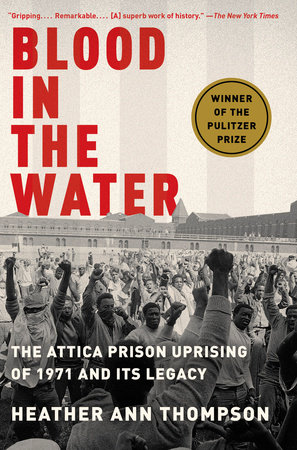

IntroductionState SecretsOne might well wonder why it has taken forty-five years for a comprehensive history of the Attica prison uprising of 1971 to be written. The answer is simple: the most important details of this story have been deliberately kept from the public. Literally thousands of boxes of documents relating to these events are sealed or next to impossible to access.

Some of these materials, such as scores of boxes related to the McKay Commission inquiry into Attica, were deemed off limits four decades ago—in this case at the request of the commission members who feared that state prosecutors would try to use the information to make cases against prisoners in a court of law. Other materials related to the Attica uprising, such as the last two volumes of the Meyer Report of 1976, were also sealed back in the 1970s. Members of law enforcement fought hard to prevent disclosure of this report in particular. Although a judge has recently ruled that these volumes can now be released to the public, the redaction process that they first will undergo means that crucial parts of Attica’s history will almost certainly remain hidden.

The vast majority of Attica’s records, however, are not sealed, and yet they might as well be. Federal agencies such as the FBI and the Justice Department have important Attica files, for example, but when one requests them via the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), they have been rendered nearly unreadable from all of the redactions. And then there are the records held by the state of New York itself—countless boxes housed in various upstate warehouses that came from numerous sources: the state’s official investigation into whether criminal acts had been committed at Attica during the rebellion, its five years of prosecuting such alleged crimes, and its nearly three decades of defending itself against civil actions filed by prisoners and hostages. In 2006 I was able to get an index of these files, which made clear that this is a treasure trove of Attica documentation: autopsies, ballistics reports, trooper statements, depositions, and more. It constitutes ground zero of the Attica story.

Everything that the state holds in these warehouses can also be requested via FOIA, but here as well it is difficult to get documents released. As this book goes to press, and after waiting since 2013 for some explanation of whether my latest FOIA request would net me important documents, I just received word that state officials will not be giving me those materials. I know the items that I requested are there, according to the state’s own inventory, and I also know that I did not ask for any grand jury materials that would be protected, and yet my request is still being denied.

But thanks to so many who lived and litigated the Attica uprising, as well as so many others who took the time to chronicle or to collect parts of this history in newspapers, in memoirs, and in archives outside the control of the state of New York, I was still able to rescue and recount the story of Attica.

And, because of two extraordinarily lucky breaks I had while I was trying to write this book, the history you are about to read is one that state officials very much hoped would not be told.

First, in 2006 I stumbled upon a cache of Attica documents at the Erie County courthouse in Buffalo, New York, that changed everything. I had, for two years, been calling and writing every county courthouse and coroner’s office and municipal building in upstate New York in order to find any Attica-related records that had not been placed under lock and key by the Office of the Attorney General or sealed by a judge. I had little to go on in these early years—I didn’t have case numbers to search, I knew few names to inquire about. But one day I hit pay dirt. I was on the phone with a woman from the Erie County courthouse who thought that a bunch of Attica papers had recently been placed in the back room there. They had been somewhere else, but had been moved to the Office of the Clerk, perhaps after suffering some water damage. I headed to Buffalo.

When I walked into that dim file room at the courthouse I was taken aback. In front of me, in complete disarray on floor-to-ceiling metal shelves, were literally thousands of pages of Attica documents. In this mess was everything from grand jury testimony, to depositions and indictments, to memos and personal letters. Most stunningly, though, I found in this mountain of moldy papers vital information from the very heart of the state’s own investigation into whether crimes had been committed during the rebellion or the retaking of the prison. In short, I had found a great deal of what the state knew, and when it knew it—not the least of which was what evidence it thought it had against members of law enforcement who were never indicted. I took as many notes as I could take, and Xeroxed as many pages as they would let me, and, finally, had much of what I needed to write a history of Attica that no one yet knew.

Then, in 2011, I had another incredibly lucky break. I had just published an op-ed in

The New York Times on the occasion of Attica’s fortieth anniversary when I received an email from Craig Williams, an archivist at the New York State Museum who wanted help making sense of a new trove of materials he had received from the New York State Police. Troopers had just turned over an entire Quonset hut full of items they had gathered from the prison yards of Attica immediately after the four-day standoff there in 1971—items that the state considered evidence in the cases that it might make against prisoners or troopers. I was thrilled to hear this, and soon headed to Albany.

