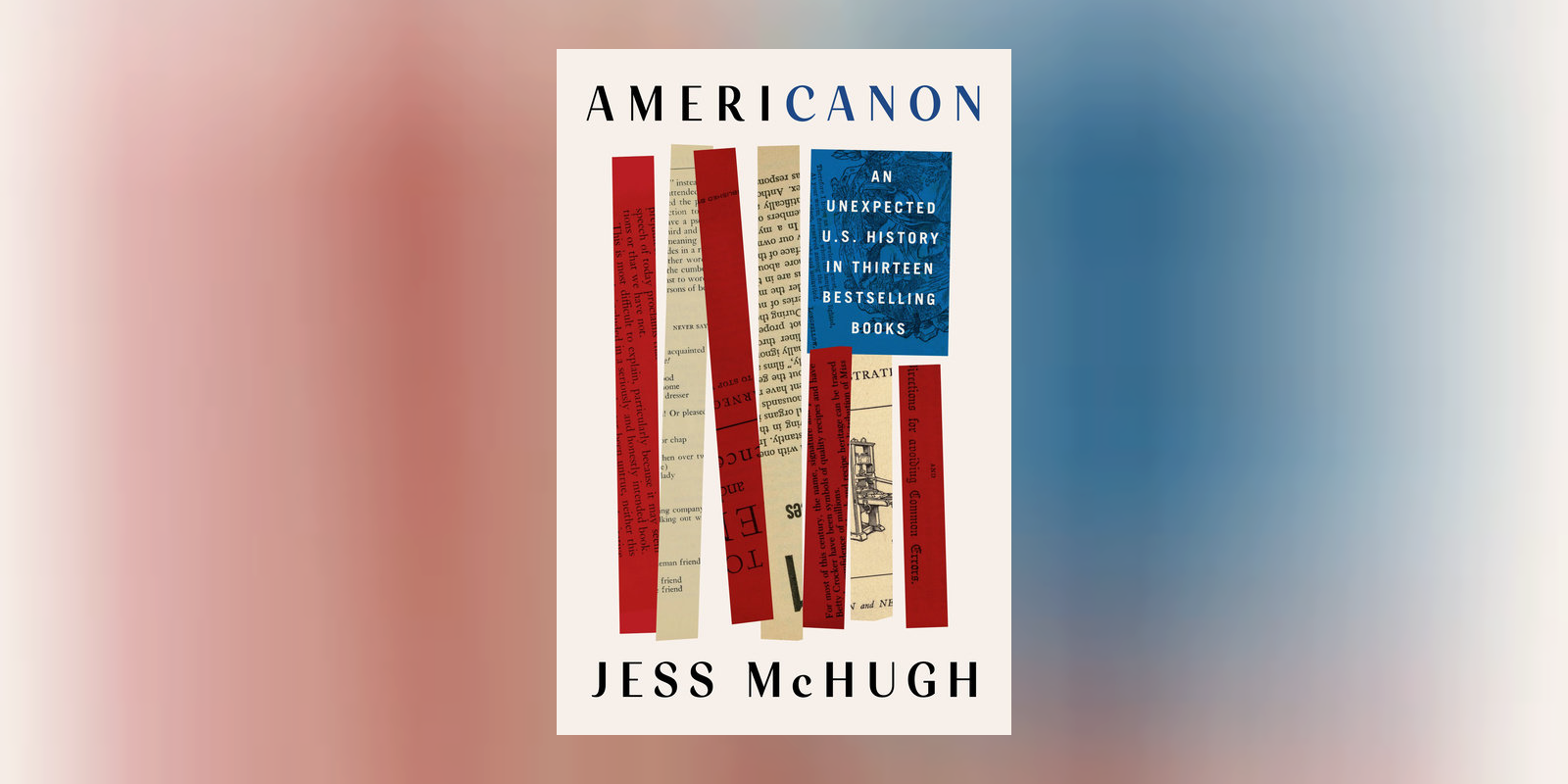

By: Jess McHugh

Who gets to tell the American story?

That was the question that preoccupied me in the years of researching and writing Americanon. I was fascinated by the ways in which commonplace books, owned by millions of Americans—from almanacs to primers to cookbooks—shaped and reshaped American identity over generations of reading.

