It has often been pointed out – first by the Greek poet Archilochus, and then more thoroughly in an essay by Isaiah Berlin – that writers can be classified as foxes, who know and are interested in a wide variety of different things, or as hedgehogs, who specialize, burrowing deeply into a single issue or interest.

Of course most writers don’t typically fit like wooden pegs into one category or the other; personally, I like to think of myself as a hybrid – perhaps a hedge-fox. Picture me with a low-riding, quilled chassis and a flamboyant, expressive and flame-colored tail.

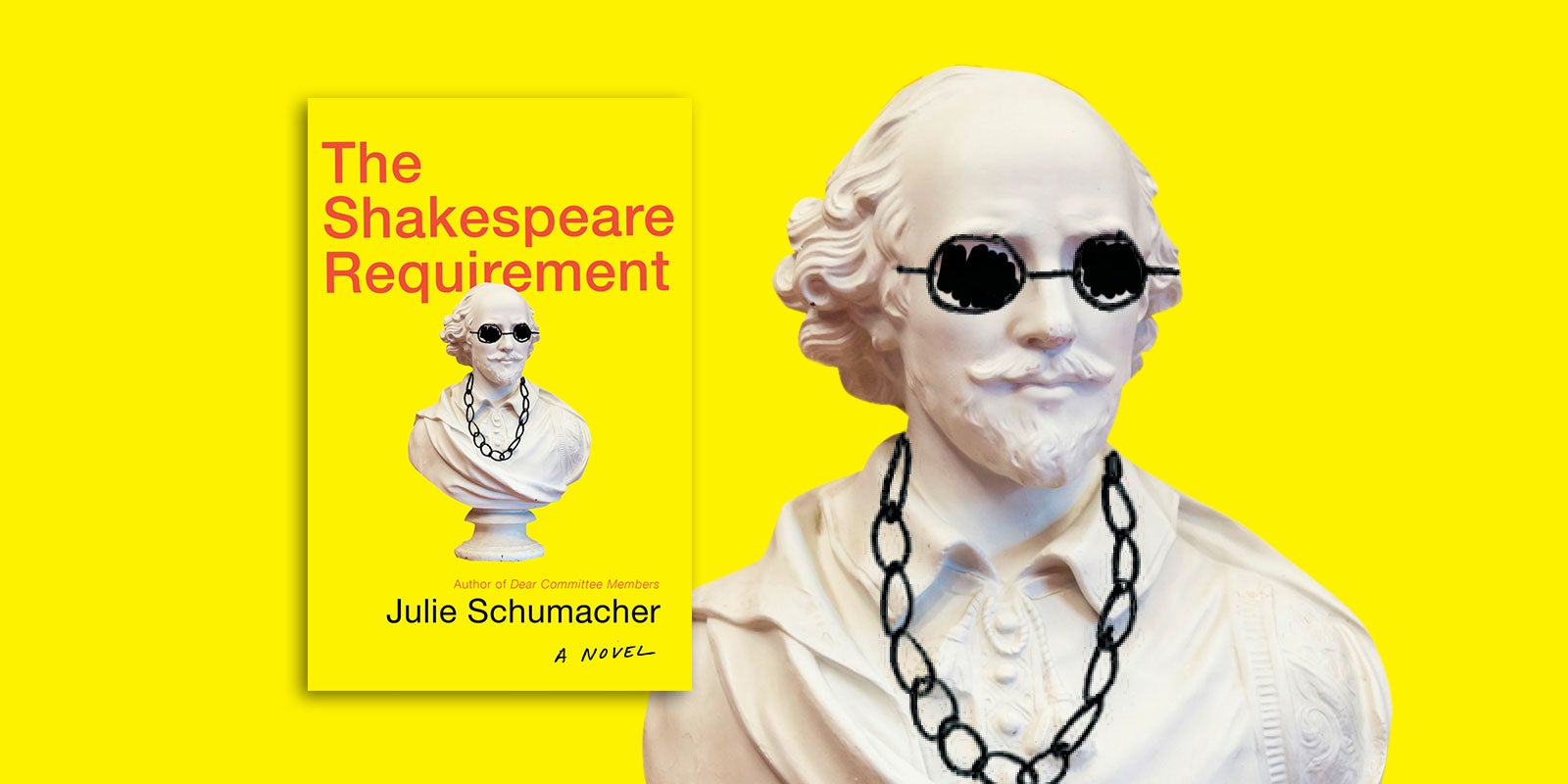

Fox-wise, I’ve written a range of different works: short stories, essays, young adult fiction, a coloring book, an epistolary novel, and two academic satires. As the only woman who has (so far) received the Thurber Prize for American Humor, I’ve been called a “comic writer” – a curious designation, given that a good deal of my fiction is depressing or sad.

Hedgehoggishly, I stick to realism that emphasizes character and emotion. No matter the genre, I write to find out who people (myself included) are: how they think and what they believe or fall in love with or fear. The old writerly saw – “write what you know” – is invariably misunderstood in this context. It doesn’t mean that writers should limit themselves to their own biographical experience, but that they should deeply understand the lives and emotions and psychology about which they write. A novelist with an intimate or insightful knowledge of loss can depict that emotion in her own back yard or on Planet Glyx.

The way in which I fail as a hedgehog regards research. To my mind, a true hedgehog is a writer who investigates the details of her material with a thoroughness I don’t have the patience for. Look at (among the marvelous books I’ve read recently) Yaa Gyassi’s Homegoing, or Kevin Powers’s A Shout in the Ruins, or Joan Silber’s Improvement or Rachel Kushner’s The Mars Room. Just thinking about the amount of work Hilary Mantel must have done for her novels makes me feel tired.

