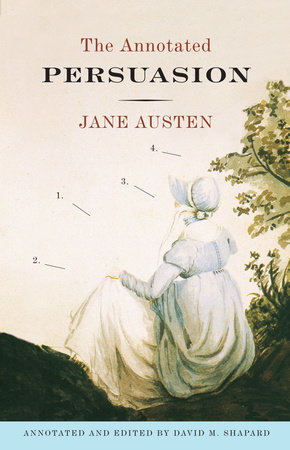

Volume One

Chapter One

Sir Walter Elliot, of Kellynch-hall, in Somersetshire (1), was a man who, for his own amusement, never took up any book but the Baronetage (2); there he found occupation for an idle hour, and consolation in a distressed one; there his faculties were roused into admiration and respect, by contemplating the limited remnant of the earliest patents; there any unwelcome sensations, arising from domestic affairs, changed naturally into pity and contempt, as he turned over the almost endless creations of the last century (3)—and there, if every other leaf were powerless, he could read his own history with an interest which never failed—this was the page at which the favourite volume always opened:

"ELLIOT OF KELLYNCH-HALL.

"Walter Elliot, born March 1, 1760, married, July 15, 1784, Elizabeth, daughter of James Stevenson, Esq. (4) of South Park, in the county of Gloucester (5); by which lady (who died 1800) he has issue Elizabeth, born June 1, 1785; Anne, born August 9, 1787; a still-born son (6), Nov. 5, 1789; Mary, born Nov. 20, 1791." (7)

Precisely such had the paragraph originally stood from the printer's hands; but Sir Walter had improved it by adding, for the information of himself and his family, these words, after the date of Mary's birth—"married, Dec. 16, 1810, Charles, son and heir of Charles Musgrove, Esq. of Uppercross, in the county of Somerset,"—and by inserting most accurately the day of the month on which he had lost his wife.

Then followed the history and rise of the ancient and respectable family, in the usual terms: how it had been first settled in Cheshire (8); how mentioned in Dugdale (9)—serving the office of High Sheriff (10), representing a borough in three successive parliaments (11), exertions of loyalty, and dignity of baronet, in the first year of Charles II., (12) with all the Marys and Elizabeths they had married (13); forming altogether two handsome duodecimo (14) pages, and concluding with the arms and motto (15): "Principal seat, Kellynch-hall, in the county of Somerset," and Sir Walter's handwriting again in this finale:

"Heir presumptive, William Walter Elliot, Esq., great grandson of the second Sir Walter." (16)

Vanity was the beginning and the end of Sir Walter Elliot's character; vanity of person (17) and of situation. He had been remarkably handsome in his youth; and, at fifty-four, was still a very fine man. Few women could think more of their personal appearance than he did; nor could the valet of any new made lord be more delighted with the place he held in society (18). He considered the blessing of beauty as inferior only to the blessing of a baronetcy; and the Sir Walter Elliot, who united these gifts, was the constant object of his warmest respect and devotion.

His good looks and his rank had one fair claim on his attachment; since to them he must have owed a wife of very superior character to any thing deserved by his own. Lady Elliot (19) had been an excellent woman, sensible and amiable (20); whose judgment and conduct, if they might be pardoned the youthful infatuation which made her Lady Elliot, had never required indulgence afterwards.—She had humoured, or softened, or concealed his failings, and promoted his real respectability for seventeen years; and though not the very happiest being in the world herself, had found enough in her duties (21), her friends, and her children, to attach her to life, and make it no matter of indifference to her when she was called on to quit them.—Three girls, the two eldest sixteen and fourteen, was an awful (22) legacy for a mother to bequeath; an awful charge rather, to confide to the authority and guidance of a conceited, silly father. She had, however, one very intimate friend, a sensible, deserving woman, who had been brought, by strong attachment to herself, to settle close by her, in the village of Kellynch; and on her kindness and advice, Lady Elliot mainly relied for the best help and maintenance of the good principles and instruction which she had been anxiously giving her daughters. (23)

This friend, and Sir Walter, did not marry, whatever might have been anticipated on that head by their acquaintance.—Thirteen years had passed away since Lady Elliot's death, and they were still near neighbours and intimate friends; and one remained a widower, the other a widow.