Americanon begins with one of the best-known definers of American culture: dictionary author Noah Webster. As he sits in his study in the early nineteenth century attempting to write the dictionary, he’s plagued by distractions and doubt: His seven children running through the house interrupt his work; his frequent money troubles hang over his head—and the critics who ridiculed his plan to create an American language haunt his efforts.

In writing a dictionary that many Americans now refer to as simply the dictionary, he sought to give them a blueprint for a shared culture. In changing spellings to Americanize them (a word Webster coined), adding patriotic definitions for words such as “senate” or “president,” and in exalting the work of American writers, he looked to rally Americans around a new-found identity. It was a linguistic Declaration of Independence. He hoped American English would not only be as different from British English as Swedish or Dutch was from German—it would be better. Webster’s dictionary would succeed in becoming one of the perennial bestsellers in U.S. history, defining much more than words for generations of Americans.

My fascination with bestselling didactic books began with Noah Webster—and more specifically with a throwaway comment about him during an American history lecture. That sent me on the path to write a piece for the Paris Review about the nationalist roots of Webster’s dictionary, and from there I was engrossed by the lives of the books on our shelves we so rarely notice (and the often-fanatical authors who wrote them). I came to believe that the actual origins of our culture are more disparate than our founding documents, coming not only from presidents and revolutionaries but also from nationalist schoolteachers like Webster, or frontier boys such as William Holmes McGuffey.

From Noah Webster, this interest grew into a vast research project exploring how bestselling how-to manuals have shaped American identity. I spent years combing through sales data, interviewing close to 100 historians in various fields from American Studies to the History of Publishing, and of course spending hours upon hours with the primary texts themselves. In 2019, I was able to undertake a nine-city road trip to far-flung archives, immersing myself in the material, from the Betty Crocker archive (the bestselling cookbook in American history), to the offices of The Old Farmer’s Almanac, to the Dale Carnegie Institute (How to Win Friends and Influence People remains one of the bestselling business books some 70 years after its publication).

Americanon spans the full length of American history, and it touches on the history, literature, and culture of the American story and its many iterations from the Revolutionary period to now. This book is an exploration of how our story is written—through acts, through words, through mythology and self-promotion. It traces the origins of some of the nation’s most closely-held beliefs—meritocracy, optimism, exceptionalism—through the books that average Americans used every day. At the same time, Americanon looks at the ways in which exclusion has been baked into many of these values from the very start. American identity has long constructed itself through an amnesia about its most definitive and ugliest moments. The stories we tell so frequently about meritocracy, self-reliance, and equality must ignore centuries of slavery, genocide against indigenous peoples, and the free labor of women.

I hope this book will challenge students in particular to think about our culture in a new way: to conceive of American beliefs not as a natural evolution of “right” and “wrong” ideas but as a path from author to text to culture. We think the basis of our identity comes from the Constitution or from some generally agreed upon values, but random, often extreme people were also a big part of writing our national story. Moments of upheaval and unpredictable chaos, too, have shaped and reshaped our understanding of ourselves as Americans.

Especially for students, some of the characters in the book—Benjamin Franklin, Noah Webster, the Beecher family—might be familiar names. I hope that Americanon can bring them alive anew: nuancing them and connecting them to our canon and identity in a fresh way. Pulitzer-prize winner Jake Halpern described this book as “meticulously-researched and eminently readable,” and I think that’s what would make it a good fit in the classroom. Americanon is steeped in research, but it’s also approachable, encouraging the reader to delve into the quirks, biases, and downright strangeness of the characters throughout American history.

Finally, I hope Americanon can be a small part of the ongoing and necessary reckoning over the ways in which American identity has often been flattened or restricted, casting aside the diversity in region, ethnicity, and country of origin that we might rather embrace. The umbrella category of “American” doesn’t cease to exist when it expands, but it comes to incorporate a richer tapestry of the American experience.

Jess McHugh is a writer and researcher whose work has appeared across a variety of national and international publications, including The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, The Nation, TIME, The Paris Review, The Guardian, The New Republic, New York Magazine‘s The Cut, Fortune, Village Voice, The Believer, and Lapham’s Quarterly, among others. She has reported stories from four continents on a range of cultural and historical topics, from present-day Liverpool punks to the history of 1960s activists in Greenwich Village.