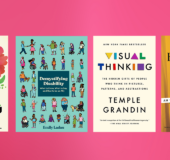

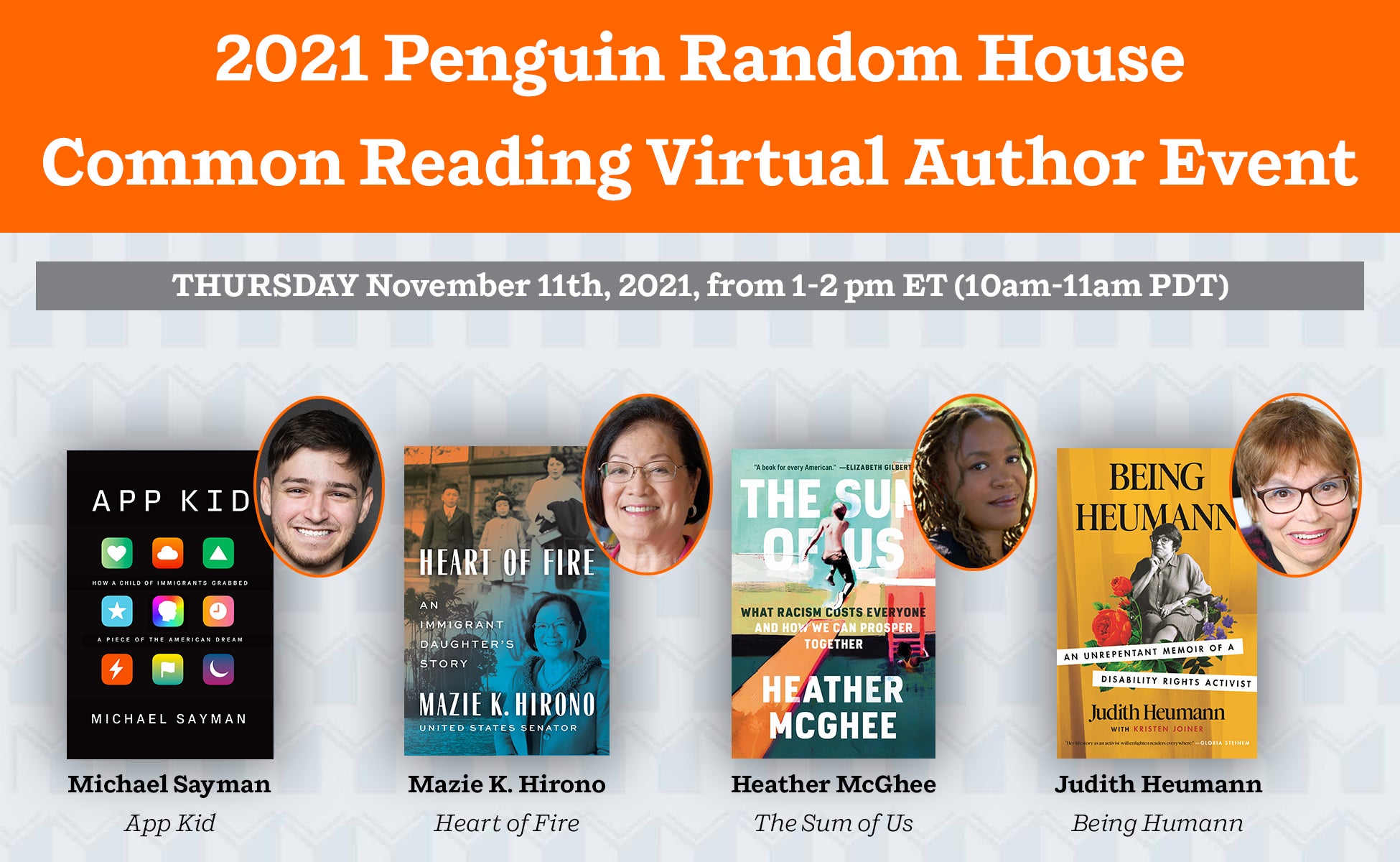

PROLOGUE

I never wished I didn't have a disability.