That Lady Russell (24), of steady age and character, and extremely well provided for, should have no thought of a second marriage, needs no apology to the public, which is rather apt to be unreasonably discontented when a woman does marry again, than when she does not; (25) but Sir Walter's continuing in singleness requires explanation.—Be it known then, that Sir Walter, like a good father, (having met with one or two private disappointments in very unreasonable applications) prided himself on remaining single for his dear daughter's (26) sake. For one daughter, his eldest, he would really have given up any thing, which he had not been very much tempted to do. Elizabeth had succeeded, at sixteen, to all that was possible, of her mother's rights and consequence; and being very handsome, and very like himself, her influence had always been great, and they had gone on together most happily. His two other children were of very inferior value. Mary had acquired a little artificial importance, by becoming Mrs. Charles Musgrove; but Anne, with an elegance of mind and sweetness of character, which must have placed her high with any people of real understanding, was nobody with either father or sister: her word had no weight; her convenience was always to give way;—she was only Anne.

To Lady Russell, indeed, she was a most dear and highly valued god-daughter, favourite, and friend. Lady Russell loved them all; but it was only in Anne that she could fancy the mother to revive again.

A few years before, Anne Elliot had been a very pretty girl, but her bloom (27) had vanished early; and as even in its height, her father had found little to admire in her, (so totally different were her delicate features and mild dark eyes from his own); there could be nothing in them now that she was faded and thin, to excite his esteem. He had never indulged much hope, he had now none, of ever reading her name in any other page of his favourite work. All equality of alliance (28) must rest with Elizabeth; for Mary had merely connected herself with an old country family of respectability and large fortune (29), and had therefore given all the honour, and received none: Elizabeth would, one day or other, marry suitably.

It sometimes happens, that a woman is handsomer (30) at twenty-nine than she was ten years before; and, generally speaking, if there has been neither ill health nor anxiety, it is a time of life at which scarcely any charm is lost. It was so with Elizabeth; still the same handsome Miss Elliot that she had begun to be thirteen years ago; and Sir Walter might be excused, therefore, in forgetting her age, or, at least, be deemed only half a fool, for thinking himself and Elizabeth as blooming as ever, amidst the wreck of the good looks of every body else; for he could plainly see how old all the rest of his family and acquaintance were growing. Anne haggard, Mary coarse, every face in the neighbourhood worsting; (31) and the rapid increase of the crow's foot about Lady Russell's temples had long been a distress to him.

Elizabeth did not quite equal her father in personal contentment. Thirteen years had seen her mistress of Kellynch Hall, (32) presiding and directing with a self-possession and decision (33) which could never have given the idea of her being younger than she was. For thirteen years had she been doing the honours, and laying down the domestic law at home, and leading the way to the chaise and four (34), and walking immediately after Lady Russell out of all the drawing-rooms and dining-rooms in the country (35). Thirteen winters' revolving frosts had seen her opening every ball of credit which a scanty neighbourhood afforded (36); and thirteen springs shewn their blossoms, as she travelled up to London with her father (37), for a few weeks annual enjoyment of the great world (38). She had the remembrance of all this; she had the consciousness of being nine-and-twenty, to give her some regrets and some apprehensions. She was fully satisfied of being still quite as handsome as ever; but she felt her approach to the years of danger (39), and would have rejoiced to be certain of being properly solicited by baronet-blood within the next twelvemonth or two. Then might she again take up the book of books with as much enjoyment as in her early youth; but now she liked it not. Always to be presented with the date of her own birth, and see no marriage follow but that of a youngest sister (40), made the book an evil; and more than once, when her father had left it open on the table near her, had she closed it, with averted eyes, and pushed it away.

She had had a disappointment, moreover, which that book, and especially the history of her own family, must ever present the remembrance of. The heir presumptive, the very William Walter Elliot, Esq. whose rights had been so generously supported by her father, had disappointed her.

