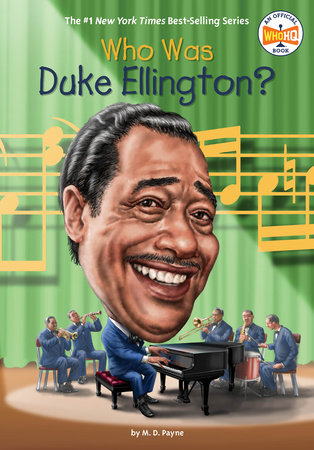

Who Was Duke Ellington?

In the summer of 1913, young Duke Ellington took a trip to Philadelphia that would change his life. He was heading to the City of Brotherly Love to hear the teenage piano master Harvey Brooks play. Duke had heard of Harvey’s piano skills earlier that summer while vacationing in Asbury Park, New Jersey, and he was curious to see Harvey play live for himself. Harvey was fourteen years old at the time (the same age as Duke), and played a musical style that had swept the United States by storm—ragtime.

Duke had heard ragtime before. In fact, almost everyone in America had—-ragtime was among the most popular musical styles in the country. But the way Harvey played the ragtime beat was different: Harvey’s style was fast and flashy. His fingers bounced with a loose oompah rhythm. His hands ran across the piano keyboard with incredible speed, as if his fingers never touched the keys. And yet, the glorious melodies seemed to roll right off the piano. It was magic. Harvey had the entire crowd in the palm of his hand—-including Duke.

When Duke got home to Washington, DC, all he wanted to do was play piano like Harvey. He practiced day and night on his family’s piano. He searched clubs, pool halls, dance halls, cafés, and bars for ragtime piano masters who could play like that. In his search, he discovered a new world. He met and studied under musicians like Doc Perry, Lester Dishman, Claude Hopkins, Gertie Wells, Sticky Mac, and Blind Johnny, among others. He listened closely, and watched how they moved their arms when they played. Duke copied their style, even how they dressed. He asked them to show him how to make that unbelievable sound.

Duke watched and learned for years on end until he was such a good player that he wrote his own music—-first just for piano, then for an entire jazz orchestra.

Once Duke started, he never stopped.

Duke, himself, became a piano master. Over a career spanning more than half a century, he wrote over three thousand songs, and told the story of African Americans in sound: protesting against the system that oppressed them and envisioning a future America filled with great hope and opportunity. Duke went on to become one of the greatest composers and musicians of the twentieth century—-an artist truly beyond category.

Chapter 1 Edward Kennedy Ellington Duke was born Edward Kennedy Ellington on April 29, 1899, to Daisy Kennedy Ellington and James Edward Ellington in Washington, DC—-the capital of the United States of America.

James Edward (or “J. E.,” as his family and friends called him) was a butler for a famous Washington doctor, and he occasionally catered parties at the White House.

Daisy was a stay--at--home mother who had given birth to one baby before Edward. That baby died soon after being born, so Daisy was extremely protective of Edward. She was always by his side.

Edward was a curious child with many interests. He spent most of his free time playing with his cousins, especially with his older cousin Sonny. Each Sunday, after Edward’s mother took them to church, he and Sonny would visit all of their aunts and uncles that lived in the city of Washington. They’d eat cake and ice cream whenever someone offered it, which was most of the time!

Edward also liked to explore the great outdoors in and around his neighborhood with friends and cousins. They would climb trees in their backyards, walk all over the city, and play in the parks they discovered. But his biggest love was baseball. When Edward was a child, baseball was a new sport. His favorite team, the Washington Senators, started playing in the American League only two years after he was born.

Another new thing in Washington, DC, in the early 1900s was the automobile. But there weren’t as many cars in Washington as in other American cities. Duke’s hometown was modern in other ways—-many homes already had electricity, and most major streets were lit with electric lights. Even so, horses were still what most people used when they didn’t want to walk or use streetcars. One reason? The president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt, preferred horses, and many people in the city wanted to be like him. Edward remembered seeing the president riding by on his horse as he and his friends played baseball.

When Edward was born, Washington had eighty--seven thousand Black residents—the largest number of any city in the U.S. Edward’s family lived in the largest Black community in Washington and the entire United States at the time: the U Street neighborhood. Edward’s neighborhood was filled with Black music and art that couldn’t be found anywhere else in the country. In fact, U Street was often called Black Broadway. The neighborhood was the center of Black culture and a symbol of stylish elegance in the city of Washington, even though the country had deep divides between Black and white cultures at the time.

