J. Gerald Kennedy is Boyd Professor of English Emeritus at Louisiana State University and a past president of the Poe Studies Association. Editor of the Penguin Classic The Portable Edgar Allan Poe, here he makes a case for Poe’s continued relevancy, 200 years after he was originally published.

Why read Poe? And why now? For starters, he’s a spell-binding storyteller. He has a knack for pulling you into a tale, creating edgy characters who find themselves in complicated situations. He projects the anxiety of someone on the edge. If you want a cool action hero, look somewhere else. Poe lived with poverty, fear, and desperation. His stories portray nervous, isolated characters in difficult relationships. In a Poe tale, home rarely represents a place of security, and love is mostly a thing already lost. Even though the author lived two hundred years ago, many readers find his outlook strangely contemporary.

Poe’s occasionally odd language or cryptic allusions intensify a modern story line. Current events have a way of making us appreciate his foresight. Part of the uncanny familiarity of Poe’s work comes from his relentless attention to extreme experience: violence, madness, cruelty, alienation, perverseness, and despair. Above all, Poe confronts the reality of death. Critic Daniel Hoffman once quipped that Poe is not the Samuel Smiles of world literature. But we live in a culture of fear, where political scare-tactics are rampant. Conspiracy theories excite social paranoia, while religious and ethnic hostilities foment tribalism. Nations threaten each other with ultimate weapons; global warming portends inescapable catastrophe. These are not ordinary times. And now we have a raging pandemic. It’s a perfect time to read Poe.

Poe doesn’t provide easy answers or emotional comfort. But he does portray nervous characters trying to survive. He helps us to understand where fear comes from, what it does to our thinking, how to understand and demystify it, even how to manage it. He gives us characters who subdue their panic by thinking rationally (see “The Pit and the Pendulum”), and he of course invented the detective hero. He learned to laugh at things that frightened him. From The Portable Edgar Allan Poe, here are five stories that portray dark realities but also capture hard truths.

“The Masque of the Red Death”

It’s a tale with a clock, and it couldn’t be more timely. We are facing a deadly pestilence that will stretch into 2021. It’s projected to take well over 200,000 lives in the United States, and worldwide deaths are likely to exceed one million. Is it even possible to read “The Masque of the Red Death” now without recognizing our sense of entrapment?

Poe wrote this tale in 1842, ten years after he survived the Asiatic cholera pandemic that ravaged the U.S. The contagion began in India a few years earlier and swept across Asia to Europe. According to a story Poe probably saw, it even disrupted a masked ball in Paris, causing guests to collapse in their costumes. When the pandemic reached the U. S., it decimated many cities. In Richmond, it took the life of a boyhood friend.

Then a resident of Baltimore, where nearly 3,700 died, Poe lived in one of the poorest neighborhoods where (then as now) epidemics tend to be deadliest. Wealthy citizens stayed safe by escaping to country estates. This cruel fact about economics and pandemics informs “The Masque of the Red Death.” Prospero shows contempt for the common folk and invites only privileged friends to his abbey. Then he bolts shut the door to exclude poverty and disease. But as we know, pandemics can also strike the seat of power.

“The Premature Burial”

Especially during contagion, when sanitation workers buried victims quickly, the danger of too-hasty burial increased. This fear, which seems to have arisen in the early 1700s, when science was on the rise and medical schools depended on fresh cadavers for dissection. It was really the only way to understand how bodies worked. While collecting corpses from local cemeteries, grave robbers occasionally discovered bodies twisted in their coffins. Sometimes they even found still-living victims, and a few survived, thanks to their unlikely rescue.

Meanwhile, medical experts studied the problem of apparent death and debated ways to avoid burying people alive. Some eperts advocated “waiting mausoleums” to hold bodies until they began to decompose. Just as this popular interest in death, cemeteries, and burial practices reached a peak, poets began writing about tombs and graveyards. In the 1750s, Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” became a hugely popular poem. Historian Philippe Ariès suggests that “the great modern fear of death” began in this era.

Controversy about hasty interment continued into Poe’s era and became one of his favorite themes. His tour de force, “The Premature Burial,” appeared in 1844. It begins as a documentary report on living burials. But then the tale takes an inward turn, as the narrator admits his own burial anxiety and slides into claustrophobic fantasy. But here the tale takes a last, crazy twist, leaving the reader surprised, relieved, and a bit deceived. It’s all a joke, but the tale works because premature burial stages a dress rehearsal for dying.

“The Man of the Crowd”

This tale from 1840 analyzes social fear. Poe was already thinking about the detective story, and his narrator boasts a talent for examination and diagnosis. Inspired by the early stories of Charles Dickens and by Poe’s boyhood memories of Regency London, “The Man of the Crowd” captures the curious isolation felt in a crowded city. Here Poe depicts a metropolitan social space teeming with tradesmen, shop girls, beggars, servants, strangers, pickpockets, inebriates, gamblers, prostitutes, and con men.