She had, while a very young girl, as soon as she had known him to be, in the event of her having no brother, the future baronet, meant to marry him; and her father had always meant that she should. He had not been known to them as a boy, but soon after Lady Elliot's death Sir Walter had sought the acquaintance, and though his overtures had not been met with any warmth, he had persevered in seeking it, making allowance for the modest drawing back of youth; and in one of their spring excursions to London, when Elizabeth was in her first bloom, Mr. Elliot had been forced into the introduction.

He was at that time a very young man, just engaged in the study of the law (41); and Elizabeth found him extremely agreeable, and every plan in his favour was confirmed. He was invited to Kellynch-Hall; he was talked of and expected all the rest of the year; but he never came. The following spring he was seen again in town (42), found equally agreeable, again encouraged, invited and expected, and again he did not come; and the next tidings were that he was married. Instead of pushing his fortune in the line marked out for the heir of the house of Elliot, he had purchased independence (43) by uniting himself to a rich woman of inferior birth (44).

Sir Walter had resented it. As the head of the house (45), he felt that he ought to have been consulted, especially after taking the young man so publicly by the hand: "For they must have been seen together," he observed, "once at Tattersal's (46), and twice in the lobby of the House of Commons." (47) His disapprobation was expressed, but apparently very little regarded. Mr. Elliot had attempted no apology, and shewn himself as unsolicitous of being longer noticed by the family, as Sir Walter considered him unworthy of it: all acquaintance between them had ceased.

This very awkward history of Mr. Elliot, was still, after an interval of several years, felt with anger by Elizabeth, who had liked the man for himself, and still more for being her father's heir, and whose strong family pride could see only in him, a proper match for Sir Walter Elliot's eldest daughter. There was not a baronet from A to Z, whom her feelings could have so willingly acknowledged as an equal. Yet so miserably had he conducted himself, that though she was at this present time, (the summer of 1814,) wearing black ribbons for his wife (48), she could not admit him to be worth thinking of again (49). The disgrace of his first marriage might, perhaps, as there was no reason to suppose it perpetuated by offspring, have been got over, had he not done worse; but he had, as by the accustomary intervention of kind friends they had been informed, spoken most disrespectfully of them all (50), most slightingly and contemptuously of the very blood he belonged to, and the honours which were hereafter to be his own. This could not be pardoned.

Such were Elizabeth Elliot's sentiments and sensations; such the cares to alloy, the agitations to vary, the sameness and the elegance, the prosperity and the nothingness, of her scene of life-such the feelings to give interest to a long, uneventful residence in one country circle, to fill the vacancies which there were no habits of utility abroad, no talents or accomplishments for home, to occupy (51).

But now, another occupation and solicitude of mind was beginning to be added to these. Her father was growing distressed for money. She knew, that when he now took up the Baronetage, it was to drive the heavy bills of his tradespeople (52), and the unwelcome hints of Mr. Shepherd, his agent (53), from his thoughts. The Kellynch property was good, but not equal to Sir Walter's apprehension of the state (54) required in its possessor (55). While Lady Elliot lived, there had been method, moderation, and economy, which had just kept him within his income; but with her had died all such right-mindedness, and from that period he had been constantly exceeding it. It had not been possible for him to spend less; he had done nothing but what Sir Walter Elliot was imperiously called on to do; but blameless as he was, he was not only growing dreadfully in debt (56), but was hearing of it so often, that it became vain to attempt concealing it longer, even partially, from his daughter (57). He had given her some hints of it the last spring in town; he had gone so far even as to say, "Can we retrench? does it occur to you that there is any one article in which we can retrench?"—and Elizabeth, to do her justice, had, in the first ardour of female alarm, set seriously to think what could be done, and had finally proposed these two branches of economy: to cut off some unnecessary charities (58), and to refrain from new-furnishing the drawing-room; to which expedients she afterwards added the happy thought of their taking no present down to Anne, as had been the usual yearly custom (59). But these measures, however good in themselves, were insufficient for the real extent of the evil, the whole of which Sir Walter found himself obliged to confess to her soon afterwards. Elizabeth had nothing to propose of deeper efficacy. She felt herself ill-used and unfortunate, as did her father; and they were neither of them able to devise any means of lessening their expenses without compromising their dignity, or relinquishing their comforts in a way not to be borne.

