CHAPTER ONE

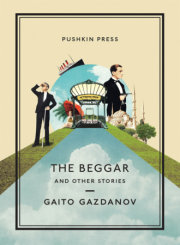

On the morning of 20th September 1928,

between nine and ten, three events occurred

that set the stage for this tale. Alexei Ivanovich Shaibin,

one of its many heroes, turned up at the Gorbatovs’;

Vasya, the Gorbatov son, off spring of Stepan

Vasilievich and Vera Kirillovna and stepbrother of

Ilya Stepanovich, received a letter from Paris, from his

friend Adolf Kellerman, with important news about

Vasya’s father; and fi nally, a poor wayfarer and his

guide arrived at the Gorbatovs’ farm in a broad valley

of the Vaucluse.

No one knew this man’s name. Who was he? What

road had led him to his present wanderings? He had

passed through here the previous year, in the spring,

and he was already known in the surrounding area; at

that time he was still sighted and walked alone, an old

Astrakhan cap pulled to his eyes, sending up white

dust and bowing to those he met. He had spoken with

Ilya and with Vera Kirillovna herself for a long time;

he’d drunk, had dinner, and spent the night. But

neither Vasya nor his sister Marianna saw the wayfarer

the next morning. He had left at dawn, blessing the

house, the orchard, and the cowshed where the oxen

slept, and the attic where Ilya slept. Later, people said

he’d gone west, but more likely he’d gone southwest,

past Toulouse, to see the Cossacks who had settled in

those parts.

Now he was blind, and that same Astrakhan cap

had slipped over his shaggy eyebrows. A dark blue scar

ran across his face, and he had no beard growing on

his cheeks; you could tell a regimental doctor had once

mended his face in haste, slapping together the torn

pieces of his no longer young, swarthy skin. He was

tall and ominously thin, and his military trousers

sported red patches in many places—possibly scraps

from someone else’s service trousers, but French, trousers

that had once known the defense of Verdun. The

wayfarer walked with his harsh withered hand resting

on the shoulder of his guide, a black-eyed girl of about

twelve whose name was Anyuta.

They stopped at the gate and the old man took off

his cap. The girl looked over the low stone wall. There

she saw an orchard, a vegetable plot, and a house with

outbuildings partially hidden by stocky willows. In the

silence and cool of the morning, the house stood low,

burned by the sun over the long summer, with a northfacing

porch and squat asparagus shoots, while farther

away, past the dark blue shadow of moribund cypresses,

plowed fi elds spread out, ready for winter crops.

This was a human habitation created not in

struggle with nature but at one with it. The sun was

already high in the untroubled sky, and birds fl ew

swiftly in its gleam, like short, darting needles sewing

through it.

Vasya and Marianna went over to the gate, even

though they were up to their ears in work; they pushed

back their round straw hats, which were as hard as tin,

and their hands were covered in dirt.

“You could have sung something,” Marianna said.

“Where have you come from?” She began examining

Anyuta, her long colorful skirt and the narrow ribbon

tied around her head.

The wayfarer made a low, unhurried bow.

“From the Dordogne, gentle lady,” he said. “We

are on our way south, from the Dordogne to the

Siagne River, to hot climes, to see good people, and in

the spring back to our own people, for the summer.

And there—God will provide. People know us.”

Vasya came closer, his face bathed in sweat.

“But what are you going there for?” he asked.

Anyuta gave him a frightened look. Her heart

started pounding for fear they would have to leave

without seeing the person they’d come to see, for the

sake of whom they’d made a detour from the highway,

past the river and mill. How can these people ask!

How dare they! she thought.

“We walk, my dear boy,” the wayfarer replied,

“because we’re too old and blind to work. We go to

good people’s homes to eat and have conversations

with good people, and we do not complain of our

Lord God.”

Marianna shrugged lightly and grinned.

“Why do you speak so oddly? We were told you

were an educated man, or else a priest.”

Anyuta rushed to the old man in despair.