I’m fairly certain my parents didn’t either. I never asked them, but if I had, I don’t think they would have said that our lives would have been better if I hadn’t had a disability. They accepted it and moved forward. That was who they were. That was their way. They deliberately decided not to tell me what the doctor had advised when I recovered from polio and it became clear I was never going to walk again. It wasn’t until I was in my thirties that I discovered what he’d suggested.“I recommend that you place her in an institution,” he said.

It wasn’t personal. It didn’t have anything to do with our fam-ily being German immigrants. Nor was it ill intentioned. I am sure he sincerely believed that the very best thing for these young parents to do would be to have their two-year-old child raised in an institution.In many ways, institutionalization was the status quo in 1949. Parents weren’t necessarily even encouraged to visit their insti-tutionalized children. Kids with disabilities were considered a hardship, economically and socially. They brought stigma to the family. People thought that when someone in your family had a disability it was because someone had done something wrong.

I don't know how my parents responded to the doctor, because my family didn’t talk a lot about things like this. But I am sure my parents would have found the idea of putting me in an insti-tution very disturbing. Both my mother and my father had been made orphans by the Holocaust. As teenagers they’d been sent to the United States. It was the time when Hitler was coming into power, when things were getting bad enough that people worried about the safety of their children but didn’t think it was going to get as bad as it did. My father came to live with an uncle in Brooklyn at fourteen, and he was lucky that his three brothers followed very soon after. My mother was an only child and was sent alone to live in Chicago with someone she didn’t know at all. The story was that a distant relative came from the States to visit my mother’s family in Germany and brought news of the worsen-ing situation.

The information convinced my grandparents to send my mother, their one child, away to live with this distant relative. I have often imagined what it must have felt like for my mother. You’re twelve years old and one day someone you don’t know, someone you’ve never met before, comes to visit your family and two weeks later you’re suddenly gone from Germany forever, living alone in Chicago with unfamiliar people. My mother always thought that her family would be together again. Even during the war, she was working to save money to bring her parents over. Only later did she learn that they’d been killed. IF I’D BEEN born just ten years earlier and become disabled in Germany, it is almost certain that the German doctor would also have advised that I be institutionalized. The difference is that in-stead of growing up being fed by nurses in a small room with white walls and a roommate, I would have been taken to a special clinic, and at that special clinic, I would have been killed.Before Auschwitz and Dachau, there were institutions where disabled children were eliminated. Hitler’s pilot project for what would ultimately become mass genocide started with disabled children. Doctors encouraged the parents to hand their young children over to specially designated pediatric clinics, where they were either intentionally starved or given a lethal injection.

When the program expanded to include older children, the doctors ex-perimented with gassing.Five thousand children were murdered in these institutions. The Nazis considered people with disabilities a genetic and financial burden on society. Life unworthy of life.So when an authority figure in their new country, a doctor, said to my parents, “We will take your daughter out of your home and raise her,” they never would have agreed to it. They came from a country where families got separated, some children sent away, others taken from their families by the authorities and never returned—all as part of a campaign of systematic dehumanization and murder.Their daughter, disabled or not, wasn’t going anywhere.

MY PARENTS WEREN’T obstinate or antiauthoritarian; they were thinkers. They had learned what happens when hatred and inhu-manity are accepted. Both my father and my mother were brave people who lived by their values. They had personally experi-enced what happens when an entire country chooses not to see something simply because it is not what they wish to see. As a result, they never accepted anything at face value. When some-thing doesn’t feel right, they taught us, you must question it—whether it is an instruction from an authority or what a teacher says in class. At the same time, my parents didn’t dwell on the past or on things that were done to them.They didn’t forget the past, and they definitely learned from it, but Ilse and Werner Heumann moved forward.

Especially Ilse. She was an optimist. And a fighter. And so am I.

I can’t say I was thinking about all these things when we took over the San Francisco Federal Building, or even when I took on the New York City Board of Education. Only now, looking back, can I see how it all came together to turn me into the person I was to become.

Copyright © 2020 by Judith Heumann. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.