There was only a small part of his estate that Sir Walter could dispose of; but had every acre been alienable (60), it would have made no difference. He had condescended (61) to mortgage as far as he had the power (62), but he would never condescend to sell (63). No; he would never disgrace his name so far. The Kellynch estate should be transmitted whole and entire, as he had received it (64).

1. Somersetshire: A county in southwestern England.

2. The baronetage is a book listing baronets. Baronets are hereditary knights: both baronets and knights are called "Sir," but baronets pass down their title to a descendant; for this reason they are more prestigious. Various baronetages were published, including ones in 1804 and 1808 with entries similar to that here and in a duodecimo format (see note 14 below).

3. The book listed families in order of receipt of the title. Thus Sir Walter would first see the earliest patents (i.e., grants conferring the baronetcy); there would be only a "limited remnant" of them because most early baronetcies had expired by this point due to the death of all possible heirs. Sir Walter could only know this by consulting another book such as Dugdale (see note 9 below) and comparing its list of all baronetcies with the entries in his baronetage, for the latter would show only existing titles-that he has done this indicates how obsessed he is with the matter. This carefully acquired knowledge arouses Sir Walter to admiration for himself as the holder of a surviving baronetcy. He would later come to the many pages showing the creations, or new titles, of the last (i.e., eighteenth) century and feel contempt for their relative newness (his came from 1660; see note 12 below).

4. Esq.: Esquire. This was an informal title, often given to gentlemen, especially prominent landowners, who had no other title. It derives from the medieval term "squire," one who served a knight (knight being the lowest of the formal titles).

5. Gloucester: a county to the immediate northeast of Somerset.

6. Stillborn children were not unusual then. Jane Austen mentions one in a letter, and not as a remarkable event (Oct. 27, 1798).

7. This entry is very similar to ones in actual baronetages of the time, albeit with slight differences in the wording and the exact information included (Jane Austen may have been recalling a book she had seen years earlier). A history of the current baronet begins each family entry; similar histories of all preceding baronets, starting from the oldest, comprise the rest of the entry.

8. Cheshire: a county farther north from Somerset (see map, p. 000).

9. Sir William Dugdale had in 1682 published The Antient Usage in Bearing of such Ensigns of Honour as are commonly call'd Arms. It included lists of those holding various titles and honors, including baronets.

10. The High Sheriff (often simply called sheriff) was, after the Lord Lieutenant, the leading official in a county, responsible for the execution of the laws. He served for one year. The position, usually held by a member of the gentry, carried great prestige and would be a source of family pride.

11. Representing a borough, the main unit sending representatives to Parliament, would be an even greater source of pride. Successive parliaments meant consecutive sessions; members often changed from one session to another, so serving for three in a row would be a further distinction.

12. This means the Elliot family sided with the monarchy during the English Civil War and was later rewarded with a baronetcy. The civil war was a struggle between the king and parliament in the 1640s that ended with the execution of Charles I; in 1660 his son Charles II returned and restored the monarchy. More baronetcies were created in the first year of his reign than in any other year, as the monarchy had many loyal supporters to reward.

13. Mary and Elizabeth were traditionally two of the most popular female names in England. The strong family traditions that kept them popular is shown in their being used again in this generation, with the eldest daughter given the mother's name of Elizabeth, a common procedure.

14. duodecimo: book in a small format; see note 7, for more on book sizes.

15. At the end of each entry the family arms and crest would be listed, along with (in most cases) the family motto, and (in some cases) the family seal.

16. The exact relationship of William Elliot and Sir Walter is never specified. If William's father was of the same generation as Sir Walter, he would be a first cousin, and William a second cousin. William Elliot's name probably came from his father, with his middle name being in honor of the baronetcy (in most cases each successive baronet had the same first name). He is the heir presumptive because the baronetcy cannot be inherited by a woman; in the absence of a son, it goes to the male relative next in line. This was also usually the case with landed estates, and later it is revealed that William Elliot is indeed the expected heir of Sir Walter's estate.

17. person: personal appearance.

