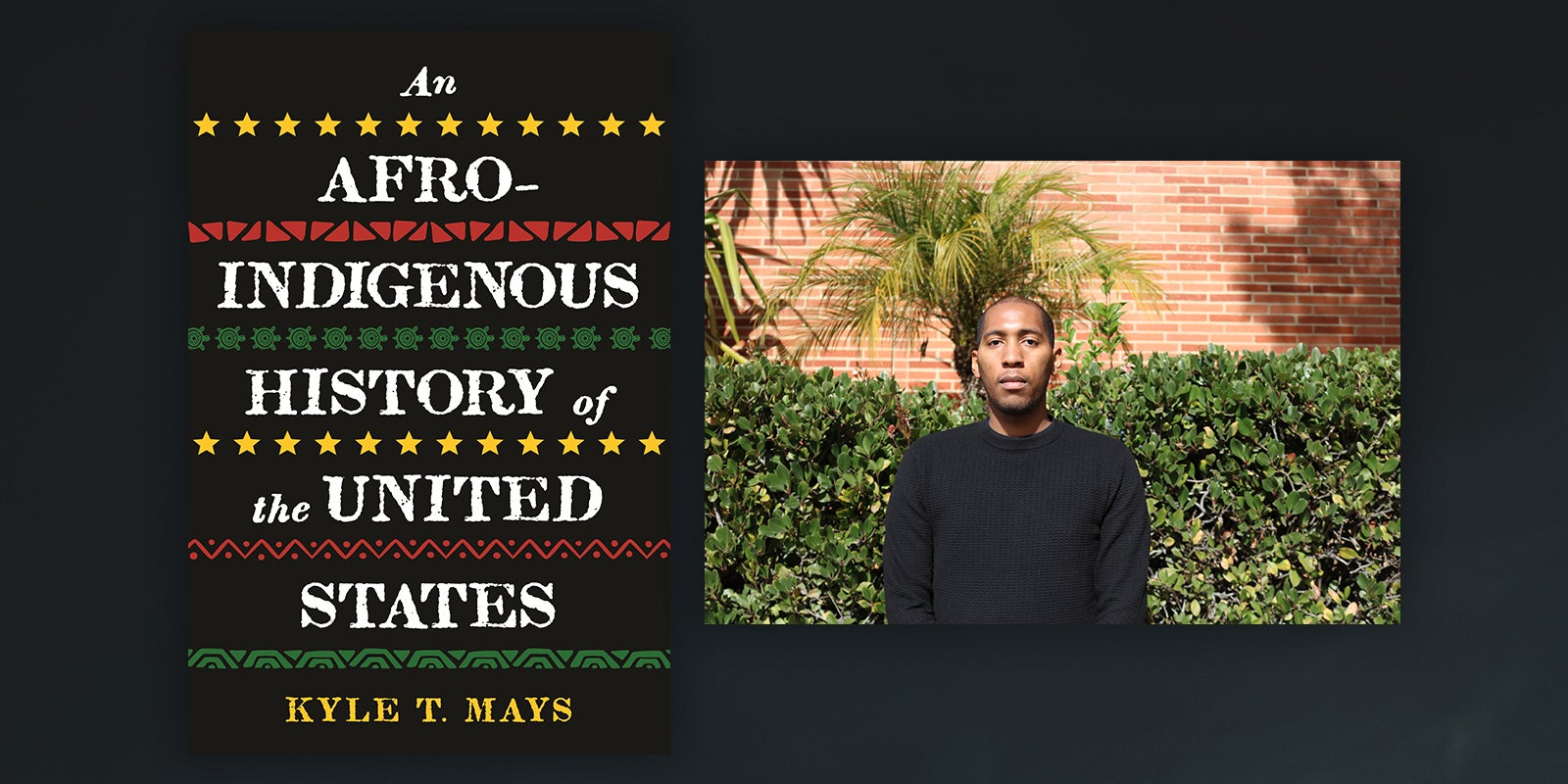

Beginning with pre-Revolutionary America and moving into the movement for Black lives and contemporary Indigenous activism, Afro-Indigenous historian, Kyle T. Mays argues that the foundations of the US are rooted in antiblackness and settler colonialism, and that these parallel oppressions continue into the present. He explores how Black and Indigenous peoples have always resisted and struggled for freedom, sometimes together, and sometimes apart. Whether to end African enslavement and Indigenous removal or eradicate capitalism and colonialism, Mays show how the fervor of Black and Indigenous peoples calls for justice have consistently sought to uproot white supremacy.

Mays uses a wide-array of historical activists and pop culture icons, “sacred” texts, and foundational texts like the Declaration of Independence and Democracy in America. He covers the civil rights movement and freedom struggles of the 1960s and 1970s, and explores current debates around the use of Native American imagery and the cultural appropriation of Black culture. Mays compels us to rethink both our history as well as contemporary debates and to imagine the powerful possibilities of Afro-Indigenous solidarity.

