Who Was Langston Hughes? In 1925, twenty-three-year-old Langston Hughes was working as a busboy, clearing tables at the Wardman Park Hotel in Washington, DC. One day, he read in the newspaper that a very famous poet named Vachel Lindsay was in town. Mr. Lindsay, a white man from Illinois, was scheduled to read his poems at the same hotel where Langston worked.

Langston had seen many famous people at the hotel. Important politicians and diplomats stayed there all the time. But they didn’t excite Langston. The idea of meeting a famous poet did.

Langston, who wrote poetry every chance he could, desperately wanted to attend the poetry reading. But he knew the hotel didn’t allow Black people into the auditorium.

That day, during his shift, Langston saw the poet eating in the dining room. He recognized him from the picture in the newspaper. Langston knew that he could lose his job if he tried to talk to Mr. Lindsay while he was eating, but he had to do something!

Langston wrote out three of his own poems and put them in his pocket. When no one was watching, he walked up to Mr. Lindsay. He didn’t know what to say to such a famous poet. So he simply told the man how much he admired his poems. Then Langston reached into his pocket and quietly put his poems on the table. Then he hurried back to the kitchen.

Later, while Langston was clearing a table, he saw Mr. Lindsay reading the poems he had handed him!

What Langston didn’t know was that Mr. Lindsay later read those poems aloud to the large audience who had come to hear him speak. No one expected Vachel Lindsay to read poems by someone else. Especially not poems by a Black man who worked at the hotel! But the people in the audience liked Langston’s poems.

The next morning, on his way to work, Langston read the newspaper again. This time, there was an article about

him! The piece explained that Mr. Lindsay had discovered a “Negro busboy poet.” (

Negro was a word used to describe Black people at the time. Today, it is considered offensive.)

When Langston arrived at work, there were reporters waiting. They interviewed him and took his picture. They asked him to pose wearing his white uniform and hat, holding up a tray of dirty dishes in the middle of the dining room.

Langston didn’t want to tell the reporters they were wrong. In a sense, Vachel Lindsay

had discovered him. It wasn’t often that he had

white readers. But in Harlem, a mostly Black neighborhood in New York City, Langston had already been discovered. In fact, he was very well-known there to a huge Black audience, and his first book was about to come out from a major publisher.

The story about Langston Hughes was soon reprinted in newspapers from Maine to Florida. No one had ever heard of a “Negro busboy poet,” and everyone wanted to see what Langston looked like. Langston was happy to have the publicity.

Back at the hotel, there was a package waiting for Langston. It contained books that Mr. Lindsay had left for him. The poet had also written Langston a long note, full of helpful advice. Langston followed that advice and quit his job at the Wardman Park Hotel. It wasn’t long before people all over the country—and the world—knew about Langston Hughes.

Langston went on to be the most famous African American poet there has ever been. In fact, he’s among the most famous American poets of all time. More famous than even Vachel Lindsay.

Chapter 1 Growing Up Black James Mercer Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, on February 1, 1902.

Langston’s father had studied law. But he was not a lawyer when Langston was born. Black people in Missouri were not allowed to be lawyers at that time. Even if Mr. Hughes moved Langston’s family to a state with fairer laws, it would not have helped. White clients would not hire Black lawyers. And few Black clients could afford a lawyer at all.

Langston’s father had little hope that things would improve for his family. Mr. Hughes wanted to leave the United States. In Mexico, he could practice law. Langston’s mother didn’t speak Spanish, so she could not work there. But she agreed to learn. And they decided to move. But Mexico was not what they expected. When they arrived in Mexico City, in April of 1907, there was an earthquake! Sidewalks and streets cracked open. Tarantulas and scorpions climbed out of the walls! Langston’s mother was not happy. She immediately decided to return with Langston to the United States. Mr. Hughes stayed. Langston’s mother got a job in Topeka, Kansas. But the job didn’t pay enough for her to take care of Langston. She wanted her son to have a happy childhood. She sent him to live with his grandmother, Mary Langston, in Lawrence, Kansas—at least until she could find a better job.

Mary, whose family name young Langston had been given, was one of the first women to attend Oberlin College in Ohio. She had been married to two abolitionists, people who fought to end slavery. Her second husband, Langston’s grandfather, was a political activist. He was the brother of John Mercer Langston, the first African American from Virginia elected to the United States Congress. Mary Langston told her grandson stories about all these men, along with other Black leaders and freedom fighters.

Mary Langston was a proud woman. Her grandmother was Cherokee and her grandfather was a French tradesman. And though Mary was Black, none of her ancestors had been enslaved. So she refused to do work once reserved for enslaved people. She never washed strangers’ clothes or cleaned other people’s houses. Instead she made money by renting rooms in her house.

Mary and Langston lived modestly. They ate salt pork and wild dandelion greens. For entertainment, Mary would sit in her rocker and talk to her grandson. She read to him from the Bible and told him long stories from memory.

Washington and Du Bois At the turn of the twentieth century, Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois were the two leading Black social reformers. They had very different ideas of how to solve problems of race in the United States following the Civil War.

Washington had been born into slavery in Virginia and believed Black people should try to fit into the communities where they lived. He stressed education, with an emphasis on practical job skills. Washington told his followers that financial stability came from working hard and would earn them the respect of their white neighbors.

