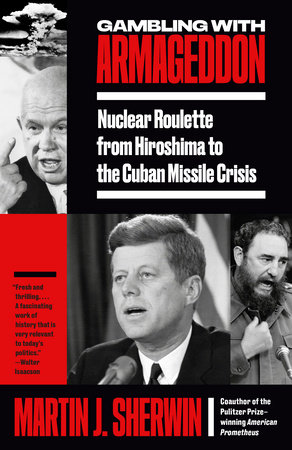

By Martin J. Sherwin

The Cuban Missile Crisis ended peacefully because neither President John Kennedy nor Premier Nikita Khrushchev wanted a war. It ended peacefully because Fidel Castro frightened Khrushchev into believing that the United States was about to start a war. It ended without a war because America’s ambassador to the United Nations, Adlai Stevenson, persuaded Kennedy that the crisis could be resolved diplomatically. It ended diplomatically because the president rejected the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s recommendation to attack Cuba.

And, despite all of the above, it ended peacefully because of luck, (“plain dumb luck” former Secretary of State Dean Acheson called it). Good luck, smart luck, or dumb luck intervened on several occasions during the crisis, but never more dramatically than on Saturday, October 27, 1962 At the last minute, a level-headed senior Soviet officer—randomly assigned to Soviet submarine B-59 patrolling in the blockade zone—prevented its captain from firing a nuclear armed torpedo at a flotilla of American warships that were dropping explosives to force his boat to surface.

Gambling with Armageddon was a book I had to write. Teaching the incident for over fifty years convinced me that it was the seminal event of the cold war. Yet there were matters that had not been studied, others that needed further study, and still others that I thought in need of reinterpretation.

I also admit to a personal interest. I wanted to know why I was still alive after those harrowing thirteen days. As the Air Intelligence officer of an antisubmarine warfare squadron in 1962, I was the custodian of our top-secret wartime deployment orders. On Monday, October 22nd, hours before President Kennedy announced that a blockade of Cuba was the first step to force Khrushchev to remove the Soviet medium range ballistic missiles he had secretly had installed there, I was directed to deliver those orders to my commanding officer and his senior staff. We were to deploy beyond the reach of those missiles, to an airfield in Baja, California. Some young bachelors in the squadron joked that Baja “would be a delightful place to die.” Until I researched this book, I did not know how close to death we had come.

The origins of the crisis are particularly interesting and a significant part of Gambling with Armageddon is devoted to them. Of course the Cuban Revolution was central, but neither Castro nor Communism can explain why Khrushchev chose strategic nuclear armed ballistic missiles to defend his new best friend. Seemingly an impetuous choice, it was dictated by the role that nuclear weapons had played in the preceding seventeen years of Cold War geopolitical competition.

The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, President Dwight Eisenhower’s massive retaliation policy, his deployment of intermediate range ballistic missiles to Turkey (about one-hundred-thirty miles from Soviet territory), and the administration’s aggressive brinksmanship, led Khrushchev to view strategic missiles as the deterrent du jour. The United States, he rationalized, “surrounded us with military bases and kept us at gunpoint [with nuclear missiles].” Sending similar weapons to Cuba would create “a balance of fear” and Cuba would be safe.

The crisis provides a unique window into presidential leadership, and my research yielded numerous surprises. Listening to the secret tape recordings of President Kennedy’s meetings with his civilian and military advisers was an amazing experience that I share with readers. How he analyzed the challenges and dangers the Soviet missiles posed is a window into a thoughtful, analytical mind.

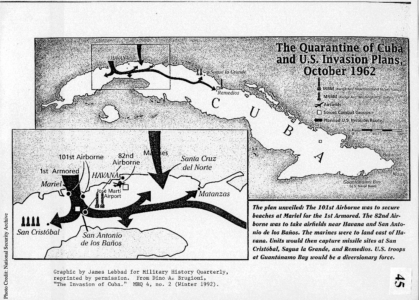

On the first day of the crisis, Tuesday, October 16th, Kennedy agrees with his advisers who are ready to bomb and invade Cuba. But over the course of the next several days—balancing the diplomatic advice he receives from Adlai Stevenson and former ambassador to the Soviet Union, Llewellyn Thompson—he becomes increasingly skeptical of the hawks (who periodically include his brother Bobbie—another surprise), and he reconsiders the consequences of his initial assumptions. The result is that the confrontation with Khrushchev begins with a blockade rather than an invasion that surely would have led to war for reasons I explain.

The crisis was not limited to the Soviet Union and Cuba. It was a global event far broader in its origins, scope, and consequences than its Russian name (the “Caribbean Crisis”), its Cuban name (the “October Crisis”), or its American name suggest. It was a global event, an integral part of the wider Cold War involving Berlin, Turkey, and all of America’s NATO and Asian allies.

As the president explains to the joint chiefs of staff (who are urging military action), the secret deployment of the missiles has provided the Soviets with a range of new options. “If we allow their missiles to remain, they have offended our prestige, and are in a position to pressure us. On the other hand, if we attack the missiles or invade Cuba it gives them a clear line to take [West] Berlin,” Khrushchev’s highest priority since 1958. That “leaves me only one alternative, which is to fire nuclear weapons—which is a hell of an alternative.”

So we are alive today because President Kennedy (and Khrushchev) understood that firing those weapons was—in Kennedy’s words—“the final failure.”