18. A new made lord was someone who had just been raised by the king to the nobility, or peerage; this position, higher than a baronet, gave the possessor the right to sit in the House of Lords. It was an exclusive honor, enjoyed by fewer than three hundred men at this time. A valet was a male servant who took care of his master's clothing and grooming, and often accompanied him wherever he went. Servants frequently identified with their employers, and the nature of a valet's position, along with the high rank among servants he enjoyed, made him especially prone to this. Since servants' social status rose with that of their employers, a valet whose master was recently ennobled would have even more reason to be delighted with his position.

19. The wife of a baronet was called "Lady + last name." Only women from the upper ranks of the nobility used both first and last name after "Lady."

20. amiable: kind, friendly, good-natured. The word then suggested general goodness, not just outward agreeableness.

21. Her duties, as the wife of a baronet, would have centered around managing the household, which included purchasing what was needed, keeping the household budget, planning meals, and, most of all, supervising the servants and their various labors. It was generally expected that men would allow their wives to take charge of these matters, without substantial interference—the mistress of the house is referred to as "laying down the domestic law at home." Other duties of such a mistress would have been entertaining guests, attending church regularly, and performing charitable acts in the neighborhood.

22. awful: impressive, solemn; worthy of awe and respect.

23. This may refer to formal instruction as well as to general maternal guidance; young children, and girls in later years, were frequently educated at home, either by a governess or their mother. It is soon revealed that Anne went away to school, probably for the first time, after her mother's death.

24. Lady Russell is the widow of a knight, a rank just below baronet. As with Lady Elliot, this means she uses just her last name with "Lady."

25. Widows who remarried were often subject to disapproval. One reason was that a woman, on marrying, was considered a permanent part of her husband's family. Remarriage would mean abandoning that family for another, which could be regarded as a betrayal, especially if the woman was able to take property with her into the new marriage. Remarriage was also condemned as an indulgence in lust improper in women, who were expected to be chaste, or as a violation of the undivided and permanent love a woman was supposed to feel for her husband. In a letter Jane Austen seems to give voice to this last sentiment when, commenting on a woman who remarried, she writes, "had her first marriage been of affection . . . I should not have forgiven her" (Dec. 27, 1808). At the same time, she explains that, in this case, she believes the woman justified in remarrying, and the wording here suggests she regards this condemnation of widows as unfair.

26. daughter's: It may be that the apostrophe was wrongly placed in the original printing, as happened with punctuation marks in the initial editions of Jane Austen's works, and that this is supposed to be daughters.' Later Elizabeth, speaking to Anne, says that their father has "kept himself single so long for our sakes" (emphasis added). While Sir Walter does care truly only for Elizabeth, he would probably not pride himself on such flagrant partiality, just as Elizabeth would not claim to be its beneficiary.

27. bloom: prime of beauty, state of greatest loveliness. The word is frequently used in Jane Austen in this sense, applied particularly to young women in their freshest looks. A contemporary book on beauty (The Mirror of Graces, 1811) gives a sense of the origins of the term by comparing, in a chapter discussing how best to preserve "the bloom of beauty," the progression of a woman's appearance both to the progression of the seasons, with spring first and winter last, and to the blossoming and ultimate fading and death of a flower. One reason for particular concern about bloom in this period was that facial cosmetics, which might help disguise the effects of age, had become generally frowned upon-see note 34.

28. alliance: marriage. The term connoted especially the union of different families through marriage, which was often a central purpose of marriage.

29. An old country family is one that had long been prominent in this country, i.e., county. Such antiquity would be a mark of additional distinction, though it still would not make a family rank as high as one with a baronetcy.

30. "Handsome" was often used to describe women at this time. It had no suggestion of masculine appearance.

31. worsting: growing worse, deteriorating.

32. After her mother died Elizabeth, as the eldest daughter, and already sixteen at that point, would have assumed her place as mistress of the house; see note 21, for a description of a mistress's duties.

33. decision: determination, firmness.