When I got to the museum’s cavernous warehouse, I was glad to be joined by Christine Christopher, a filmmaker making a documentary on Attica with whom I had been working closely. Together we just stood for a while, staring at rows and rows of cartons, boxes, bags, and crates of materials that had been removed from the prison forty years before. And what had been gathered and hidden away for those many decades turned out to be grim indeed. In one particularly mangled container lay a heap of clothing—the dirty, rumpled pants and shirt of a slain correction officer, Carl Valone. His clothing wasn’t soiled merely with decades-old mud from Attica’s D Yard. It was stiff and stained with blood. I had met two of Carl Valone’s kids who were still desperate for answers regarding what, exactly, had happened to their father on September 13, 1971.

And this was just one box. Next to it sat another in which I found the now rigid, blood-soaked clothing of Attica prisoner Elliot “L. D.” Barkley. Like Carl Valone, L. D. Barkley had been gunned down during Attica’s retaking. I had met one of his family members too—L.D.’s younger sister, Traycee. She, like every one of the Valone kids, was also still haunted by Attica.

Although the detritus of Attica that the NYSP had saved in these many boxes revealed little new about why this event played out as it did, it was a harrowing reminder of its human toll. There was a dog-eared red spiral notebook filled with messages written by the prisoners who had survived the retaking, men who had hoped these pages could somehow be smuggled out so that their families and friends might know that they were still alive. There were also cartons of torn and faded photographs of prisoners’ loved ones, countless legal proceedings that the prisoners had painstakingly copied, and even their Bibles and Qurans—all of which had been ripped out of cells in the aftermath of the rebellion.

All of the Attica files that I saw in that dark room of the Erie County courthouse have now vanished, and all of the Attica artifacts that the New York State Museum had been willing to share have also been removed from anyone’s view. But all that I learned from those documents back in 2006 can’t be unlearned, and all of the boxes of bloody Attica clothes and heartbreaking letters written by Attica’s prisoners that I saw back in 2011 can’t be unseen.

And I have decided to include all that I have learned and seen in this book.

That said, this decision was agonizing. Although my job as a historian is to write the past as it was, not as I wished it had been, I have no desire to cause anyone pain in the present. I am well aware, and it haunts me, that my decision to name individuals who have spent the last forty-five years trying to remain unnamed will reopen many old wounds and cause much new suffering. That old wounds were never allowed to heal, and that new suffering is now a certainty, however, is, I believe, the responsibility of officials in the state of New York. It is these officials who have chosen repeatedly, since 1971, to protect the politicians and members of law enforcement who caused so much trauma. It is these officials who could have, and should have, told the whole truth about Attica long ago so that the healing could have begun and Attica’s history would have been just that: history, not present-day politics and pain.

Of course, even this book can’t promise Attica’s survivors the full story. The state of New York still sits on many secrets. This book does vow, however, to recount all that I was able to uncover, and by doing that, at least, perhaps a bit more justice will be done.

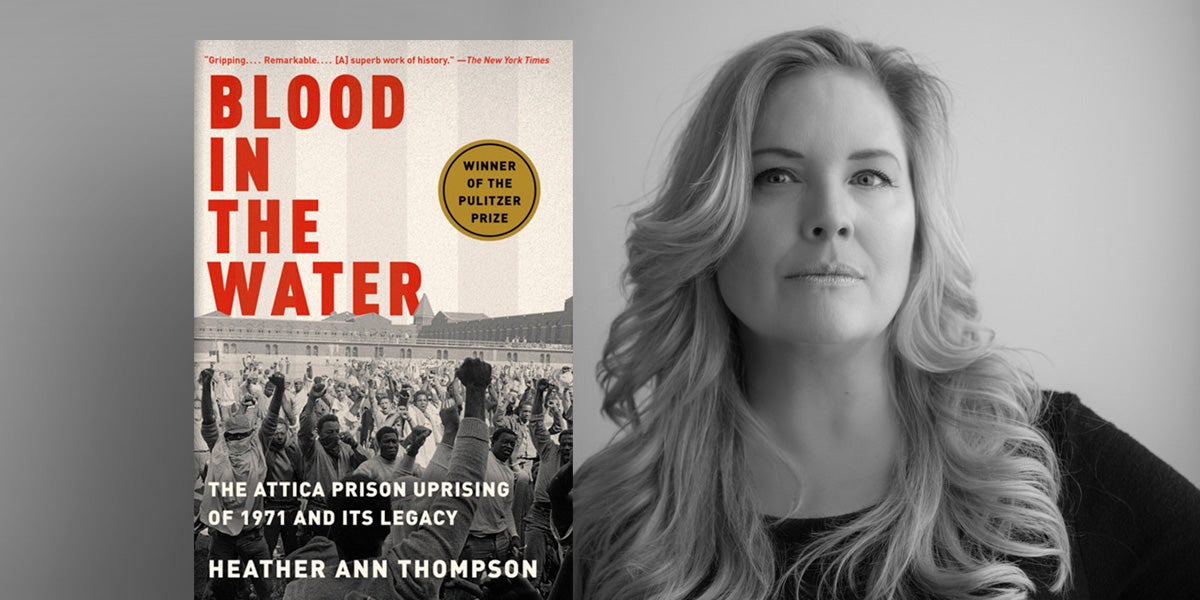

Copyright © 2016 by Heather Ann Thompson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.