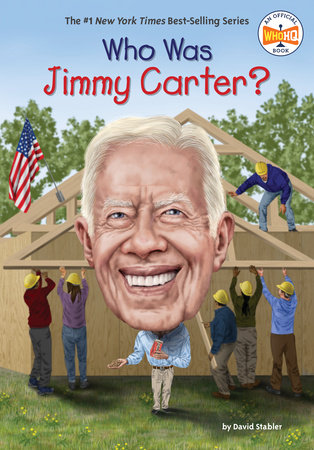

Who Is Jimmy Carter? Peanuts. At first, that’s all America knew about Jimmy Carter. He was the peanut farmer from Georgia who was running for president of the United States in 1976. And since Americans had not elected a person from the southeastern United States to the White House since Virginian Woodrow Wilson in 1916, he wasn’t given much of a chance.

In fact, Jimmy Carter was so unknown outside of Georgia, he had to introduce himself to people at his own campaign stops. “Hello, I’m Jimmy Carter, and I’m running for president,” he would say, and flash his wide grin.

Besides peanuts, the one other thing that stood out about Jimmy Carter was his smile. It quickly became the second thing people recognized about the former Georgia governor. Before long, Jimmy got the idea to combine the two things. He started using a smiling cartoon peanut as his campaign logo. Now, whenever anyone thought of peanuts or really big smiles, they thought of Jimmy Carter.

Jimmy began traveling across America in a special campaign plane he called Peanut One. He gave out bags of peanuts with his smiling face on the front. People liked his down--home image. They sensed he was a regular person, like them, and not just another politician. More importantly, they began paying attention to him.

The more they listened, the more they liked what he had to say. They learned that Jimmy Carter was more than just a peanut farmer. He was a nuclear engineer, a navy veteran, and a leader in his church. He had been a popular governor of Georgia who favored civil rights for Black Americans. He was known for being honest and straightforward with people—-and he had a plan to lead the country.

Slowly but surely, Jimmy won over those who said he could never be elected. Now, when people asked “Who is Jimmy Carter?” the answer was simple: possibly the next president of the United States.

Chapter 1: Farm Boy Home to many tiny family farms, southern Georgia has always been one of the poorest parts of the state. But the small town of Plains—-population six hundred—-was booming in 1924. That was the year James Earl Carter Jr. (who would be called Jimmy) was born, in the hospital where his mother worked as a nurse. Jimmy’s father ran the town’s general store.

When Jimmy was four years old, his family left Plains and moved to the nearby town of Archery. There his father, James Earl Carter (who went by his middle name), owned a small farm where he grew cotton, peanuts, and sugarcane. Earl and his wife, Lillian, eventually had three more children: Gloria, Ruth, and William (called Billy). While Earl was a successful farmer, the Carters were not a wealthy family by any means. They had to pump their own water from a well, had no electricity, and had to go outside to use the bathroom. The open--air “privy” was just a hole cut into a plank of wood. For toilet paper, they used old newspapers.

Farmwork kept Jimmy busy from sunup to sundown. Every day, his father paid him twenty--five cents to feed the hogs, trim the watermelon plants, and “mop the cotton”—-an especially disgusting job in which he smeared the cotton plants with a gooey bug--killing potion made from arsenic (a type of poison), molasses, and water. This homemade insecticide was so sweet--smelling that it attracted swarms of flies and honeybees, which followed Jimmy up and down the rows of cotton. By the end of a long day in the fields, Jimmy’s pants were so damp with poison that they actually stood up by themselves when he took them off.

As tough as farmwork was, Jimmy liked the money he made doing it. When he was five, he hit upon his own scheme for putting a few extra coins in his pocket. Peanuts grew in abundance on his father’s farm. Boiled peanuts were a popular snack in downtown Plains. In the afternoons, after his chores were done, Jimmy would head out into the field dragging an empty wagon behind him. He would pull handfuls of peanuts out of the ground, load them into the wagon, and take them back to the yard to wash and soak them in salted water. The next morning, he would get up extra early, boil the peanuts, and pack them into tiny bags. He took them into town and sold them for a nickel a bag. In this way, Jimmy learned the value of hard work—-and the importance of peanuts. They were two lessons he would never forget.

Life was not all farmwork for Jimmy. In elementary school, he was known as an obedient, well--behaved, and hardworking student. In the third grade, he won a class prize for reading the most books. He attended Sunday school every weekend, memorized Bible verses, and attended church services regularly. However, he got into his share of mischief as well. He once convinced his sister Gloria to bury a nickel in the ground, telling her it would grow into a money tree. When she wasn’t looking, Jimmy dug up the nickel and pocketed it for himself. Another time, Jimmy and his friends hitched one of the family billy goats, Old Gene Talmadge (named after the governor of Georgia), to a go--cart and made him pull them around the yard. On another occasion, Jimmy tried to ride the goat like a bronco, and they both ran head--on into a barbed--wire fence.