34. chaise and four: a chaise was a type of carriage; "four" refers to the number of horses driving it. The chaise, from the French word for "chair," was one of the most popular carriages of the time, used especially for long-distance transportation. It was a small enclosed carriage with one seat, which could accommodate three people facing forward (in contrast to the coach, which had two seats facing each other). The Elliots need only a chaise since there are only three family members living there; it would also be useful for Sir Walter and Elizabeth's journeys to London. Chaises could use only two horses, but four would make for a faster journey and be a sign of distinction, while also costing more. The conflict of distinction and expense on this very point will shortly arise (see note 12).

35. They would proceed according to rules of precedence, which were especially in force at formal dinner parties: usually everyone would gather in the drawing room, and then go into the dining room in order of rank; afterward the ladies, also in order, would return to the drawing room. Lady Russell precedes Elizabeth because, even though her husband ranked below Sir Walter, she was his wife and Elizabeth is only the daughter of Sir Walter. Elizabeth precedes Anne because she is the eldest sister (for more, see note 31).

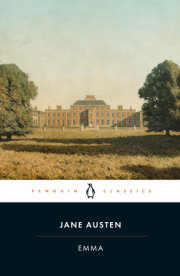

36. To open a ball is to be part of the lead couple in the first dance. It would be an honor normally enjoyed by the unmarried gentleman and lady of highest rank, which would always be Elizabeth in this neighborhood. A ball of credit would be a formal ball attended by people of good families. Such balls would be especially likely to occur in the winter in the country, when outdoor amusements were less available. Pride and Prejudice and Mansfield Park depict elaborate country balls in, respectively, November and December.

37. Spring was the time of the London season, to which the aristocracy and many country gentry would flock for a variety of social events and amusements.

38. great world: the world of the highest-ranking people in society.

39. These are the years when a woman lost her marital eligibility. This happened early in this society (see note 27). For many women twenty-nine would already be in those years; Elizabeth's beauty and birth have extended her eligibility a little.

40. Because of the importance of marriage for women in this society—it was considered a woman's natural destiny and duty, and it was usually the only way she could achieve wealth, influence, and high status—there was a strong belief that sisters should ideally marry in order of birth. Some families, if an older daughter had not married, would even delay letting their younger daughters "come out," socialize freely with eligible young men; the delay would keep the younger girls from competing with the eldest. This could lead to rivalry between sisters as well: in a youthful satire, "Three Sisters," Jane Austen depicts a woman who marries a man she does not like out of fear that, if she does not, one of her younger sisters will marry him. Hence, for Elizabeth it is a further pain and humiliation that she, the eldest, is preceded in marriage by her youngest sister.

41. Mr. Elliot would have been studying to become a barrister, the branch of the law considered genteel. For what this study involved, see note 32.

42. town: London.

43. independence: financial independence.

44. For this woman's history, and its significance as an example of social climbing in this society, see note 45.

45. He sees himself as head of the house, or family, because he is the one Elliot who has a title.

46. Tattersal's, or Tattersalls in more recent spelling, was the main place in London for buying and selling horses. Horses were a particular concern of gentlemen, who would use them for their carriages, for riding, and for hunting, and who in consequence often owned several. All this made Tattersalls a popular venue for upper-class men. For a picture of Tattersalls, giving a sense of its clientele, see the following page.

47. The House of Commons is the lower, though also the more powerful, of the two houses of Parliament. It was dominated then by country gentry like Sir Walter. While he himself does not appear to have a seat, he probably has friends who do, and he would see it as a natural place to meet other men of his class and to introduce his heir to them.

48. Mourning attire was a universal practice among the more affluent classes at this time, with an elaborate etiquette indicating what was worn and for how long. The ribbons worn by Elizabeth represent a bare minimum: full mourning for women included black gowns as well as other articles, and such mourning was often adopted for people no closer than cousins. Since Mrs. Elliot has just died—in a conversation in the following February Anne says she has "not been dead much above half a year"—the limited mourning adopted here suggests the estrangement of Sir Walter and his children from Mr. Elliot.

49. There was no prohibition against marriage between cousins; see note 9.

50. Their hearing this gossip from friends, whether truly kind or not, suggests the relatively small upper-class society of this time, something indicated at other places in Jane Austen. There were only around six hundred baronetcies in all of England at this time, along with almost three hundred noble families of higher rank.