This tale dramatizes the insidious process by which a “frail” old man becomes first an object of curiosity, then a focus of suspicion and finally an emblem of depravity. Much depends on the narrator’s presumed reliability. As he plunges into the street, he reports seeing through a gap in the man’s cloak “a diamond and a dagger.” He describes the stranger’s bizarre movements, his attraction to crowds, and his uneasy backward glances. Poe implies that cities spawn deviant loners. But even though the narrator’s fierce pursuit discloses no misdeeds, he still declares this old stranger the epitome of “deep crime.” Maybe so. But Poe also hints that we manufacture social demons from our own twisted assumptions.

That’s because the “crime” story hides another story. From the outset—from the title, epigraph, and opening sentence—this narrator rivets our attention on the stranger. He’s compared to “a book that does not permit itself to be read.” But who is the real “man of the crowd?” Which character is more frightening—the frail old man scurrying around London or the obsessive-compulsive freak who tracks him for 24 hours? The narrator assures us he has never been observed. Should we believe him? With a handkerchief over his mouth (check it out), he follows the stranger everywhere, sometimes too closely. Once we perceive the narrator as a stalker, the old man’s behavior makes sense in an entirely new way. A hidden text becomes visible, one of mutual suspicion.

“The Murders in the Rue Morgue”

Poe launched the modern detective story with this 1841 tale. You’ll recognize all the key elements of CSI-style forensic dramas: a grisly crime scene, wildly conflicting testimony, and a locked room that makes the case seemingly insoluble. In C. Auguste Dupin, Poe invented the detective genius as well as his affable sidekick (our narrator) who shares the reader’s uncertainty. Then there’s the befuddled chief of police who can’t crack the case. Poe withholds the solution to the end, when Dupin stages a dramatic encounter that reveals all.

Though set in Paris, “Murders” also plays on racial tensions in Philadelphia, where Poe was then living. Three years earlier, anti-abolitionist rioters stopped an antislavery convention by burning down the meeting hall. An illustrator named Edward W. Clay stoked racism with offensive cartoons portraying blacks as apelike buffoons. Because most city barbers were black, Poe knew that his tale about a razor-wielding primate would exploit local anxieties. But he also detested rioting mobs and perhaps intended to mock Clay’s inflammatory racism.

There’s another reason why this story is important. Poe shows how newspapers and magazines were already cultivating a mass culture by playing to public fears. In “Murders,” news accounts provide lurid details about the deaths of two women, but they also excite alarm. Poe recognized an incipient “culture of fear.” This phrase, coined by contemporary sociologists, refers to our chronic modern anxiety, reinforced by troubling news stories about dangerous immigrants, terrorists, horrific diseases, cyber crimes, food shortages, etc.

“Hop-Frog”

Poe published this shocking tale in 1848 in an anti-slavery newspaper, and students may see how it relates to the conflict over slavery. The plot creates sympathy for Hop-Frog, the jester dwarf, and his tiny sweetheart, Tripetta, who receive cruel abuse from the king and his counselors. A bit like Poe himself, Hop-Frog doesn’t handle drink very well. But the jester’s gruesome revenge leaves most readers gasping. Do the ends justify the means?

There is no easy way to explain the ethics of “Hop-Frog.” It’s one of several Poe tales depicting a brutal crime, but here (unlike “The Tell-Tale Heart” or “The Black Cat”), there is no psychological fixation or fit of perverseness that sheds light on an unspeakable act. There is only injustice, which inspires a calculated, cold-blooded atrocity. Poe relates the story from a viewpoint sympathetic to Hop-Fron—though not uniquely from his perspective. Oddly, Poe adopts the tone of an old fairy tale.

Poe’s stories anticipate many horrors that pervade our twenty-first century culture of fear. “Hop-Frog” specifically offers a fresh angle on terrorism, for the masked ball suggested by the dwarf creates a horrible spectacle that sends a message. Fear of terrorism has subsided since 9/11, but anyone who remembers that day will recognize in “Hop-Frog” a preview of the terrorist plot: the powerless Hop-Frog outsmarts the king by inverting the symbolism of power. As one of the “Eight Chained Ourang-Outangs,” the king puts himself in slave chains to terrify his guests and flaunt his might. But Hop-Frog excites terror in the would-be terrorizer. Yes, Poe plays the race card again, but to what purpose?

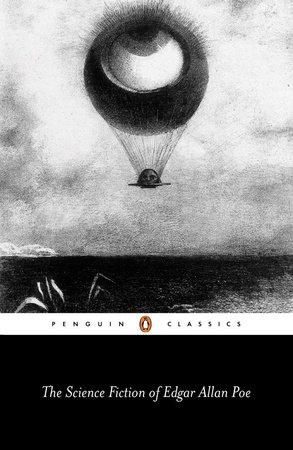

The Portable Edgar Allan Poe compiles Poe’s greatest writings: tales of fantasy, terror, death, revenge, murder, and mystery, including “The Pit and the Pendulum,” “The Fall of the House of Usher,” “The Cask of Amontillado,” “The Masque of the Red Death,” and “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” the world’s first detective story.

In addition, this volume offers letters, articles, criticism, visionary poetry, and a selection of random “opinions” on fancy and the imagination, music and poetry, intuition and sundry other topics.

See below for more of Edgar Allan Poe’s writing from Penguin Classics.