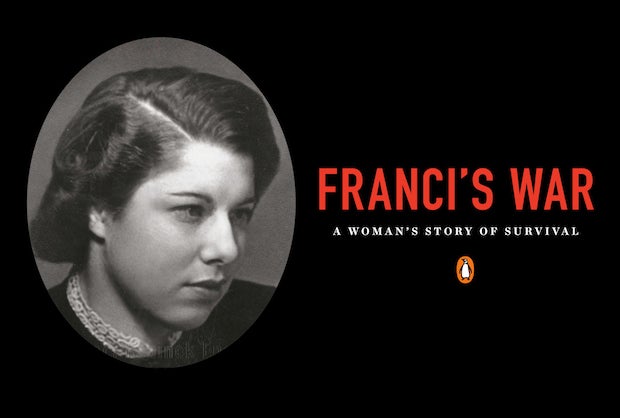

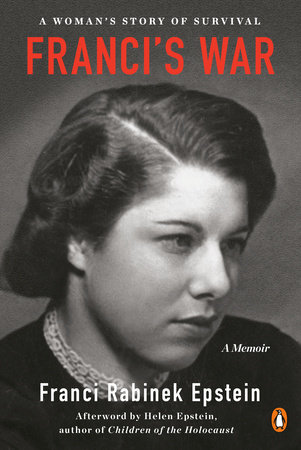

In 1942, 22 year-old Franci Rabinek arrived at Terezin, a concentration camp and ghetto 40 miles north of her home in Prague. It would be the beginning of her three-year journey through four different camps. Her memoir, Franci’s War, offers her intense, candid account of those dark years before her liberation in 1945.

Before that, though, Franci was living an increasingly restricted life in Prague, as Jewish citizens’ rights were being stripped away one by one. Her daughter Helen Epstein shares insights from her mother’s experiences as we face our own restrictions in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

I grew up with my mother’s near-daily stories of having survived not a pandemic, but the Nazi occupation. First, Franci—then a young Prague dress designer—had lived on lock-down for more than two and a half years after the German Army invaded Czechoslovakia in the spring of 1939. In the fall of 1942, she, her husband and parents were deported to a series of concentration camps. Finally, 75 years ago, she was liberated by the British Army from Bergen-Belsen on April 15 of 1945.

She wrote about her experiences in a manuscript she sardonically titled Roundtrip because it began and ended in Prague. It began as my mother had just turned 19 and had inherited the management of her mother’s fashion salon in the center of Prague. The plague that had been unleashed upon the world then was political rather than viral. As a Czech, she was part of a subjugated nation; as a Jew (as defined by having four Jewish grandparents), she was soon prohibited from going to work, to the movies, using public transportation, shopping for food, seeing a doctor, or her friends. Cooped up with her boyfriend and aging parents in a small apartment, she was bored, angry, frustrated and subject to ever-more-restrictive regulations.

How did Franci and her family cope? Reading her memoir on lock-down in my Massachusetts home, I pay attention to their strategies. Routines and strict organization of time was key. My grandfather’s first priority, she writes, was knowing exactly what was going on. He combined his need for exercise and need to know the latest news by walking miles across Prague every day to listen to the BBC at the homes of friends whose radios the Nazis had not yet confiscated. When he got back home, he updated his family, as well as the war maps he tacked to a wall, showing the progression of the Allied armies.

Franci’s enterprising boyfriend spent his time hatching anti-Nazi plans with his Czech army buddies and picking up useful items and food where he could. He soon bought Franci a puppy. Walking the dog—then as now—provided not only diversion but a necessary, recurrent and welcome reason to escape confinement, no matter the weather, and the entire family became dogwalkers

Since owning radios and phonographs was forbidden to them, Franci and her family had to generate their own music. They sang operatic arias and favorite popular songs with one another, vying to remember the lyrics. And they still had their books: volumes and volumes of literature that they could read and reread.

Somehow, we became accustomed to our strictly circumscribed existence, Franci writes in her memoir. At a loss for what to do with my abundance of free time, I began to clean house, waxing and polishing everything in sight. I also learned to cook a little, as much as our severely limited supplies allowed—mainly vegetables. I never again want to eat a carrot cake, or potato goulash, or any of the other concoctions of that time. Everyone started dying sheets and pillowcases dark colors so as to save on soap in the uncertain future. We all acquired large duffel bags and knapsacks at black market prices, to be packed within twenty-four hours if necessary.

By September 1942, Franci was so fed up with all the restrictions in Prague that she thought any change of scene would be a relief, no matter what was waiting on the other end. She missed going to the movies, seeing her friends, going for walks in the park. Of course, she could not imagine Terezin or Auschwitz, or Bergen Belsen.

Today, Franci’s matter-of-fact memoir of involuntary confinement can be read as a guide to getting through our own difficult times. How did she survive? Let me count the ways.

She refused to take her situation personally. She saw herself and her family as part of a far larger group of people whose lives had not only been disrupted but threatened by death. She refused to feel sorry for herself.

She followed her father’s lead and kept her eyes and ears open, assessing the news she heard, reading situations and people as best she could, and acting accordingly.

She kept her friends close and was lucky—when she was deported to the concentration camps—to be with old friends and find new ones while imprisoned with a group of young women who shared a common culture. She formed alliances where she could, even adopting and taking care of an orphaned child in Terezin and Auschwitz.

Of the many orphans needing surrogate parents in Terezin. Franci and her husband chose a young girl of twelve named Gisa: “She was suspicious of everybody, and it took me weeks to coax a smile from her. When we gave her a piece of chocolate, we discovered that she had never seen or tasted chocolate before. Gisa finally melted one day when I threw a few English words into our conversation with Joe. You speak English! she cried out. Will you teach me? She soaked it up like a sponge and also started to eat more and fill out a little. I made over some of my clothes for her, because the outgrown things she was wearing made her look even tinier than she actually was.”

Franci found meaning in such personal relationships as well as in feeling useful and performing work she knew how to do—in her case, adapting her sewing skills as needed. Instead of designing glamorous evening gowns, she applied herself to the task of repairing blood-stained Nazi uniforms in the forced labor workshops she was assigned to and, after hours, patched together clothing for herself, her friends, and for favors and food.

In the absence of an internet, she sought diversion and solace in her store of favorite memories, memories of her parents, of her first unrequited love—an architecture student from Dresden named Leo, of her favorite poems, stories, plays, and songs.

She took one day at a time and clung to the conviction that she would get through whatever happened.

Franci often referred to the concentration camps as her “university,” where she had received a unique education in human behavior. Her greatest concern was that due to human nature, what happened to her could happen again in a different form, to anyone, anywhere in the world. She would have been dismayed but not devastated by COVID-19. She would have told her children and grandchildren that they had to pay attention and never lose hope that they’d get through it. I am finding her legacy invaluable now.

Read more about Franci’s experiences in Franci’s War, available now.

Helen Epstein’s Holocaust trilogy of non-fiction titles includes Children of the Holocaust, Where She Came From, and The Long Half-Lives of Love and Trauma.