Dear Educators:

A few years ago, when I began to focus more on entrepreneurial pursuits, my mom, a former writer herself, gifted me a little book titled Passion: Every Day. It was filled with inspiring quotes like “I dare you, while there is still time, to have a magnificent obsession” and “follow your desire as long as you live.” This book is not unique. It’s part of a larger canon that portrays passion in an uber-positive light. The key to a good life, these books argue, is finding your passion and then following it wherever it leads. This is an especially prevalent narrative in technology, where passion is considered a prerequisite for lots of jobs. There’s only one problem: all these books and the narrative they spawned are wrong.

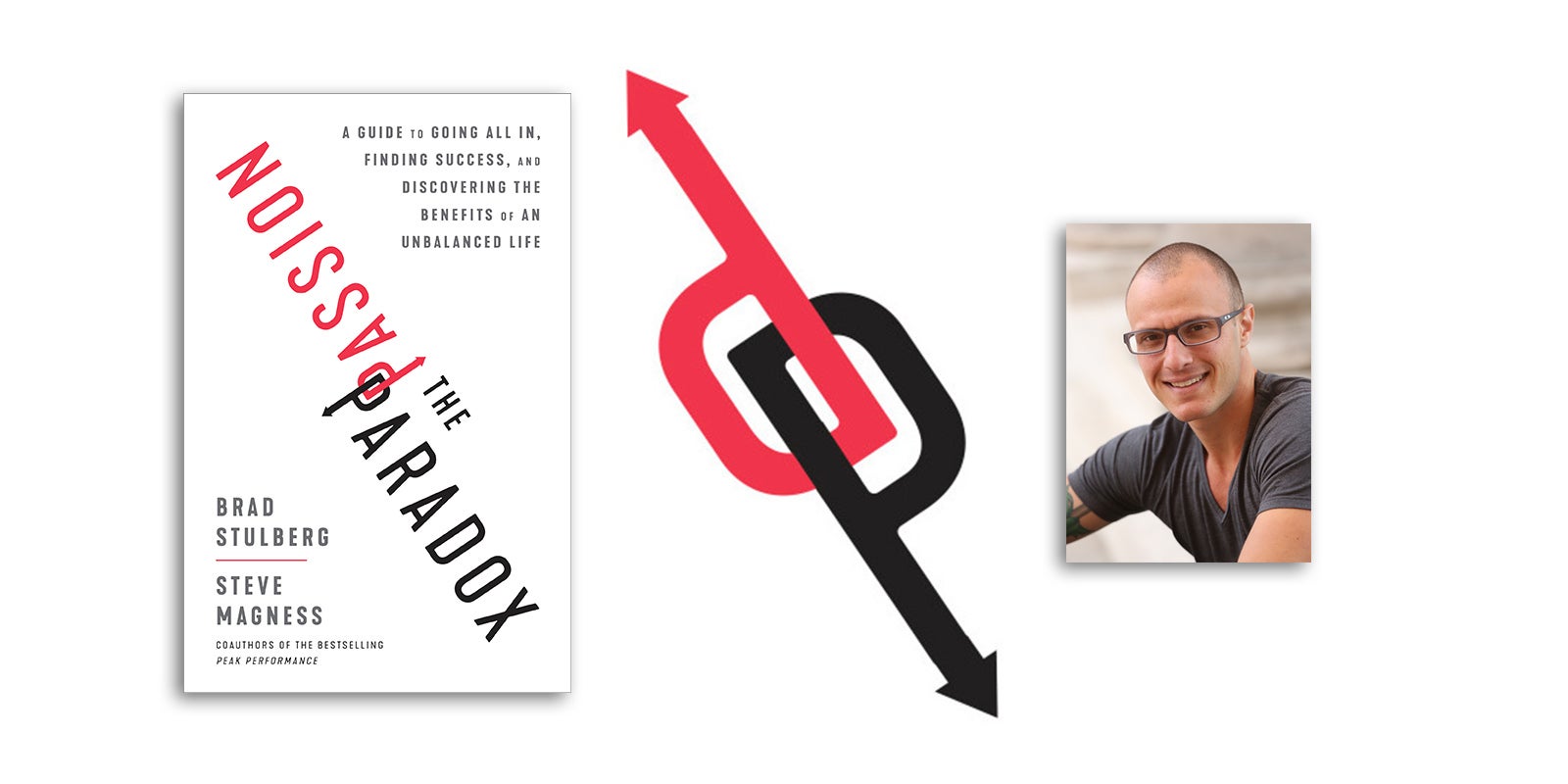

Passion is far more nuanced than most people think, and, as I explain in my new book, The Passion Paradox: A Guide to Going All In, Finding Success, and Discovering the Benefits of an Unbalanced Life, a superficial understanding of passion leads many people to suffer unnecessarily.