Because I lack that dedicated sort of attention span, my own idea of literary research would fall under the heading of dilettante-fox. Most of what I need in order to write my books can be found in my own jumbled brain or in Britannica Kids. That said, while writing Dear Committee Members I kept a beloved copy of Mrs. Byrne’s Dictionary of Unusual, Obscure, and Preposterous Words close at hand. And in the process of writing The Shakespeare Requirement, I spent some significant time on what might best be termed “research lite” via the net. Having kept tabs on some of the topics I investigated while writing the book, I offer the following list:

miniature donkeys, diet and behavior

how to make campaign buttons

vicodin vs. percocet – effects

Biblical concept of “headship”

komodo dragon vs. monitor lizard

cauliflower ears

types of yoga

choking sensations; drowning; Heimlich maneuver

Roman gladiator – gladiator wardrobe

at what height is a person considered a midget?

ten of the world’s most erotic statues

are wasps insects?

Shakespearean references to grief

illnesses contracted from toilet seats

celebrity deaths, fall 2010

Latin translation of _______ [multiple instances]

international transport of tarantulas

The list is clearly more fox than hedgehog, especially if the fox in question has ADHD.

Fortunately, while writing the book, I also had access to primary sources: that is, undergraduate English majors, whom I quizzed about their attitudes toward the work of Shakespeare. For students concentrating in English, should a semester of the bard, I asked them, be required? Opinions were divided on the subject: some students believed it wasn’t necessary to require a semester-long class dedicated to a single (dead white male) author, when there are so many important works to read; others worried that removing Shakespeare as a foundation of the curriculum would be akin to extracting the skeleton and leaving a lump of flesh behind.

I did find it reassuring to hear one student, discussing the relevance of centuries-old literature, explain that “Beowulf changed my freaking life.”

Fox and hedgehog alike must equally aspire to any portion of that readerly zeal.

About the Author

Julie Schumacher grew up in Wilmington, Delaware, and graduated from Oberlin College and Cornell University. Her first novel, The Body Is Water, was published by Soho Press in 1995 and was an ALA Notable Book of the Year and a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award and the Minnesota Book Award. She lives in St. Paul and is a faculty member in the Creative Writing Program and the Department of English at the University of Minnesota.