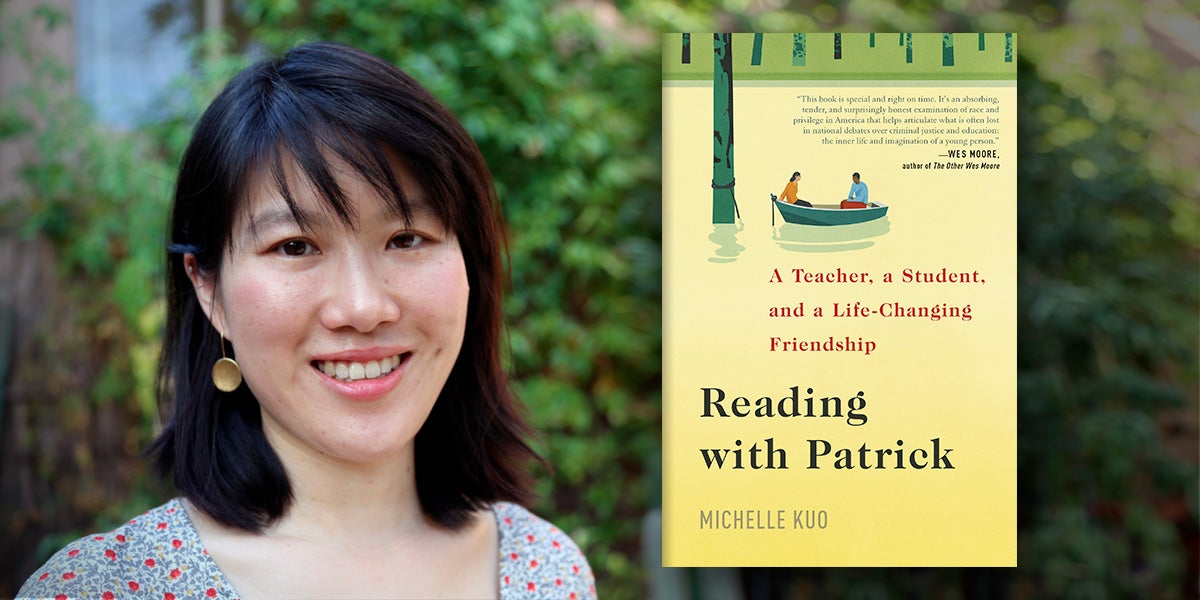

By Michelle Kuo, author of Reading with Patrick (Random House, July 2017).

By Michelle Kuo, author of Reading with Patrick (Random House, July 2017).

Every teacher has likely experienced two emotions: the feeling that you’ve gotten through to a student and the feeling that you’ve let him down. In the first, the classroom is a powerful place of human connection, and the lightbulb that has gone off in the kid’s head is hot and radiant. In the second, life proves too complex, too full of barriers and missteps, and the teacher, with regret and perhaps some shame, retraces her decisions, dissecting what went wrong.

My book, Reading with Patrick, explores these two emotions in regard to one student: Patrick, fifteen, bright and thoughtful, whom I met while teaching in the rural town of Helena, Arkansas, located in the heart of the Mississippi Delta. Just as Patrick started to make gains in my classroom, I decided to leave and go to law school. Two years later, I discovered that he had dropped out, gotten into a fight, and killed someone. I returned to visit Patrick in county jail, where he had been charged with first degree murder. I found that he could no longer write a simple sentence. I moved back to Arkansas and, for the next seven months in a windowless interrogation room, we read every day: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, Frederick Douglass, and James Baldwin. We memorized poetry by Merwin and Whitman. He wrote extraordinary letters to his daughter, who was a year old. It was only when I was halfway through my time there that I realized what we were doing—trying to resurrect roles that we previously failed at.

My book explores questions that idealistic students who seek to tackle social injustice might be moved to ask: can you change a life? Is it arrogant to think you can? Perhaps even more deeply, students can ask: What is a human connection made of? Who do we choose to connect with? If two people are from unequal circumstances, is the connection compromised from the start? No matter the answer, is it still possible to create moments that are transcendent and imaginative, in which suddenly those differences don’t matter, where stories, poetry, and love of words can connect you?

Patrick and I come together when we read, and, I think, both of us experience the magic of internal transformation. But my book, I’m anxious to stress, is not a “teacher savior” story: At the end of book, after serving his time and being let out of prison, Patrick is hardly saved. He is still struggling—to find a job, to make a place for himself, to forgive himself for his crime. As for me, I have left the Delta not once but twice—the Delta is a place where people with means leave—and, in so doing, let Patrick down. Students might ask whether internal transformation, and the comfort and knowledge it brings, matters if it cannot reduce inequality.

Teachers interested in criminal and racial justice might also use the book to introduce questions including: What factors lead to crime and especially violent crime? What’s the difference between murder and manslaughter, and what sentence does Patrick “deserve”? Patrick was a peaceful kid who kept to himself, who managed against all odds until he was eighteen to stay out of fights and stay out of trouble. Then he was arrested for murder. How do we end up here? My book pushes back against the tendency to think: “I wouldn’t have done that, I would have done something different”—as if there looms a superimposing I, a conscience or soul or clear mind that is consistent and knowable, irrespective of context. The book may help students who are very different from Patrick to imagine his place in America, a rural town in one of the poorest regions of the country.

Teachers seeking to teach the legacy of race in American history in a more intimate, story-driven way can also use Reading with Patrick. The Delta was once stomping grounds of the civil rights movement, where Martin Luther King marched and Bobby Kennedy visited. It was here that Stokely Carmichael coined the term Black Power. Today, the place doesn’t exist on the national radar. The Delta has one of the lowest literacy rates in the country, and this should feel like a very painful fact, one that challenges us to face American history and ask where we are now. This is a region of the country whose poverty is directly traced to the effects of slavery and sharecropping. It’s still poor. It’s majority black. Literacy can be seen as a central battle for enfranchisement today. High school students will realize, even more directly and viscerally than most other readers, how far behind Patrick and his classmates are with their writing and reading.

Last, many teachers find themselves in the crucial—and often uncomfortable—role of expanding the minds of students who come from families or environments that espouse narrow or conventional ideas of success. Reading with Patrick describes the pressure I faced from my immigrant parents—to make tons of money, to obtain a high status job, to move away from Arkansas, to become a doctor or engineer (professions prized in their native Taiwan). Students can reflect on my choices: Why did I really leave Arkansas and go to law school? Should I have left? What mistakes did I make? Did I live by the ideals I set out for myself? I describe my hesitations, weaknesses, and privilege as honestly as I know how. I hope this vulnerability can, in turn, encourage each reader to “evaluate his experience honestly,” as Ralph Ellison once described the project of the writer. For this reason, teachers of narrative or personal memoir may also use this book as a sample or guide.