Du Bois was born free in Massachusetts and believed Black people should move to areas of the country that were more accepting. He stressed education, with an emphasis on writing and other forms of expression. Du Bois told his followers that by creating and celebrating a uniquely African American culture, Black people would earn the respect of white Americans. She also taught young Langston about history. She told him about the town of Lawrence, where they lived. It had been founded by abolitionists, both Black and white. Lawrence had once been a meeting place for people who didn’t believe in slavery. Everyone was allowed to enter the churches, hotels, restaurants, and other businesses, regardless of their race.

By the time Langston moved to Lawrence in 1908, though, the town had changed. It had become segregated, with strict rules about where Black people were allowed to go.

White boys Langston’s age could swim at the YMCA or join the Boy Scouts. They could take part in school track meets and watch Charlie Chaplin movies at the theater. Langston could do none of these things. Even the church Mary Langston attended began to refuse Black people! So she chose not to attend any church at all.

It must have made Langston’s grandmother sad to see what had happened to her once-peaceful town. But Langston never saw her cry. And nobody ever cried in her stories. They fought, but they never cried.

Langston was thirteen when his grandmother died in 1915. And he didn’t cry—though perhaps he wanted to. Once again, his life was uprooted. His father still lived in Mexico. His mother worked in Illinois. Langston lived with friends of his grandmother’s and remained in Kansas.

But Langston managed to find happiness. Thanks to his grandmother, Langston grew up to be a proud person, too. He was happy to be Black. And he felt ready to be brave.

Chapter 2 Class Poet Langston’s grandmother had taught him to be proud of being Black. When a famous Black scientist and teacher, Booker T. Washington, came to town, they had gone to hear him speak at the University of Kansas.

Langston was given books to read by W. E. B. Du Bois, along with issues of the magazine the

Crisis, which Du Bois edited. For entertainment, Langston memorized poems by Paul Laurence Dunbar, an important Black poet. He realized the importance of education and studied hard to become a model student.

By 1916, Langston was yet again at a new school. When it came time to graduate eighth grade, he was elected class poet by his classmates. Langston had never written a poem in his life! But his teacher told him, “There’s a first time for everything.” Fourteenyearold Langston decided to try! He wrote eight stanzas, one for each of his teachers—and eight more about his classmates. (A stanza is a group of lines separated from others in a poem.)

The day of the graduation ceremony, Langston was nervous. There was a chorus onstage, along with musicians and other performers. Langston sat separate from his class, facing the audience. His palms sweated as he waited for his turn to speak. When he stood, his knees shook. Langston’s mouth went dry. But he read his poem, and everyone cheered. It was the first time Langston received applause in his entire life.

“It had never occurred to me to be a poet before, or indeed a writer of any kind,” Langston remembered. His grandmother had given him a deep love of stories and poetry, but always as a

reader. Now Langston’s dream was to be a

writer!

Langston moved once again, this time to Cleveland, Ohio, with his mother and stepbrother. He read more than ever, and soon he had several favorite poets.

He admired the musical rhythms and rhymes of Vachel Lindsay and the storytelling in poems by Edgar Lee Masters. He admired Carl Sandburg, who wrote “free verse” (poems that didn’t rhyme or have a regular rhythm).

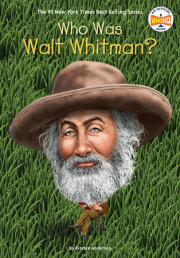

Langston’s favorite poet was Walt Whitman, who celebrated ordinary people and human experiences. Whitman’s poems were free verse, too, but with surprising rhythms all their own. They reminded Langston of how people talked at church, repeating phrases to keep his attention.

Langston noticed the student magazine at his Ohio high school hadn’t published writing by any of its Black students. He decided to submit his work. At first, his poems were rejected. But Langston didn’t give up. Eventually, the magazine staff accepted a poem. Langston had been published!

Langston didn’t notice at the time, but his earliest published poems used repetition much in the same way that Black religious folk songs, called spirituals, did. He had accidentally begun to invent his own style, which would come to incorporate other references to Black culture, including blues and work songs

Walt Whitman (1819–1892) Walt Whitman is one of America’s most important poets. He was born in New York, half a century before the Civil War and the end of slavery. He wrote poems about democracy and freedom, often using the word “I” to represent people as a collective. His poems were often about individuality and human nature.

Whitman believed all people deserved freedom and dignity, and he used his writing to celebrate the American dream. His style was expansive, with long lines and musical-sounding repetition. His major collection of poems was Leaves of Grass. It was considered controversial at the time because it rejoiced in the human body. He revised it over and over again, producing nine editions of the book in his lifetime. Just before Langston’s senior year of high school, he received a letter from his father in Mexico. He invited Langston to come live with him for the summer. Mr. Hughes was wealthy now and owned a ranch. Langston was eager to get to know the man, and to go on an adventure.

Sadly, the trip wasn’t at all what Langston had expected. And neither was his father. In Mexico, people believed Langston’s father was a dark-skinned white man, not Black at all. And Langston was forbidden from revealing the truth.

Even worse, he learned that his father

hated Black people. He called them terrible names and believed untrue ideas about them. Langston’s father offered to pay for Langston to go to college, but only if he studied to be a mine engineer and didn’t become a writer. He wanted Langston to go to Switzerland after graduation, return to Mexico for work, and leave the United States for good. It would mean giving up everything Langston wanted for his own life.

Langston had one last year of high school to think about it. By the following summer, he would have to decide which direction his life would take.

Copyright © 2024 by Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.