“Granddad, can we go? Granddad?” she whispered,

tugging on his sleeve. “Let’s go, dear Granddad.

We can come some other time!”

The beggar put his hand on her shoulder but did

not go where she was pulling him. He took two steps

toward the wall, making a deep rut in the road dust

with his staff .

“They told you wrong, my good lady,” he replied,

and his micaceous eyes fl ashed. “I am no priest. Nor

was I a doctor or an engineer. Allow us to sit on your

little porch. I know in your part of the world porches

always look into the shade, and if Vera Kirillovna can

fi nd a little water for us, Anyuta and I would be very

grateful.”

And he bowed abruptly at the waist.

Marianna opened the gate, and the wayfarer

passed between her and Vasya, Anyuta leading him.

He walked majestically, without that grim fussiness so

often characteristic of the blind. They passed slowly

between the vegetable beds toward the house; from

time to time the beggar lifted his right hand from

Anyuta’s thin shoulder and made a fl uid cross over the

beds, and the house, and the bent pear trees’ smeared

trunks. A sack hung motionlessly from his shoulder;

the sack was military, like his trousers. No one knew

this man’s name.

Marianna watched him go, grinned again, and

leaned over the shoots poking out of the earth.

“Come on, let’s go, let’s listen,” Vasya said, “or

does nothing have anything to do with you anymore?”

He wiped his wet face with his sleeve and looked at

her expectantly.

“No, it doesn’t,” Marianna replied reluctantly.

“There’s nothing for me to hear. But you go on.”

Something stirred in Vasya’s sleepy face; his gaze

slid down Marianna’s back, her black gathered skirt,

her wooden shoes.

“I’ve just had a letter from Adolf,” he said sullenly.

“Has that nothing to do with you?”

Marianna turned her merry, high-cheekboned face

toward him.

“You mean he’s summoning you?”

“Yes. He writes about Father. Old Kellerman has

come and wants a meeting with me. Father’s been

found, and he has an important post.”

Marianna clapped her hands and gave her brother

a frightened look.

“Ah, that Gorbatov!” she exclaimed. “He lets us

know through Kellerman. He wants to lure you there!”

Vasya sat down beside her and put an arm around

his knees.

“It’s time for me to go,” he said fi rmly. “Father is

calling, demanding that at least one of us return. At

fi rst old Kellerman was going to demand Adolf get

Ilya, but Adolf told him fl at out that was impossible.

Whereas I . . . I’ve been wanting to go there for a

whole year, and Adolf has summoned me. He writes

that my papers can be in order in two days.”

“A whole year!” Marianna said slowly.

“I never tried to pretend otherwise. Mama knows

it, and so does Ilya. I just can’t here. My path takes me

home, to Father, and this is the goal Kellerman and I

share.” He dropped his head. “I know that Kellerman

is trying to get in Father’s good graces, but does that

matter, Marianna? I might have gone even without

this.”

“No, you wouldn’t!”

“I don’t know. It’s impossible for me here. Father’s

working with Kellerman there and despises our settling

here. I’m going. I’ll have money, I’ll have the life I

want. I didn’t choose this one. And you know, it’s

essential to me—I mean, roots are absolutely

essential.”

“Ilya says we should have roots in the air.”

“Ilya’s always going to say something you don’t

know how to answer. But there, Father’s a big shot. He

sent Kellerman to Paris on business and he’s going

back in a month. You have to understand. I’ve been

waiting a whole year for this, waiting for Gorbatov to

turn up and summon me. Adolf has worn me down!”

“He’s the one who won you over, and he’s the one

sending you after your roots. He’s a scoundrel, your

Adolf, and Gorbatov’s a fi ne one! To lure you away, to

tempt you . . . Oh, Vasya, dear Vasya, what an automaton

you are, my God! If I were Ilya I would lock you

in the attic and go to Paris myself and demand that

Kellerman back off . If they don’t leave you in peace—

someone should lodge a complaint. There’s manure to

shovel here and you’re leaving!”

Copyright © 2021 by Nina Berberova. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.