51. Upper-class women had a great deal of leisure time, even if, like Elizabeth, they had the duties of a mistress of the house. This would be especially true if they had no children. The "habits of utility abroad" (i.e., outside the house) probably refers to charitable activities: assisting and visiting the local poor was considered an important activity for elite ladies, though, as Elizabeth shows, not all did it. Talents and accomplishments included music, drawing, and various decorative activities such as embroidery: these were taught to girls, and young women were encouraged to continue cultivating them. One argument made in favor of such continued cultivation was that these activities—along with reading, another pastime later shown to be of no interest to Elizabeth—helped fill ladies' leisure hours in productive ways.

52. His tradespeople would be the merchants he bought from. It was standard commercial practice then to sell items by credit, especially when dealing with wealthy customers, and then send them periodic bills.

53. Mr. Shepherd is a lawyer who manages Sir Walter's affairs; see note 1.

54. state: dignity, pomp, grandeur.

55. It was commonly believed that those of high status should demonstrate and support that status by external display. This would mean both expensive and impressive possessions—houses, furnishings, clothes, carriages, horses—and a general willingness to spend money freely. Those who did not could lose prestige, while also seeing themselves outdone by others of their rank. Thus Sir Walter has a powerful social reinforcement for his natural extravagance.

56. Many wealthy landowners fell into debt. This had long been the case, and it may have become more common during the half century preceding this novel, despite rising incomes from agriculture. The principal cause was excessive expenditure. Maintaining a large country house, with its attendant army of servants, was itself an enormous expense, and in the eighteenth century many owners—spurred by changes in tastes, desire for greater comfort, or simple competitive emulation—undertook the additional expense, potentially enormous, of improving or even completely rebuilding the house and installing new elaborate landscaping as well. Increasing numbers of wealthy people also added to their expenses by living for substantial parts of the year in London, which had been growing tremendously in size and in the opportunities for enjoyment it offered, and which was increasingly accessible thanks to improvements in the speed and ease of travel. To all these pressures and temptations were added a relaxed attitude to debt among much of the elite and a willingness among many people to lend to those of high status.

57. It is notable that Sir Walter thinks only of informing and consulting Elizabeth.

58. Charity then was a basic function of the upper classes, especially if they were prominent landowners. In a letter Jane Austen writes of the standard Christmas duty of "laying out Edward's money for the poor"—Edward was a brother of hers who had inherited a wealthy estate. Hence even someone as selfish as Sir Walter has regular charities he contributes to, and even when Elizabeth selects their charities as prime candidates for elimination, a sign of her similar selfishness, she does not propose eliminating them all.

59. London offered a great variety of shops, so it would be natural for those visiting it to buy gifts for those who remained in the country.

60. alienable: capable of being transferred to another's ownership.

61. condescend: lower himself.

62. Sir Walter's estate, like most estates of the time, was governed by a system of strict settlement, under which the current owner was only a life tenant who received the current income from the property but was bound to hand it intact to the next holder, his heir. The central purpose of the system was to preserve family property through the generations, which meant, among other things, keeping profligate or foolish owners like Sir Walter from selling to pay off debts. In many cases, as is true here, a small portion of the estate was granted outright to the current owner to give him some flexibility to deal with unexpected problems; this is what Sir Walter could dispose of or sell if he wished.

63. Mortgaging was a standard way for landowners to raise money, whether for paying debts or for other purposes. Sir Walter has been able to mortgage only the small part of the estate under his control; the strict settlement would block him from mortgaging the rest.

64. Sir Walter's strong scruples, and fear of disgracing his name, stem from the powerful emphasis in upper-class society on preserving family tradition and family social position through the generations. Sir Walter's own obsession with his ancestry shows how much he shares this ethos. Someone who failed to pass on his inheritance intact would be regarded as having violated one of the most basic of his duties, to his family and to society as a whole (since an elite landowning class with strong traditions and strong ties to its land was considered an essential source of political and social leadership and stability).

Copyright © 2010 by Jane Austen, Annotations by David M. Shapard. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.