic eruptions, which, when they’re big enough, shoot droplets of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere. These reflective droplets bounce sunlight back toward space, producing temporary global cooling. If humans decided to mimic volcanoes by spreading some sort of reflective material in the stratosphere, we could, in theory at least, counteract the effects of global warming. Most people (myself included) react to the notion of purposely dimming the sun with horror. But what if it could reduce human suffering, or prevent entire ecosystems, like coral reefs, from collapsing? “We live in a world where deliberately dimming the f***ing sun might be less risky than not doing it,” is how Andy Parker, director of the Solar Radiation Management Governance Initiative, has put it.

Under a White Sky can engage students in thinking about complex questions that have no clear solutions. And, for better or worse, those are the questions that they—and the world—will be grappling with.