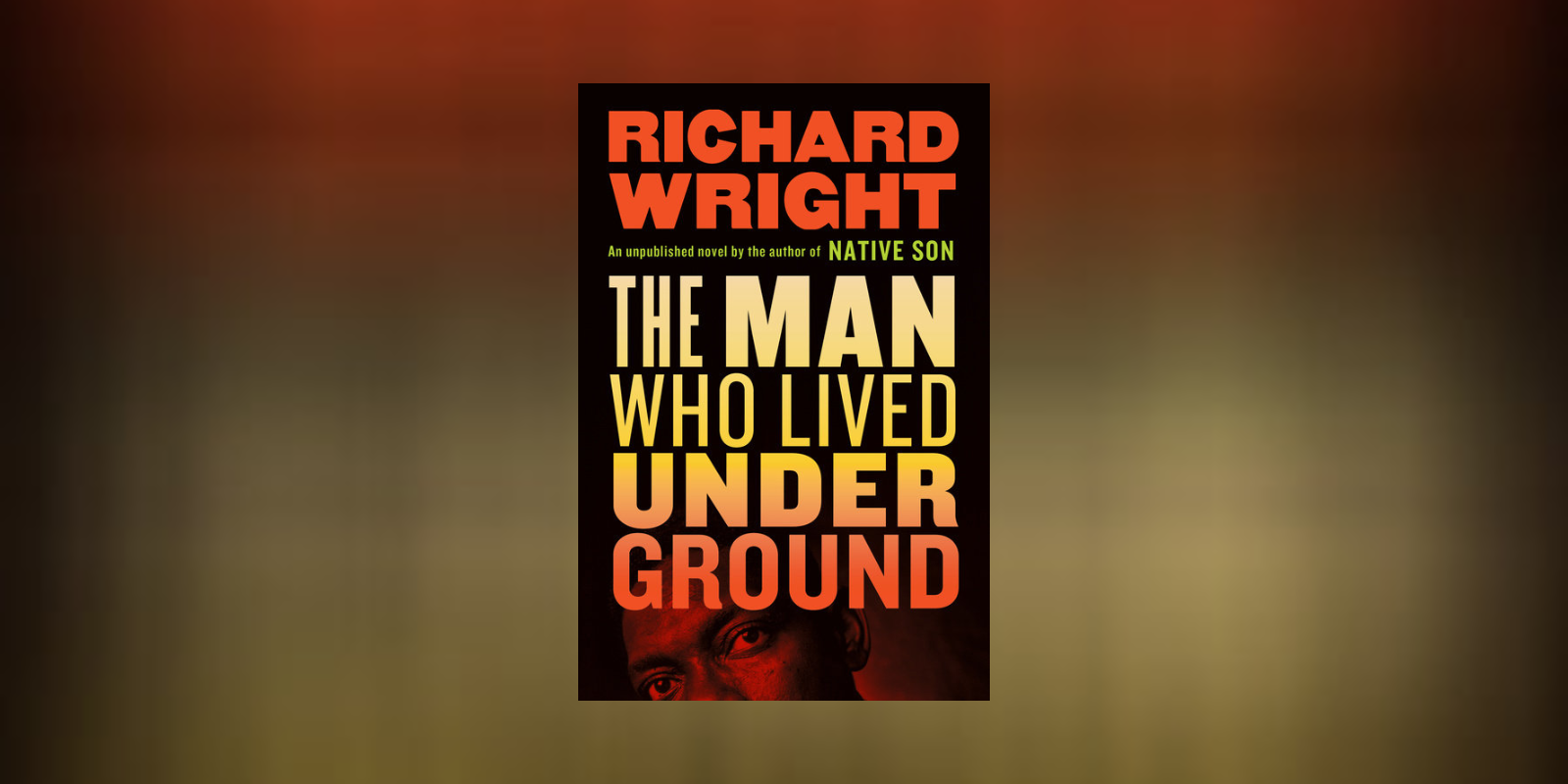

Richard Wright (1908–1960) is one of the most influential African American writers of the last century. But in the 1940s, at the height of his creative powers, he was unable to secure publication of perhaps his most important novel.

Now, for the first time, by special arrangement with the author’s estate, Library of America is publishing the full text of this incendiary novel about race and violence in America, the work that meant more to Wright than any other (“I have never written anything in my life that stemmed more from sheer inspiration”), in the form that he intended, complete with his companion essay, “Memories of My Grandmother.” Malcolm Wright, the author’s grandson, contributes an afterword.

In The Man Who Lived Underground, Fred Daniels, a Black man, is picked up by the police after a brutal double murder and tortured until he confesses to a crime he did not commit. After signing a confession, he escapes from custody and flees into the city’s sewer system.

This is the devastating premise of this scorching novel, a masterpiece that Richard Wright was unable to publish in his lifetime. Written between his landmark books Native Son (1940) and Black Boy (1945), it would eventually see publication only in drastically condensed and truncated form in the posthumous collection Eight Men (1961).

Kiese Laymon has called The Man Who Lived Underground “Wright’s most brilliantly crafted, and ominously foretelling, book.”

Richard Wright sitting on a sofa, Lido, Venice, 1950. (Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche/Getty Images)

The door of the police car swung open quickly and the man behind the steering wheel stepped out; immediately, as though following in a prearranged signal, the other two policemen stepped out and the three of them advanced and confronted him. They patted his clothing from his head to his feet.

“He’s clean, Lawson,” one of the policemen said to the one who had driven the car.

“What’s your name?” asked the policeman who had been called Lawson.

“Fred Daniels, sir.”

“Ever been in trouble before, boy?” Lawson said.

“No, sir.”

“Where you think you’re going now?”

“I’m going home.”

“Where you live?”

“On East Canal, sir.”

“Who you live with?”

“My wife.”

Lawson turned to the policeman who stood at his right. “We’d better drag ‘im in, Johnson.”

“But, mister!” he protested in a high whine. “I ain’t done nothing…”

“All right, now,” Lawson said. “Don’t get excited.”

“My wife’s having a baby…”

“They all say that. Come on,” said the red-headed man who had been called Johnson.

A spasm of outrage surged in him and he snatched backward, hurling himself away from them. Their fingers tightened about his wrists, biting into his flesh; they pushed him toward the car.

“Want to get tough, hunh?”

“No, sir,” he said quickly.

“Then get in the car, goddammit!”

He stepped into the car and they shoved him into the seat; two of the policemen sat at either side of him and hooked their arms in his. Lawson got behind the steering wheel. But, strangely, the car did not start. He waited, alert but ready to obey.

“Well, boy,” Lawson began in a slow, almost friendly tone, “looks like you’re in for it, hunh?”

© Julia Wright and Rachel Wright. Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.