Because Edward was Black, life was very different for him than for white children because of racial segregation.

Edward’s family, friends, and a strong community protected him from the worst effects of segregation. The U Street neighborhood was filled with proud Black residents, strong Black businesses, and middle--class families just like Edward’s.

Edward’s father made enough money for his family to live well. Though they weren’t rich, Edward said his dad “raised his family as though he were a millionaire.” His father had a great sense of style and manners. He wore perfectly tailored three--piece suits. He could speak with anyone he met with complete ease—-something that Edward learned to do, too.

His mother did everything to make life comfortable and happy for him. Not only did she protect and spoil him, but she also instilled a sense of pride and hope in Edward. “You are blessed,” she often told him—-so Edward believed he could do anything.

Chapter 2 A Life--Changing Sound During one of the many baseball games he played as a child, Edward was hit in the head with a baseball bat. His mother thought it was a good time for him to try something less dangerous. Edward started taking classical piano lessons. Both of his parents played piano very well. Edward often mentioned that his mother played so beautifully that it made him cry. She hoped that Edward would play piano, too, and forget all about baseball.

Edward attended the lessons, but he hated them. Everything was too stiff, too boring. Even his teacher’s name was silly: Miss Clinkscales. He barely ever practiced, and he missed recitals. He wasn’t interested in the music he was playing.

Baseball was still his favorite activity, and when Edward was in middle school, he figured out the perfect way to watch more baseball games. He got his first job selling peanuts at the stadium where the Washington Senators played. But baseball wasn’t the only sport he liked in middle school—he also started to play football and run track.

Edward was both athletic and stylish. He wore perfectly ironed button-down shirts with ties, crisp pants and suspenders, and polished shoes. His fashionable style and good manners got him his nickname. A friend called him “Duke,” and it stuck.

As middle school ended, Duke had to choose his main subject of study in high school. His parents didn’t think he had a future in sports, and Duke wasn’t interested in music. But, he always loved to draw and paint, and his parents saw he had real talent. So, he chose to study art. Duke and his family knew he could make a good living creating art for posters, signs, flyers, magazines, and newspapers.

But just after Duke turned fourteen, he and his mother spent a summer at Asbury Park on the New Jersey shore. In a time before air conditioning, going to the beach was one sure way to escape the heat. While in New Jersey, Duke worked as a dishwasher in the restaurant of a fancy hotel to earn a little extra spending money. He and the busboys talked all summer long to pass the time. They talked about sports. They talked about girls. But most of all, they talked about the sound they heard coming out of the clubs and bars: ragtime.

In 1913, listening to a piano player live was the only way most people heard ragtime music. But Duke didn’t hear any he really liked—-that is, until the headwaiter at the restaurant where Duke worked told him that he should listen to Harvey Brooks play the piano. Duke sought him out, and was immediately inspired. “After hearing him,” Duke said, “I said to myself, ‘Man, you’re just going to have to do it!’” He wanted to master the piano and play the way Harvey did.

When he returned that same year to Washington, DC, however, Duke started his art studies at the all--Black Armstrong Manual Training School. For the next few months, he would juggle art and sports at school, and his piano practice after school.

Duke also continued to work various jobs here and there, sometimes helping his dad with his catering business, sometimes working as a soda jerk (someone who served soft drinks and ice cream) at a soda fountain (a place where people came to drink sodas and eat sweets). The soda fountain also had a piano, which made the job even sweeter for Duke.

By this time, Duke just couldn’t get enough of the piano. After school, he would go to pool halls and dance halls throughout Washington—-places teenagers weren’t supposed to be!—-to learn from the piano masters.

He listened to and learned from dozens of piano masters, but he called Oliver “Doc” Perry his “piano parent.” Doc would show Duke how to play tunes in his style, and he even taught Duke how to read music. Up until that point, Duke knew how to play music only from what he heard—-a skill called playing by ear.

Doc had a very busy schedule, but he would always find time to teach Duke a few new things between his shows. Duke was an eager student—-if the melody didn’t sound right at first, he would practice over and over again until it did.

Copyright © 2020 by M. D. Payne; Illustrated by Gregory Copeland. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.