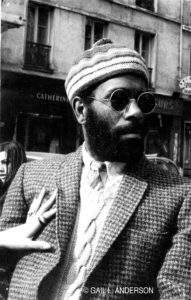

Associate Professor of English at Vanderbilt University Anthony Reed remembers William Melvin Kelley.

William Melvin Kelley is often described as a “lost” or “forgotten” author. Those who needed to know about him have always had a way of finding him. As a young writer, interested in fiction and poetry, I knew a lot about storytelling from my elders. When inspired, they could make mundane errands and daily aggravations into the stuff of family lore. Even the quotidian humiliations of Jim Crow—having to switch to the segregated car when traveling to visit relatives for a funeral in Mississippi—became a story about traveling with fried chicken and pound cake in a shoebox that, in the telling, was as funny as it was infuriating. What I wanted was interesting ways of using language to see inside of things.

William Melvin Kelley is often described as a “lost” or “forgotten” author. Those who needed to know about him have always had a way of finding him. As a young writer, interested in fiction and poetry, I knew a lot about storytelling from my elders. When inspired, they could make mundane errands and daily aggravations into the stuff of family lore. Even the quotidian humiliations of Jim Crow—having to switch to the segregated car when traveling to visit relatives for a funeral in Mississippi—became a story about traveling with fried chicken and pound cake in a shoebox that, in the telling, was as funny as it was infuriating. What I wanted was interesting ways of using language to see inside of things.

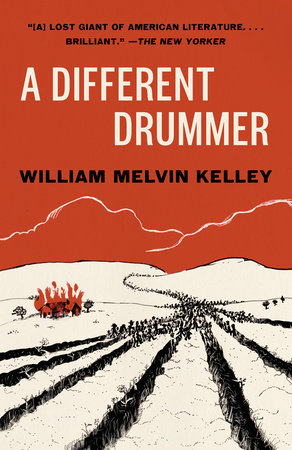

As I matured and studied literature and eventually creative writing, well-intended instructors and peers encouraged me to write “my own experience.” The models they offered, often White writers, didn’t create worlds in which I could see myself or breathe. I knew some Black writers, especially Richard Wright, who most people around me dismissed as a “protest writer.” But as is often the case when one is young, I knew the hunger but not the name for it, and lacking that name I didn’t know where to look or wait. I wanted a raucous style fit to capture the energy of the stories I knew. Eventually, as these things happen, someone steered me to Invisible Man. I loved Ellison’s sentences, and I loved many of the stories in that novel. But it always seemed to me that he saw his own particular black experience, but I couldn’t recognize myself in his sensibility. Then someone steered me to William Melvin Kelley’s A Different Drummer. I was not ready.

Kelley published his debut novel a decade after Invisible Man, which had won the National Book Award. It emerged in a context for me shaped by what would become the Black Arts Movement (for example, John Oliver Killens, Rosa Guy, John Henrik Clarke, Willard Moore, and Walter Christmas had already formed the Harlem Writer’s Guild, very much in the spirit of the famous salons Georgia Douglas Johnson led that helped shape the Harlem Renaissance). To my knowledge, although Kelley was based in New York, he was not affiliated with any of those organizations. He was one of many then who were searching, as I would in my own time, for ways to shape stories into plots in order to make Black life legible as meaningful and complex, and not wholly defined by the realities of oppression.

A Different Drummer is set in a fictional state between Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi, and the story is simple. Tucker Caliban, a descendant of an enslaved African whose story the novel presents in detail, buys a parcel of the land on which his ancestors had been enslaved, salts the earth, shoots his cow and horse, burns his house, and lights out, presumably heading north, triggering an exodus of all the Black people in the state. Its other antecedent is W. E. B. Du Bois’s 1935 Black Reconstruction in America, which Du Bois wrote at the urging of Anna Julia Cooper to challenge the conservative Dunning School narratives of the U.S. Civil War and Reconstruction. Within the first few chapters, Du Bois describes the self-manumission of enslaved people who joined Union camps en masse as a general strike, and argues that those formerly enslaved people reshaped the nature of the Civil War. If the Civil War had been about “states’ rights” (that is, the right of individual states to decide whether to maintain the institutions of slavery), the presence and influence of black volunteers made the abolition of slavery a primary aim. Could Kelley, whose story imagines what in effect is a general strike, have known Du Bois’s work?

What was most astonishing about this vision is that it emerges in the wake of Brown vs. The Board of Education (1954), the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott, and other events now associated with the postwar Civil Rights Movement. It is laceratingly critical of the idea of leadership, stressing instead the ability of ordinary people to act as political actors to determine their own fates. Most shockingly, at the time and even now, his characters are critical of organizations like the NAACP, and an amalgam of the Nation of Islam and Southern Christian Leadership Conference, all of which appear thinly veiled. I knew that members of my family and community criticized civil rights leadership, usually charging that those organizations had not gone far enough, but when I encountered Kelley’s work, I had never seen such criticisms in print. I didn’t know you could do that. As audaciously, he skillfully inhabited the perspective of working-class White characters who soon realize that with all the Black people gone they, the Whites, will occupy the bottom of the social order, ascribed to the same forms of labor, surveillance, imputed deviance, and policing.

Kelley’s work resonates because it shows that Black people are never invisible, never lost, but always ready to be “found.” He sensitively works through the ways racism gnaws at and corrupts interpersonal intimacies without focusing exclusively on heterosexual relationships across the color line. His worlds, in this novel and his other works newly available, are capacious and expansive, and his way with language ventilates even the toxic world of White men watching their world slip away from them. I have had to discover, forget, and discover him again. Above all, he reminds us of the unexhausted capacity of the imagination to see into impenetrable darkness and figure the world otherwise.

Anthony Reed is Associate Professor of English at Vanderbilt University. He is the author of Freedom Time: The Poetics and Politics of Black Experimental Writing which analyzes some of the ways black writers have engaged literary form to imagine new forms of aesthetic expression and political solidarity. His most recent book, Soundworks: Race, Sound, and Poetry in Production, studies recorded collaborations between poets and musicians within and beyond the Black Power era, is forthcoming.