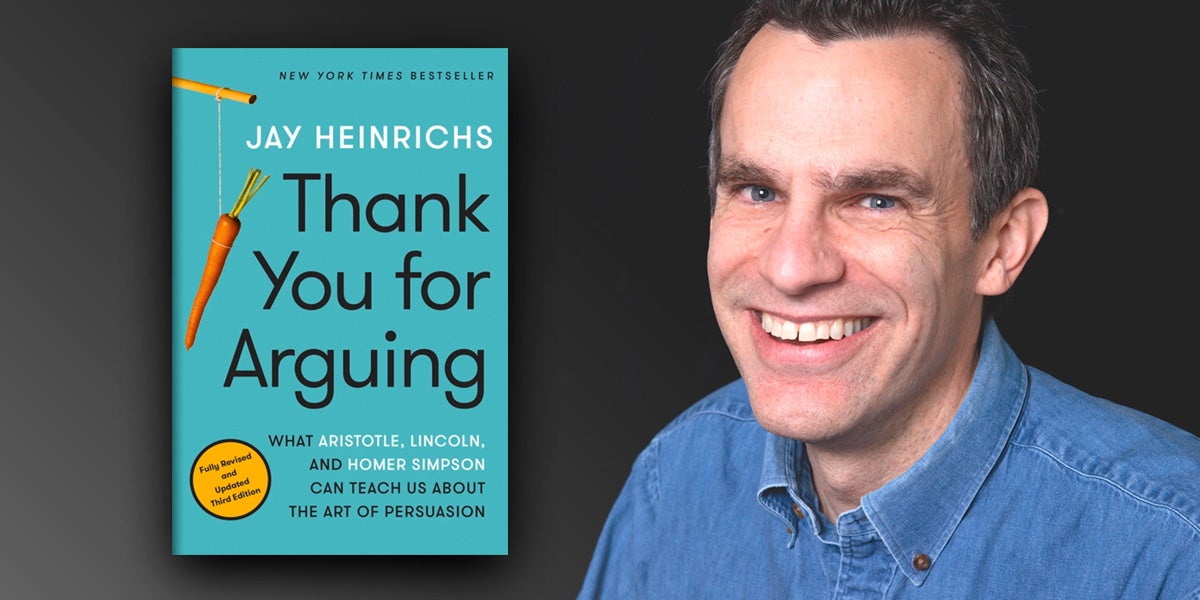

By Jay Heinrichs, author of Thank You for Arguing, Third Edition (Three Rivers Press, July 2017).

By Jay Heinrichs, author of Thank You for Arguing, Third Edition (Three Rivers Press, July 2017).

Adding rhetoric to a literature syllabus can spark something surprising in students.

Few people can say that John Quincy Adams changed their lives. Those who can are wise to keep it to themselves. Friends tell me I should also stop prating about my passion for rhetoric, the 3,000-year-old art of persuasion.

John Quincy Adams changed my life by introducing me to rhetoric.

Sorry.

Years ago, I was wandering through Dartmouth College’s library for no particular reason, browsing through books at random, and in a dim corner of the stacks I found a large section on rhetoric. A dusty, maroon-red volume attributed to Adams sat at eye level. I flipped it open and felt like an indoor Coronado. Here lay treasure.

The book contained a set of rhetorical lectures that Adams taught to undergraduates at Harvard College in the early nineteenth century, when he was a paunchy, balding, thirty-eight-year-old United States senator.

Adams urged his goggling adolescents to “catch from the relics of ancient oratory those unresisted powers” that, he assured them, “yield the guidance of the nation to the dominion of the voice.”

Unresisted powers. They sounded more like hypnosis than politics, which was sort of cool in a Manchurian Candidate kind of way. And yet, I felt as if I were about to fill a vast gap in my life.

As it turns out, rhetoric is filling an even bigger gap. Little did I know that Common Core State Standards would increase the demand for rhetorical skills. These days, the Core requires teachers and students to employ literacy standards beyond Language Arts. Thank You for Arguing seems to be filling that demand. I offer free Skype-ins with classes that adopt the book (let me know at ArgueLab.com if you’re interested!). They tell me they love the book. AP®educators have also been putting positive reviews on Amazon. Here’s a typical one:

“Great intro to a tough subject for new students. Funny and entertaining, too.”

Thank you, State Standards. But we’re talking about more than the Common Core here. Like you, I was a bookish child, absorbing everything I could from works on the Bobbsey Twins to those by Ursula K. Le Guin. But I wondered whether there was something to words besides art. I felt like a young Dylan Thomas receiving books “that told everything about the wasp, except why.” Could words get up and make a living for themselves? Could they be useful somehow? Could they change people, maybe the world?

And then I found rhetoric. The ancients considered it the essential skill of leadership, knowledge so important that they placed it at the center of higher education. It taught them how to speak and write persuasively, produce something to say on every occasion, and make people like them when they spoke. After the ancient Greeks invented it, rhetoric helped create the world’s first democracies. It trained Roman orators such as Julius Caesar and Marcus Tullius Cicero, and it gave the Bible its finest language. It even inspired William Shakespeare. Every one of America’s founders studied rhetoric, and they used its principles in writing the Constitution.

In short, I found the why of words. Rhetoric gives a real purpose to a liberal education, pulling together all of a student’s knowledge while giving her the tools to inspire others. It inoculates her against the kind of manipulation and tribalism that poison our politics. It creates a good citizen. A truly educated one.

You might say that while I was standing in those library stacks, rhetoric talked me into itself.

For videos, blog, quizzes, tips for educators, and more, visit the author’s website: www.ArgueLab.com/for-educators