When he wasn’t working, going to school, or getting into trouble, Jimmy spent much of his time outdoors. He loved to go possum hunting with his father. He became known as one of the best tree--climbers in the town of Archery. His favorite thing to do, though, was collect arrowheads. There were thousands of them in the woods around Archery, left behind by the Native Americans who had once lived in this part of Georgia.

On rainy days when they could not work in the fields, or in winter when the fields were plowed up, Jimmy and his father would hike the land, gathering up the arrowheads. Sometimes they competed with each other to see who could find the most interesting ones. Eventually, Jimmy had a collection of about two thousand “points,” as he called them, which he always kept. It was a fun hobby, but also a reminder of how much Georgia had changed over the years since Native Americans had lived on this land.

As Jimmy would soon learn, there was another group of Americans who also had strong ties to this part of the country, and who would one day change the face of Georgia—-and the nation—-for the better.

Chapter 2: The Old South In 1929, when Jimmy was five, the US economy collapsed. It was a time that came to be known as the Great Depression. Banks were forced to close. Many stores went out of business. The population of Plains shrank from six hundred to just three hundred people. Before long, out--of--work men—-often called tramps—-began showing up at the Carters’ door. They were looking for something to eat in exchange for doing farmwork. They had heard that Jimmy’s mother was a kind woman who did not turn away strangers.

The Great Depression lasted for more than ten years. Things began to improve a bit in 1933 when a new president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, offered his “New Deal” plan to improve the economy. Jimmy’s father even worked on one of the New Deal projects, helping to bring electricity to rural towns like Plains and Archery. While the terrible economic depression did not affect the Carters as much as some of their neighbors, it did hit one community especially hard.

The town of Archery, where the Carters settled, was home to many African American families. In fact, all of Jimmy’s childhood friends were Black, including his best friends Alonzo Davis (called A.D.) and Edmund Hollis. Even though they played together almost every day, A.D. and Edmund were not treated the same as Jimmy was. They were treated worse.

Before the Civil War, Blacks in the South were held as slaves. After the Civil War ended slavery in 1865, they were treated as second--class citizens. Under the system of segregation—-also called “Jim Crow”—-Black people were separated from white people by law. Black Americans were not allowed to eat in the same restaurants, drink from the same water fountains, or go to the same schools as white Americans. The facilities reserved for Black people were never as nice as those used by whites. For a community already struggling to survive under the laws of Jim Crow, the Great Depression was a terrible blow.

In time, a civil rights movement rose up to challenge the Jim Crow system. Leaders like Rosa Parks and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. worked hard to replace the “Old South” with a “New South” of fairness and equality. But when Jimmy was a boy, Black residents who had lived in Archery all their lives were still suffering under the Old South system of segregation. When Jimmy and A.D. went to the movies together, A.D. had to buy his ticket at a different window and sit way up in the third--floor balcony, while Jimmy got to sit in a much better seat right in front of the screen.

Most white people in the South—-including Jimmy’s father—-accepted segregation laws and did not challenge them. Others, like Jimmy’s mother, Lillian, did not approve of them. She encouraged Jimmy to make friends with Black children and often invited them into the Carter home to eat in her kitchen.

Jimmy did not understand the need to separate Black people and white people. When he asked, he was simply told that this was the way it had always been. But he could not see why. Because his mother was often out of the house working as a nurse, he and his sisters were left in the care of an elderly Black woman named Rachel Clark. Jimmy came to see her as his second mother. Yet Rachel Clark’s home was not as nice as the Carters’. Even though her husband was a supervisor on Earl Carter’s farm, he still had to watch what he said around white people. He did not have the same freedoms that they did.

The pastor of Archery’s Black Methodist church, Bishop William Decker Johnson, was one of the most respected men in town. Yet when he visited the Carter farm, he had to wait outside in his car and honk the horn, because Jimmy’s father would not allow him inside the house. Nevertheless, when Bishop Johnson died in 1936, Lillian Carter took Jimmy to attend his funeral. They were two of the few white people in the church. As Jimmy looked around at the throngs of Black people celebrating Bishop Johnson’s life, he began to think that the Old South way of doing things—-and his father’s acceptance of it—-might not be the right way after all.

Copyright © 2022 by Penguin Random House LLC.. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.