I am writing this book for at least three reasons. First, because of my personal identity: I am Black and Saginaw Chippewa. Second, if I am to imagine a new world, one that brings an end to a world that hates Black people and reproduces antiblackness and white supremacy, and a world that erases Indigenous people and reproduces their dispossession through settler colonialism, I intend to tell some histories that have been ignored at best or made invisible at worst. Third,

there is a deeply intellectual component rooted in my interactions in graduate school.When I visited a prospective graduate school, I met with an infamous Black studies professor in his office. When I told him that I was interested in doing research on the links between the American Indian Movement and the Black Panther Party, he scoffed, saying, “There’s no relationship.” Beyond the fact that he was at worst lying and at best very misinformed—I believe he knew of some of these histories but, because of his “hotepness”—he didn’t want to discuss the importance of Black and Indigenous solidarity. (By “hotep,” I mean the hypermasculine Black male who has an ahistorical, Afrocentric conception of himself; refers to men and women as “kings” and “queens”; and basks in their alleged connection to ancient Africa and all of its glory.) He had no basis for that claim. I was also upset that he so easily dismissed my research idea. However, since that time, I’ve learned that Black and Indigenous people continue to produce similar responses as that Black studies professor. As an Afro-Indigenous person, I also know that there is a crucial need for a book that considers the history of Afro-Indigenous struggles, their interactions throughout US history, and how that particular relationship is the foundation for our new sphere of freedom. For me, it is essential that I include Black and Indigenous people in our collective understanding of liberation. I want to recover some lost histories to show that Black and Indigenous peoples’ histories are tied not only to enslavement and dispossession but also a struggle for justice. The journey has entailed many diverse challenges, all while Black and Indigenous peoples have sought belonging and freedom in a country that continues to say, “We don’t want you.”

How does one begin to write a large book on the topic of intersecting Black American and Native American cultures, histories, and peoples? As a Black and Saginaw Anishinaabe person from Michigan, I begin with my story. My mom is Black American and was raised in Cleveland, Ohio; she is a descendant of enslaved people from South Carolina on her father’s side. Her grandmother came to Cleveland, Ohio, in the mid-1930s from Fayetteville, Georgia. My dad is Black and Saginaw Anishinaabe, and raised in Detroit and Lansing, Michigan. His grandmother, my great-grandmother, Esther Shawboose Mays, came to Detroit in the spring of 1940 from the Saginaw Chippewa reservation. She married a Black American man, Robert Isiah Mays, and his family was from Tennessee. They produced nine Afro-Indigenous children. Her children were very active in both Detroit’s Black and Indigenous community struggles from the 1960s through 1990s. This activism culminated in my aunt Judy Mays founding the Medicine Bear American Indian Academy—a Detroit Public School with an all–Native American curriculum, designed for Black and Indigenous as well as Latinx students. Medicine Bear was the third public school in the US to have been created with a Native American curriculum. Importantly, the school would not have been created without the advocacy of Black politicians in Detroit.

I come from two different communities. However, I would be remiss not to acknowledge that my Black ancestors came from Indigenous peoples. I don’t know the particular tribe; that information was lost because of slavery. I know about the Indigenous heritage of only part of myself. While it might be impossible to find out my personal African Indigenous heritage, I can at least acknowledge the larger history of Indigenous Africans, my heritage.

A major focus of this book is not only to analyze Black American and Indigenous relationships but also to recover and acknowledge the Indigenous roots of people of African descent. I am not claiming that those people are indigenous to what is now the United States, nor do I think Black folks should be so invested in what would be the equivalent of a white nationalist project such as the United States. We should be more visionary than that. However, US Indigenous peoples should also help think through the antiblackness that exists in their community and how they might, as Canadian Indigenous (Mississauga Nishnaabeg) writer and musician Leanne Betasamosake Simpson suggests, make room for Indigenous people on their land.

When I have traveled the country to discuss my research, I often get two versions of a comment or question about identity. First, a person of Black American ancestry might share that they have Cherokee blood in them, maybe Blackfeet. Or, someone, usually a young person, will ask me how I deal with being both Black and Indigenous. I tell them that, for me, it wasn’t a contradiction being Black and Indigenous. While others questioned me, my family didn’t question or

police my identity.I did experience an instance of being questioned by others—or identity policing—when I was a graduate student, attending an academic conference. I was at the hotel lobby, recognized a peer from my own graduate institution, and saw that they were with a group of other Native people. I’m sure I gave everyone some dap (exchanged a fist pound greeting), and then one of the people, from a Southwestern US tribal nation, asked, “Why are you wearing those earrings?” I replied, “‘Cause I like them.” They responded, “Where did you get them?” “From a powwow,” I snapped back, after quickly concluding that they wondered why a Black person had adorned themselves with “Native” earrings. This antiblack exchange made me angry, if not insecure.

Still, I never felt comfortable in my intellectual knowledge of Black and Indigenous relations until graduate school, because it was there that I was able to delve into the research and really read. I carved out time to think about my identity and how I wanted to help change the intellectual game of how we approach Afro-Indigenous history. Graduate school offered me five years to reflect on myself and learn how to be me—my full Afro-Indigenous self.

My quest in this book is to recover histories, reorient our understanding of historical events and peoples, and project what a present and future idea of Black and Indigenous solidarity might look like. We need a new way of talkin’ about these relationships.

In documenting encounters between Black and Indigenous peoples, I have focused the majority of my examples in this book in unexpected ways and places. In fact, the whole book could be considered unexpected. On the one hand, I challenge the very notion of what we “know” about these relationships. I am only mildly interested in writing about the relationship between, for example, the Five Tribes and enslaved Africans, though I’m sure that’s what many will expect. The topic of enslavement and dispossession in the nineteenth century dominates the books on African Americans and Native Americans. However, if we are to build a shared Afro-Indigenous future on stolen Indigenous land and recover the Indigenous roots of the ancestors of stolen Indigenous Africans, then it will require we find underexplored histories, rethink “accepted” histories, and survey solidarities and tensions—and also imagine how the world might look after white supremacy and settler colonialism have been dismantled.

I have not written this book as a historical narrative, where the author’s voice is almost entirely mute. Throughout the pages I offer commentary here and there so that you, dear reader, and I can have an in-text conversation.

Kyle T. Mays is an Afro-Indigenous (Saginaw Chippewa) writer and scholar of U.S. history, urban studies, race relations, and contemporary popular culture. He is an Assistant Professor of African American Studies, American Indian Studies, and History at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is the author of Hip Hop Beats, Indigenous Rhymes: Modernity and Hip Hop in Indigenous North America.