Contributed by T. Christian Miller and Ken Armstrong, authors of the book Unbelievable

In journalism we have a word for a story that resonates, that gets passed around and talked about, that so engages or infuriates or floors its readers that they feel compelled to share it with someone else. This kind of story forces a reaction. It demands follow-ups. It can change the way people think.

We say the story has legs.

When we first started reporting what would become “An Unbelievable Story of Rape,” we knew the story had legs. At its heart is a young woman, named Marie, who was victimized twice over. First she was raped. Then she was branded a liar. Authorities in Lynnwood, Washington, charged her with filing a false report. Two and a half years later, 1,300 miles away, brilliant police work by two detectives in Colorado led to the capture of a serial rapist. In his possession the police found evidence that he had raped Marie, photographs that left no doubt Marie had been telling the truth all along.

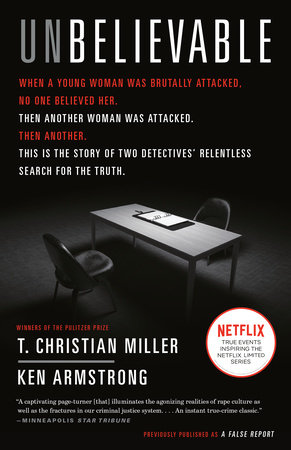

When our story was published online by ProPublica and The Marshall Project, it hit like a thunderclap, getting passed from reader to reader at remarkable speed. The article, read by millions, won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting. In February 2016, working with producer Robyn Semien, we helped turn the story into a one-hour episode of This American Life. That episode, heard by millions, won broadcasting’s prestigious Peabody Award, lauded as “a chilling indictment of doubt [and] a harrowing picture of the vilification . . . the victim suffered.” In 2018 we published a book on this case, A False Report: A True Story of Rape in America. The book met with outstanding reviews (“riveting,” O, The Oprah Magazine; “an instant true-crime classic,” Minneapolis Star Tribune; “Miller and Armstrong tell their story plainly, expertly and well,” The New York Times), and was translated into Chinese, German, Russian, Bulgarian, Turkish, Spanish, Portuguese, even Catalan. Its evangelists include author Susan Orlean, attorney Bryan Stevenson, and actress Merritt Wever. Then, in September 2019, Netflix aired Unbelievable, an eight-part dramatized series based on our reporting. This set off yet another thunderclap, four years after the first. Across all the major streaming platforms, the show, critically acclaimed as “revolutionary” and “TV’s most humane show,” was binged more than any other for three weeks running; it was viewed by 32 million households in its first 28 days.

What’s striking about all these readers, listeners and viewers is this: The story is no easy one. The people are nuanced. The lessons are varied. The impact is devastating. Unbelievable was described, time and again, as one of television’s most difficult watches, even as people kept hitting play.

The story—centered on doubt, how it started, how it spread—speaks to rape culture; misconceptions about trauma; police work, good and bad; the power of journalism; and forgiveness. These are important and timely issues for all of us, but they are especially urgent in the university context. Because as horrible as Marie’s case is, it is not unique. For centuries, courts instructed jurors to be skeptical when women report sexual assault. And, in part because of this history, many survivors of sexual assault remain quiet about their experiences, choosing not to go to police or campus authorities. It is essential that we create conversations on campus around sexual assault, especially as research indicates that more than 1 in 10 college students will experience sexual assault. But creating those conversations can be difficult.

Our book would help open the door to those difficult, and necessary, discussions. It’s already doing so on the classroom level: In universities from Princeton to Penn to Parkland to Central Oklahoma, professors have assigned our work in classes on psychology, journalism, criminal justice, feminism, and social work. Bob Woodward assigns our story as a model of how to merge investigative reporting with narrative writing. A criminal justice professor at Moraine Valley Community College tweeted that the story has “generated SO much” discussion, saying “students that typically don’t share in class, are talking a lot.” Our book is rooted in extensive research, allowing students to dig into source notes and learn more, be their interest an arcane FBI database or the teachings of a 17th century jurist whose misogynistic views shaped our law. It also offers numerous opportunities to engage other forms of media, including the radio program (permitting students to hear Marie’s voice) or the Netflix series (widely praised for eschewing sensationalism in favor of insight).

This is a story that people want to talk about and share. Our book can bring students into that conversation.

The authors, both reporters at ProPublica, can be found on Twitter at @txtianmiller and @bykenarmstrong