I spent over three years researching and reporting on the science of passion. I spoke with researchers from across academic fields (e.g., neurochemistry, psychology, philosophy, biology, psychiatry, management) and also with some of the world’s most passionate high-performing individuals. Here’s a brief summary of what I learned.

For starters, very rarely do people just magically find their passion. Yet most people expect to. In the small but growing world of passion research, this is called a “fit mind-set” of passion. Individuals with a fit mind-set of passion believe happiness comes from finding an activity or job about which they are immediately passionate, something that feels intuitively right from the get‑go. Over 75 percent of people hold this kind of mind-set. While this mind-set may be most prevalent, it’s not necessarily best. Individuals who adopt a fit mind-set of passion tend to overemphasize their initial feelings. They are more likely to choose pursuits (and especially professions) based on preliminary assessments, not potential for growth—even though the latter is generally more important than the former for lasting fulfillment and satisfaction. People with fit mind-sets for passion are also more likely to give up on new pursuits at the first sign of challenge or disappointment, shrugging their shoulders and thinking, I guess this isn’t for me. Furthermore, studies show that individuals with fit mind-sets actually expect their passions to dwindle over time, setting themselves up for midlife crises once their initial enthusiasm for an activity has diminished, and also, burnout—something especially widespread amongst millennials, who were sent off into the workplace with “find your passion” commencement speeches.

Better than a fit mind-set is a “development mind-set” of passion. Here, individuals understand that they will have to cultivate and nurture their passions over time; they don’t expect things to be great from the get-go; and they realize there will be highs and lows—seasonality, if you will—to their passions. The difference between a fit mind-set and development mind-set of passion is similar to the difference between a seeker and a practitioner. A seeker goes from one thing to the next, always chasing an illusory perfect. A practitioner knows that perfect is something that they must create and re-create over time. (Not surprisingly, research on romantic love—a close cousin to passion—demonstrates the same theme, which is perhaps especially strong in the age of online dating, where the possibilities for finding someone who is “perfect” from the outset seem endless.)

What’s more is that research on entrepreneurs shows that those who pursue their passions gradually and over-time on the side, “while keeping their day jobs,” have a greater likelihood of long-term success than those who quit their day jobs to go all-in from the get-go. Going all in brings with it pressure and, paradoxically, leads people to take less risks. Go big or go home and you often end up home. Go fast and break things and you often end up broken. But small and consistent steps over time lead to big gains.

Another big misconception about passion is that it’s always a good thing. In the psychological literature, there is a strong distinction between what researchers call harmonious passion and obsessive passion. In harmonious passion you pursue an activity because you love the activity. In obsessive passion you pursue an activity because you love the external results and validation you get from doing it. The former is associated with wellbeing and life-satisfaction. The latter is associated with depression, anxiety, burnout, and unethical behavior.

Far too many people start out with harmonious passion and, once they start achieving good results in their chosen field, shift toward obsessive passion, often without even realizing it. This is a dangerous trap because once someone with obsessive passion experiences a poor result—which is inevitable at some point—they often result to negative behaviors. Obsessive passion can ruin careers and lives. Studies of athletes show that those who demonstrate obsessive passion are far more likely to use illicit performance-enhancing drugs (e.g., Lance Armstrong). And in tech, individuals like Elizabeth Holmes have followed their craving for relevance and external results to massive fraud. Obsessive passion can even creep into parenting: look no further than the unfolding college admissions scandal, where parents became overly focused on achieving external results for their children—literally at all costs.

The book also explores the conflict between being “passionate” and being “balanced” and why self-awareness is the number one capacity to help you navigate this paradox. Finally, the book addresses the challenges of merging your passion with your identity and explores how to transition out of a passion while minimizing the risk of depression, anxiety, and substance abuse.

I feel this book will add much value to the education of college and university students and that these topics of discussion are important ones to be having so future generations can offer a correct narrative on passion, a concept that won’t be leaving the forefront of the culture any time too soon.

Brad Stulberg

Author of The Passion Paradox and Peak Performance

Visit the author’s website at www.bradstulberg.com and follow him at @BStulberg on Twitter